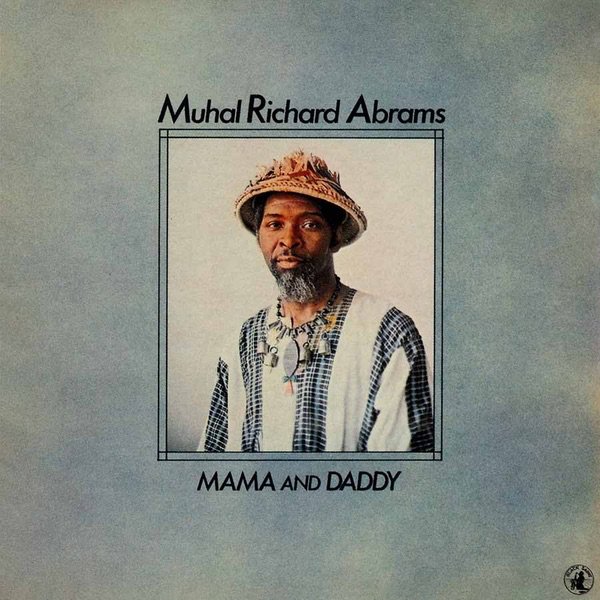

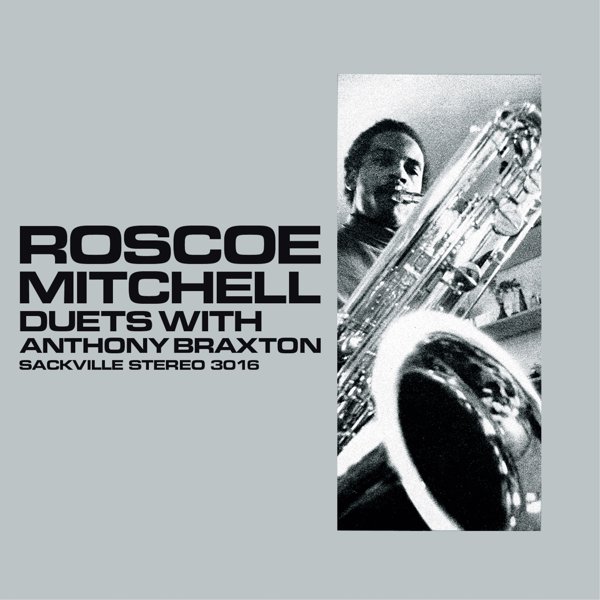

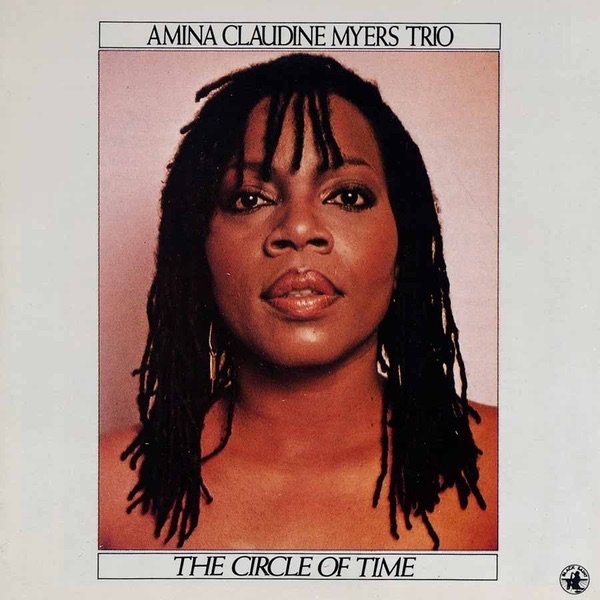

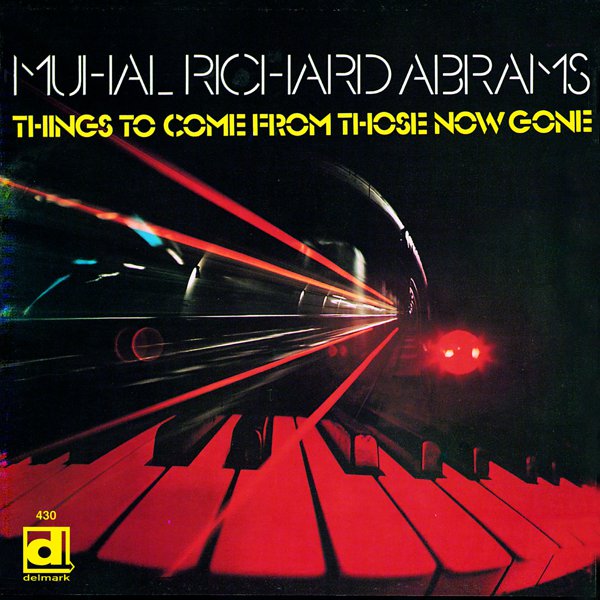

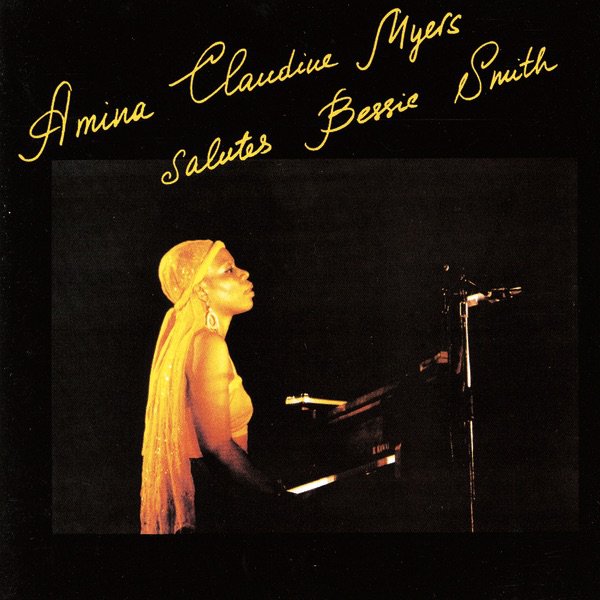

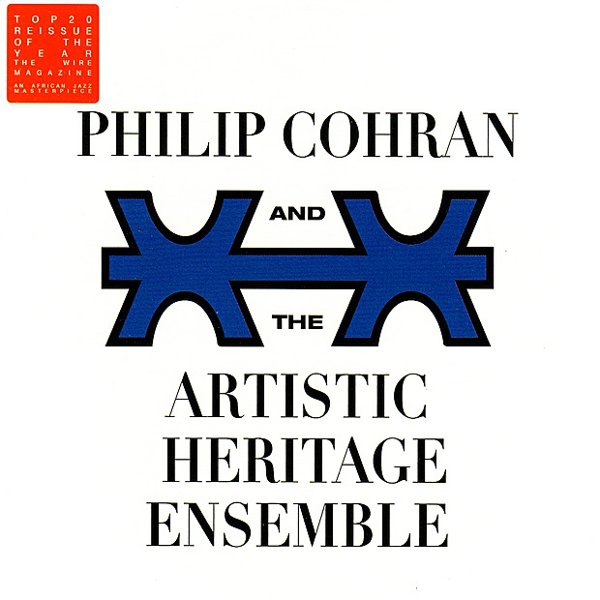

The Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians is one of the most important musical organizations in American history, and likely world history. Founded in 1965 by pianist Muhal Richard Abrams, brass player Philip Cohran, pianist Jodie Christian and percussionist Steve McCall, its ranks quickly swelled to include saxophonists Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman, Fred Anderson, Anthony Braxton, and Henry Threadgill; trumpeters Wadada Leo Smith and Lester Bowie; pianist Amina Claudine Myers; drummer Jack DeJohnette; violinist Leroy Jenkins; and many others. With its emphasis on collective effort and mutual support, its insistence that its members compose their own new music, and its focus on education — they started their own music school — the organization reshaped avant-garde jazz in its own image.

Abrams, born in 1930, had been cutting his own musical path since the 1950s; in 1962, influenced by the compositional theories of Joseph Schillinger, he began organizing workshops full of players younger than himself, which eventually became known as the Experimental Band. The core principles of the Experimental Band, which never recorded anything for release and rarely performed before the public, were very similar to those which would eventually animate the AACM: cooperation, exchange of knowledge, and the playing of original music. The AACM was also an explicitly Black organization, which sought to circumvent the exploitation of the jazz club scene by booking their own performances.

