Punk was the alarm clock, ending the pop music sleepwalk and complicating the habit of going along for the ride. No argument here—that chair through the window in 1976 was necessary. But what happened next? In many cases, as with the Sex Pistols and the Clash and the Damned, punk turned out to be rock and roll revved up and returned to its original role as unruly dance music. Punk added elements of tone and content, sure, but it was not the antithesis of rock music. Punk was rock music recharged by simplicity and free-floating animus.

So the guitar bands woke up and then what? This is where we get to post-punk, a decent peak for the guitar band. Hip-hop had not transformed popular music fully, and digital tools were years away. Guitar music was in a beautiful interregnum between shifts. There were all these punks standing around, waiting for the next thing. They had taught themselves to play but wanted to do more than pogo and play barre chords. The post-punks had more room for women and dance music and all the weirdos who felt excluded from the vague fascist stomp of punk, liberatory or not. Punk didn’t feel like freedom for everyone, but post-punk kinda did.

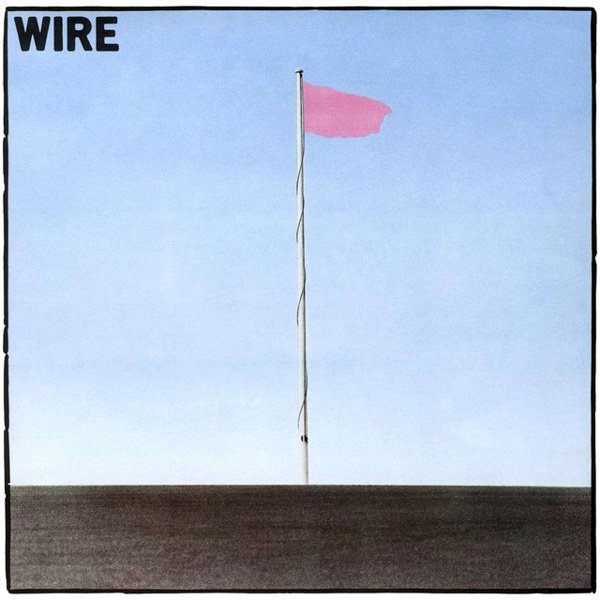

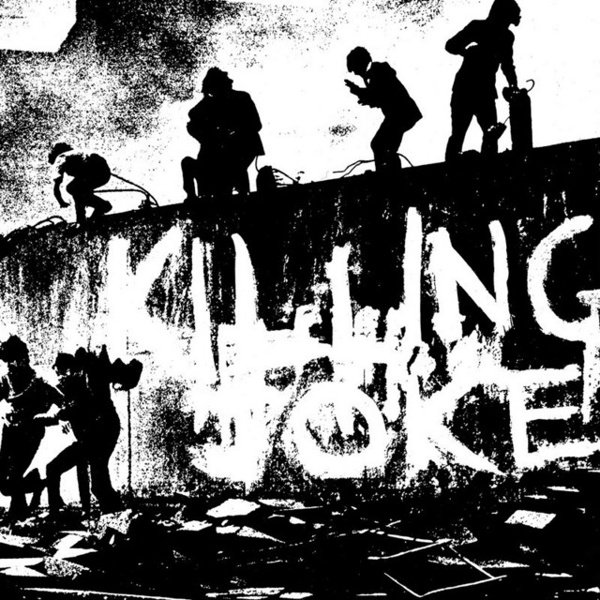

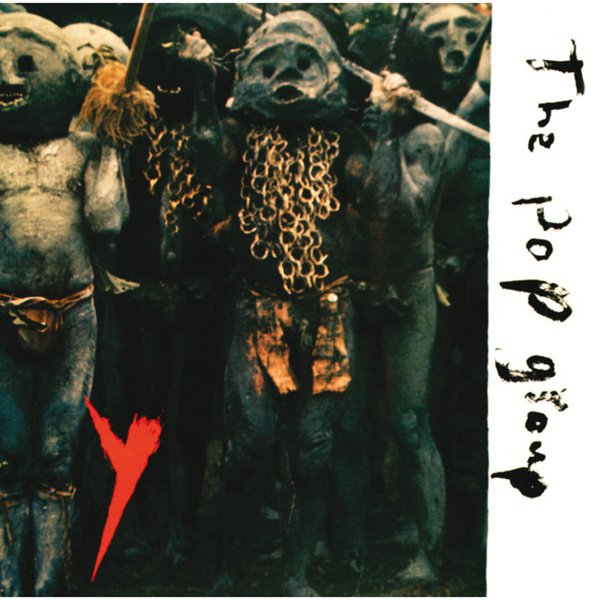

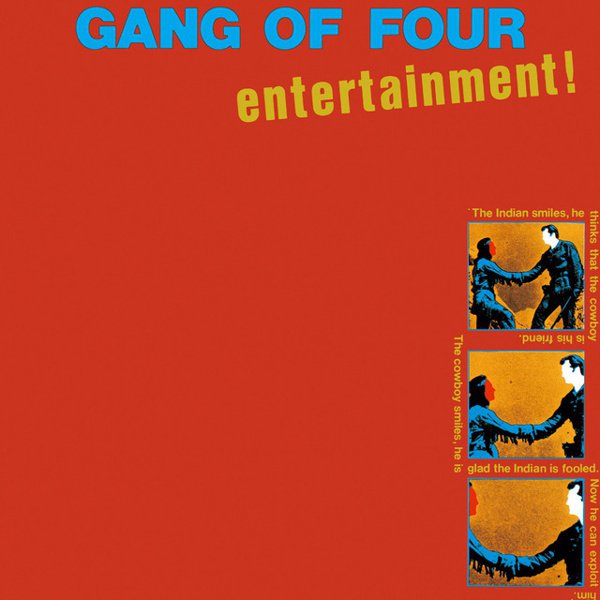

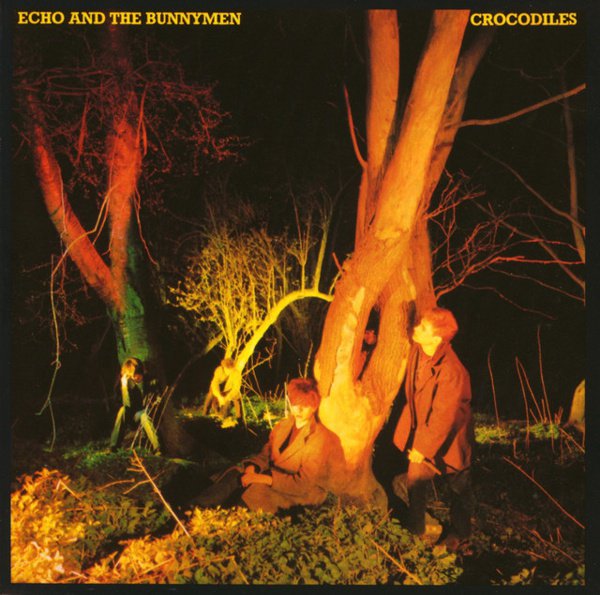

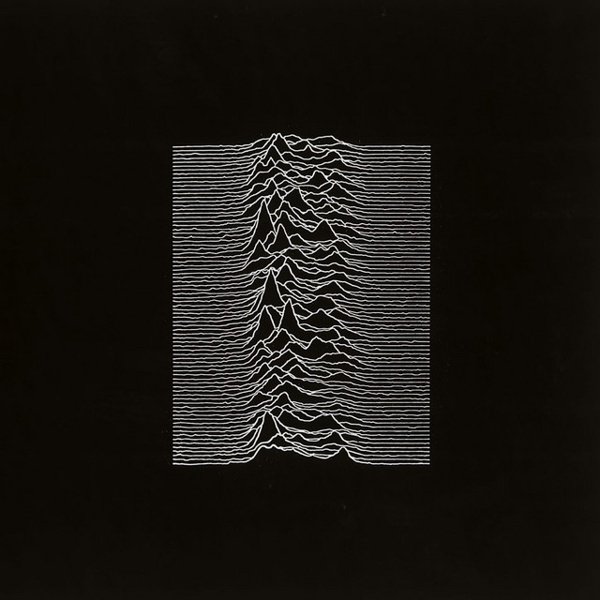

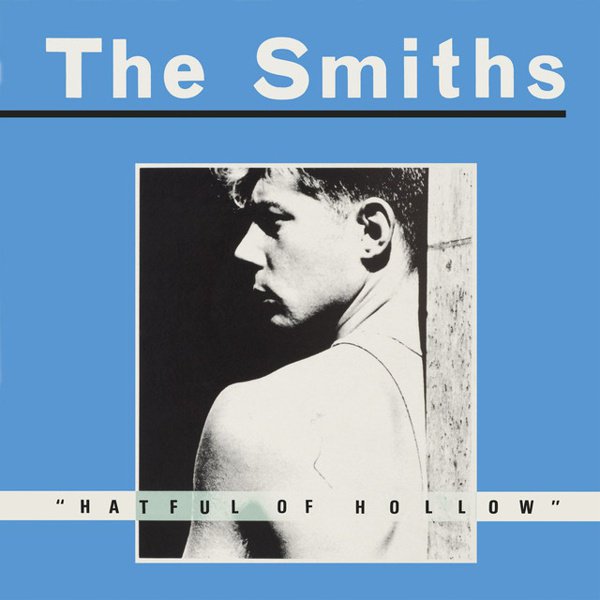

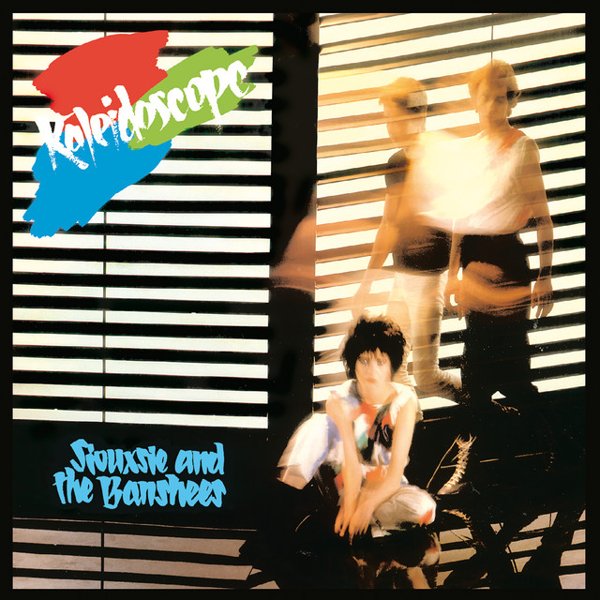

At the level of catalog, post-punk is heavenly stuff. If you had to run away and hide under a tarp with Unknown Pleasures, Entertainment!, Killing Joke, The Scream, and 154, you’d be good for years. The no! of punk was much smaller than the what if? of the post-punk bands. Joy Division started as Stooges fans but then Peter Hook decided to play so high on the neck of his bass it didn’t even sound like a bass and Bernard Sumner refused to play barre chords and Stephen Morris took every beat apart and put it back together with parts missing. And Ian Curtis was his own genre, better than most of the people he imitated. Gang of Four took Dr. Feelgood and James Brown and ran them through a Xerox machine and then traced the shapes and swapped instruments. Siouxsie and the Banshees decided they were in four different bands but didn’t tell each other. Wire pulled off a coup by using the same basic tools as punkety punk bands but managed to sound like the coldest, sweetest, hardest pop band out there when they weren’t sounding like a broken geiger counter. The Smiths, often classed elsewhere, definitely belong here. Where did they get the idea to play short songs voiced like African guitar rock with a soap opera actor moaning over the top? Very post-something.

