In the span of less than ten years, Scottie McNiece and David Allen’s Chicago-based label International Anthem have built a tight-knit musical community around the idea that jazz is a vital and relevant component of contemporary music. “Component” is the key word here: less traditionalists or preservationists than upholders of an evolutionary approach to improvised ensemble music, they’ve taken great pains to both pay proper respect to their predecessors and to build on those predecessors’ principles in a more genre-agnostic sense. Think about the pivotal non-profit musical collective Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians that preceded them in their home turf by fifty years: this was (and remains) an organization that holistically embraced music, art, education, and sociology, all while being committed to finding the new and the transformative, with collective brainstorming and communication honing each individual’s discoveries. Now, where could the inspiration of a precedent like that take a more contemporary musical collective — one that originally started with a couple of punk rockers on the outside looking in?

International Anthem’s magnanimous sense of music-as-community was built in part on McNiece and Allen’s experiences with the DIY grind of live-band recording and touring. Shortly after moving to the city from Bloomington, Indiana in 2009, McNiece had become fascinated by Chicago’s strong yet still comparatively under-the-radar avant-jazz scene, and soon found himself in the fortuitous position to help cultivate a scene he was still in the process of learning about. Working at River North neighborhood establishment Gilt Bar took him on a path from in-house playlist cultivation to booking live acts for the venue’s basement offshoot Curio, and his networking and attraction of artists like Jaimie Branch, Nick Mazzarella, and Rob Mazurek would prove to be enough of a spark to ignite the possibility of starting a label dedicated to a collective vision of improvised music. In December 2012, a weekly stand of shows featuring a trio of cornet player Mazurek, bassist Matt Lux, and drummer Mikel Avery gave McNiece the window to try his hand at recording some sessions, and it was the last one that made the cut; Allen, already an experienced sound engineer, recorded the show to four-track tape. And while it took two years and a Summer 2014 Kickstarter campaign to gain their footing, that show would eventually earn International Anthem’s first catalog number as Alternate Moon Cycles when it dropped that December.

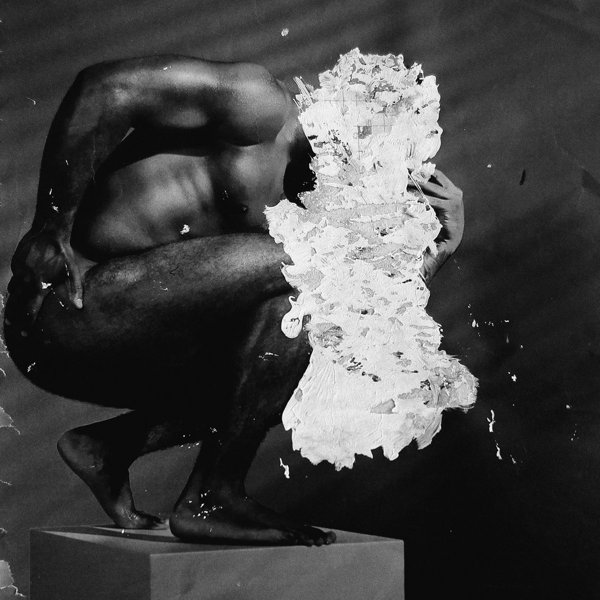

From there, their approach would be simple yet distinct: record sessions by musicians who were connected to avant-garde jazz and improvised music, interfere with the visions of those artists as little as possible, give those releases a bespoke, visual identity-heavy object d’art packaging that added an element of timeless permanence, and adhere to a philosophy that aimed to appeal to listeners who were more curious than intimidated by the idea of “complex” music. It’s that latter element, the belief in a largely younger audience more open to new things than they might otherwise be given credit for, that made International Anthem resonate; that they first planted their feet at a time when both independent record labels and experimental music were both considered untenable money-losing risks only reinforced their art-over-commerce aims.