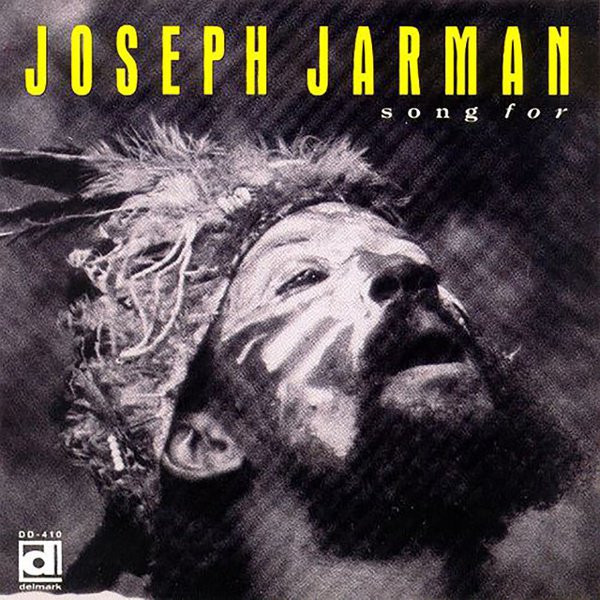

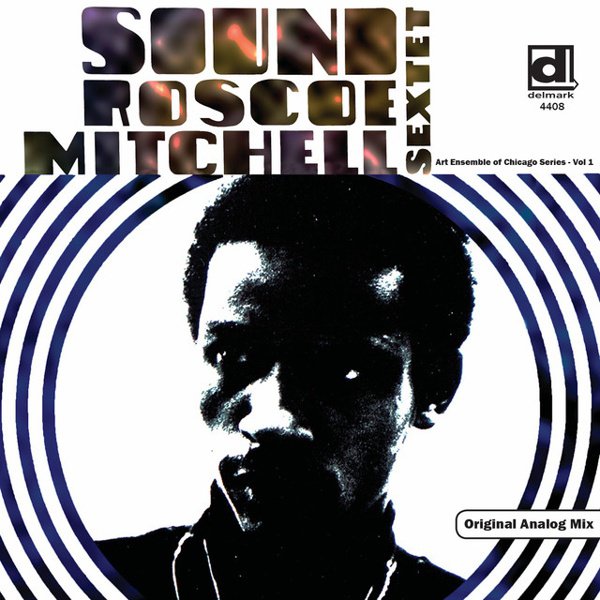

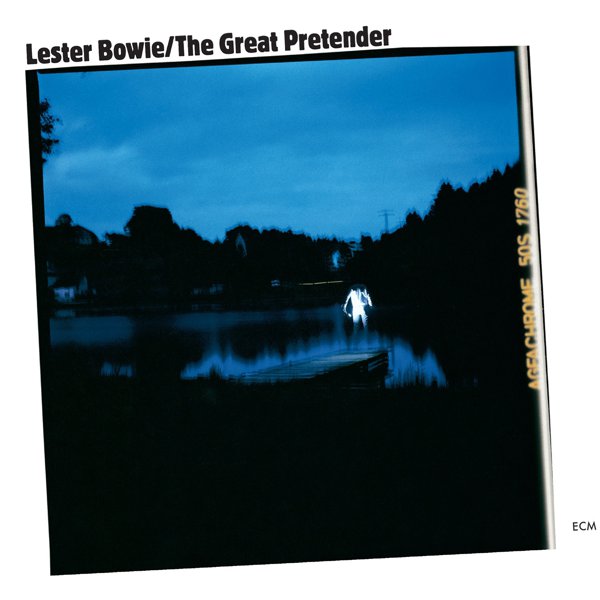

Two Chicago-based independent labels were crucial to getting the word out about the AACM: Delmark, a blues and hard bop imprint, and Nessa, run by Chuck Nessa, a Delmark employee. Between 1966 and 1968, Delmark released Roscoe Mitchell’s Sound, Joseph Jarman’s Song For, Abrams’ Levels and Degrees of Light, and Anthony Braxton’s 3 Compositions of New Jazz. Nessa, meanwhile, released Lester Bowie’s Numbers 1 & 2 and Mitchell’s Congliptious and Old/Quartet, in the process laying the foundations for the formation of the Art Ensemble of Chicago.