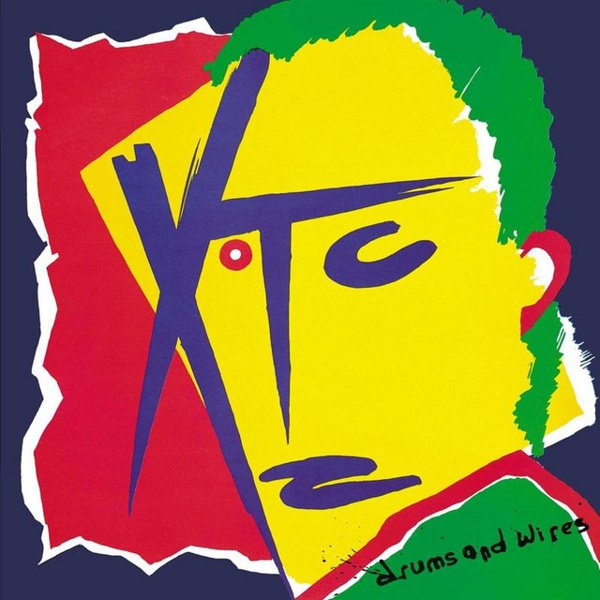

Post-punk was as much a phase as it was anything else. Nobody probably ever said “I’m in a post-punk band” in 1982. (That most likely didn’t happen until 2012.) So a band like XTC, which went through a half dozen stages and ultimately made its bones as a band driven by two pop songwriters, went through some deliciously tortured experiments with drums and wires and sounds and made records that would never have sounded the same twenty years later. Or a week later. What kind of music is “Making Plans For Nigel”? Negative reggae? Backwards rock?

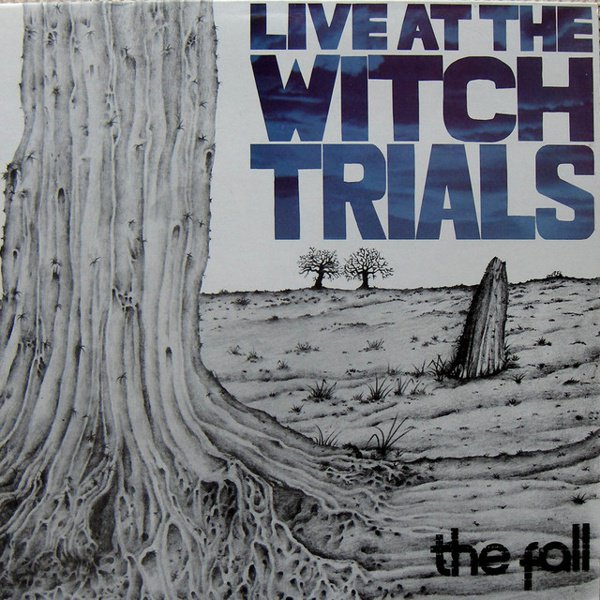

Some bands actually embodied this make your own style approach forever. The Fall are somehow a completely rock rock band while being nothing of the sort. Is that the spirit of the age? Mark E. Smith has no corollary or imitator worth mentioning. The Fall songs all go on slightly too long or have a sound that doesn’t quite fit. The idea that a sound could maybe not lead anywhere at all, not to popularity, not to collaboration, but only back to itself, was central to the post-punk moment.

If a term like “post-punk,” applied from the outside, unlike jungle or hardcore, terms introduced by the artists, is going to mean anything, it helps to focus on the time frame (where the post- points to) and structural signposts. What post-punk came to mean, by the nineties, is the presence of trebly, percussive guitar parts and a rhythm section that played something other than a straight back beat. The singer is a little shouty. If you can find a record store, and they have a section named post-punk, that will be what you find.