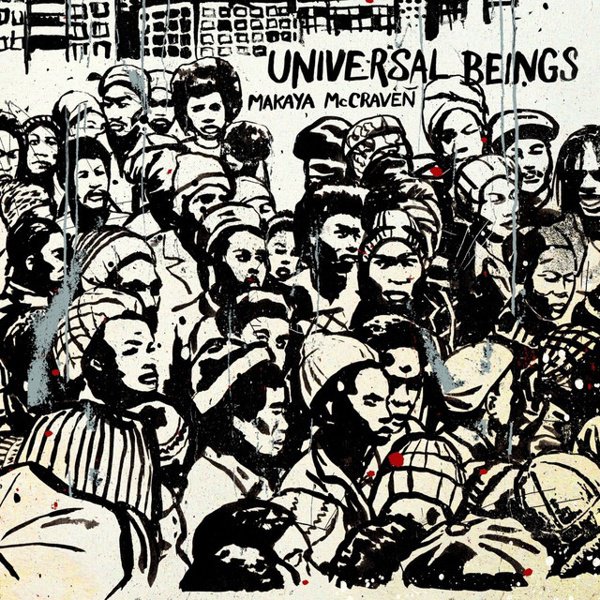

The label-as-family focus not only proved to be a good foundation for International Anthem’s sustainability, it strengthened the local avant-jazz community and fostered the sense of interpersonal collaboration and communication necessary for the kind of exploration they were encouraging. Many of the members of the roster had already found patronage in McNiece’s venue bookings, like drummer/bandleader Makaya McCraven, who honed and refined his more experimental tendencies during a residency at the Bedford in 2013-14, shortly before International Anthem was founded. Those early inspirational recording sessions for Mazurek and McCraven drew further attention from a longstanding figure in the Chicago scene — AACM-affiliated guitarist Jeff Parker, whose membership in Tortoise had made him post-rock royalty and whose occasional participation in McCraven’s Bedford shows provided a powerful co-sign. By the end of 2016 and the release of Parker’s first album for the label, The New Breed, the quality-over-quantity catalog of International Anthem had produced a handful of can’t-miss gems from a small core of artists — just the early wave of a burgeoning scene, but enough to put them in the jazz-revival conversation as a lower-key Midwest counterpart to more established purveyors like Brainfeeder.

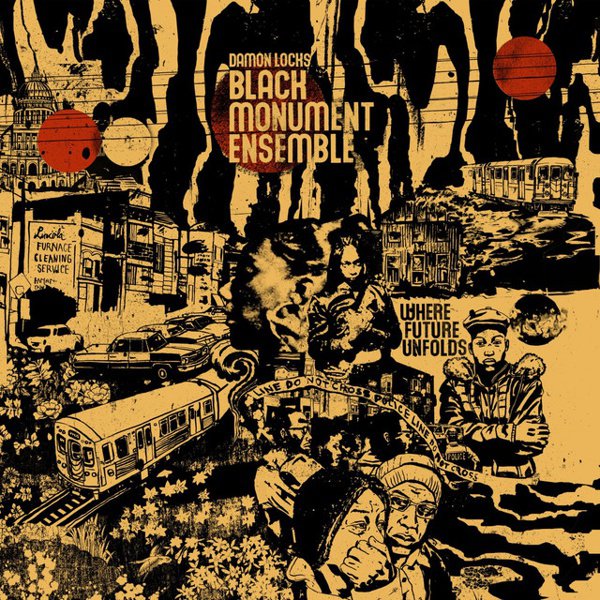

In valuing that particular openness of collaboration as the catalyst for growth, International Anthem found a powerful means to expand their enthusiasms from a DIY “here’s what our cool friends are doing” venture to a thriving indie — one that proves you can still make a living beyond the margins of conventional popular music if you’ve got the right support structure. If their releases have grown more eclectic over time, engaging with improvised music ranging from spiritual and free jazz to ambient electronics and post-psychedelia, that’s by design. After all, you can’t rightly put the word “international” in the name of your label and risk sounding provincial. It’s the sound of Chicago, but there’s plenty of transplants amidst the locals; it’s the sound of contemporary ideas about improvised music, but rooted in the knowledge of previous generations’ groundwork; it’s the dynamics of live-band jazz, but taking that approach in limitless post-genre directions.