The Art Ensemble’s arrival in Paris in the summer of 1969, with Braxton, Jenkins, and Smith following close behind, took the AACM international, and they created a sensation within the European avant-garde. In 1971, Braxton made a major statement with For Alto, a double LP of unaccompanied solo saxophone improvisations — the first jazz album in that format.

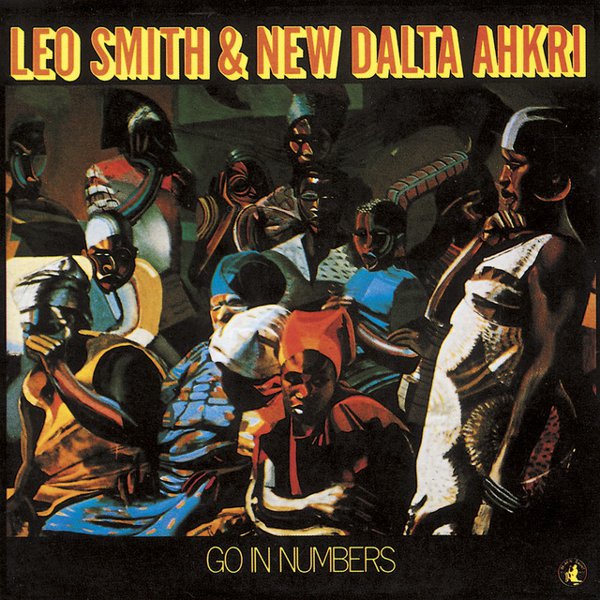

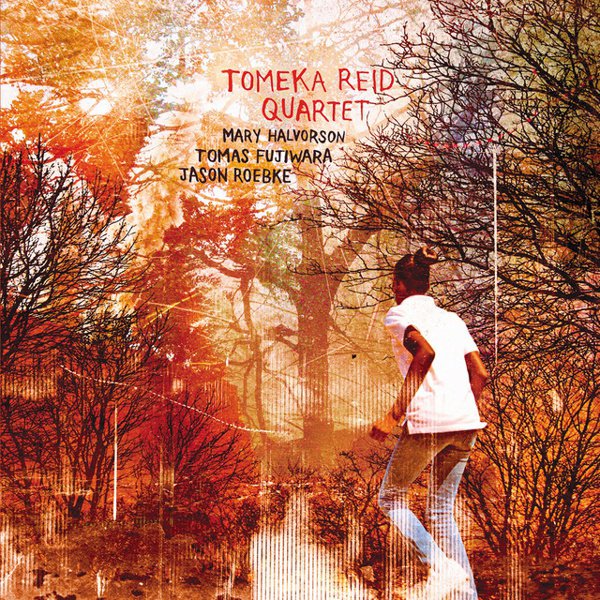

The 1970s were a fertile period for AACM artists, as Braxton, the Art Ensemble, Smith, and Henry Threadgill (first with Air, then as a leader) all rose to prominence, many departing Chicago for New York and the loft jazz scene (see separate guide). A New York branch of the AACM put on its first concerts in 1982, and still exists today. Even as the jazz market as a whole shrank in the ’80s and ’90s, the principles that they had so carefully cultivated bore fruit in the form of new generations of players bent on continuing the organization’s work. Fred Anderson’s Velvet Lounge bar became a key gathering place for the Chicago jazz scene, and players like alto saxophonist Matana Roberts, flutist Nicole Mitchell (who became the AACM’s first female chair in 2009), percussionist Kahil El’Zabar, and others injected new blood into the music. Now, players like cellist Tomeka Reid, bassist Junius Paul, and drummer Mike Reed represent the 21st century face of the AACM, even as the surviving elders like Mitchell, Smith, and Art Ensemble percussionist Famoudou Don Moye keep the original flame burning.