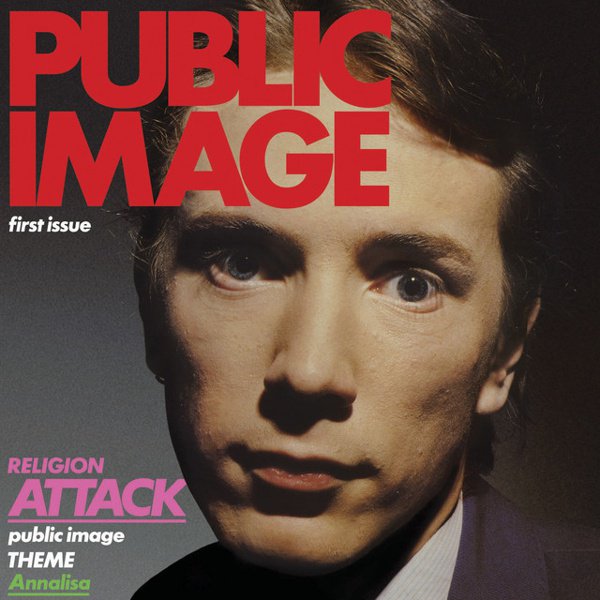

But the most post- bands of all didn’t sound like that. If you want to clear out your preconceived notions, look to three bands: Public Image Ltd., The Raincoats, and Killing Joke. PiL were coming out of the most famous punk band of all time, your Sex Pistols. And their first single, “Public Image,” was an A+ rock song, absolutely a prime example of guitar music with words you can understand, a vehicle for John Lydon to complain about everybody looking at him after asking everybody to look at him. Their second album, though, was more upsetting to rock fellas than anything the Pistols ever did. Second Edition is over-discussed and overrated and isn’t much more than a bunch of jam sessions edited into reasonable shape. It’s also insanely important and mostly great.

Three things happen that make Second Edition so much a thing that people can’t stop talking about. One, Jah Wobble’s bass is louder than everything else. The Clash were lifting reggae, but PiL were lifting reggae strategies without playing it. Lydon, as complex a figure as rock has ever produced, had an early gimlet eye on appropriation and had no intention of playing cod reggae, while also knowing exactly what had to be done. Second, the songs are not in any recognizable verse/chorus shape. Things happen for a while and then they stop, which would be the format of dance music for the next twenty or thirty years. Third, it just sounds strange as hell. Keith Levene’s guitar seems to be pointed into a corner and EQ’d with no clear goal. Irritation? Lydon is, slightly counter-intuitively, the star of the show. His singing on “Poptones” alone is a whole new world. Someone has dragged him into the forest to shoot him in the head? But he’s still alive? Is the music playing on the cassette PiL or Depeche Mode? But ha—that wasn’t the absolutely most post-punk ass album ever. No!

For my imaginary money, Flowers of Romance is not necessarily the best post-punk album (we don’t do that kind of thing around here) but holy frappuccino, it is definitely one of the most intransigent albums ever put out on Warner Brothers’ dime, and that includes all the Beefheart. You’d think that the band would suffer without Wobble—on the contrary. Without bass, the band somehow rose up into stratospherically beautiful wrongness. Hell, there’s barely any guitar. This is drumming and yelling, as far from Chuck Berry as you can get before you’re just trying to break your lease. Drummer Martin Atkins tries to pound his set into the fourth dimension and Lydon sings as if he is trying to raise the dead in three time zones. Most of the music doesn’t even qualify as songs or rock or really anything that anybody would ever play intentionally or sell tickets to. It’s a loopy bag of rebar and someone will ask you to take it off if you put it on. Also—if you wanted another name for post-punk, you could do worse than Martin Atkins.

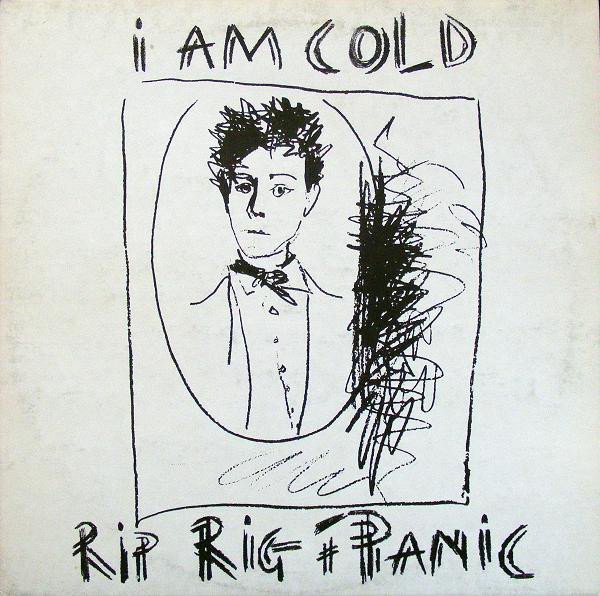

Some of that refusenik chaos was also in The Pop Group and Rip, Rig + Panic, two different bands that were comrades to dub and jazz without ever really fitting in. That lunging, unembarrassed quality was one of the best aspects of post-punk—you couldn’t really do it wrong, and that spirit was valuable. On the other side of the earth, Nick Cave and The Birthday Party channeled all of this unsupervised energy and recorded some of the best un-rock rock ever, all of the contempt and tongue-on-battery house arrest masochism with none of the normal. Release the bats? Honey, they’re long gone!

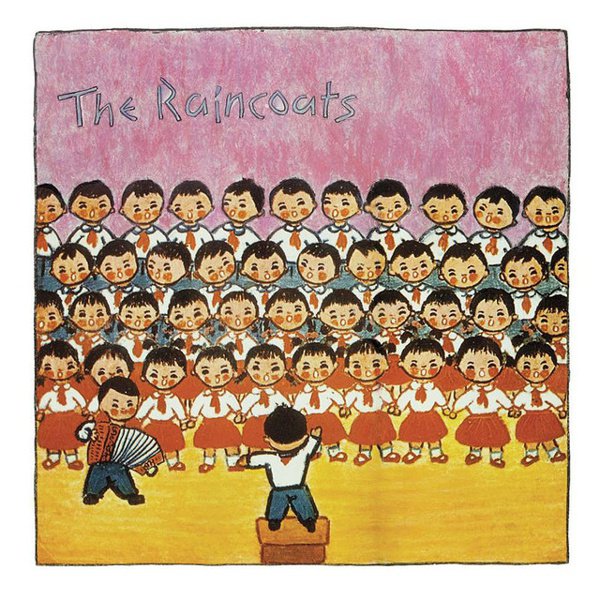

At the other end, post-punk had room for gentleness and quiet, and some attributes that would eventually be recycled into the twee side of American indie. The first time around, though, this was unbiddable weirdness. The Raincoats were like ghosts wandering the streets of London, scaring the shit out of anybody looking for a copy of Smash Hits. Listening to the violin on “Shouting Out Loud”—nothing reassuring about these women and their energy. And where post-punk met the wider world was in dance music, which was about to transform Manchester, the seat of much post-punk. The first song that made clear that this was the future was The Normal’s “Warm Leatherette” (1978), which was as avant-garde as it was danceable. The band that became infinitely bigger after what seemed like a career ending was New Order, more or less a dance band from day one until the present.

The record to close with, to make the loop, is my favorite album in this entire clump. (OK, so I lied.) Killing Joke’s 1980 debut is, song for song, one of the most consequential albums ever released. “Requiem”? An entire genre of scary synth rock that probably had a hand in half the goth out there. “Change”? A dance single that by his own admission, inspired a chunk of James Murphy’s work in LCD Soundsystem. “The Wait”? Inspiration for at least a third of Metallica’s sound, and they won’t tell you any different. (Look up their cover on Garage Days Revisited.) There were dance remixes of Killing Joke songs from day one, as well as dub versions. The original disco punks, Killing Joke have never been made redundant and their work suggests, again and again, that the investigations of the post-punk era will remain relevant long beyond that moment.