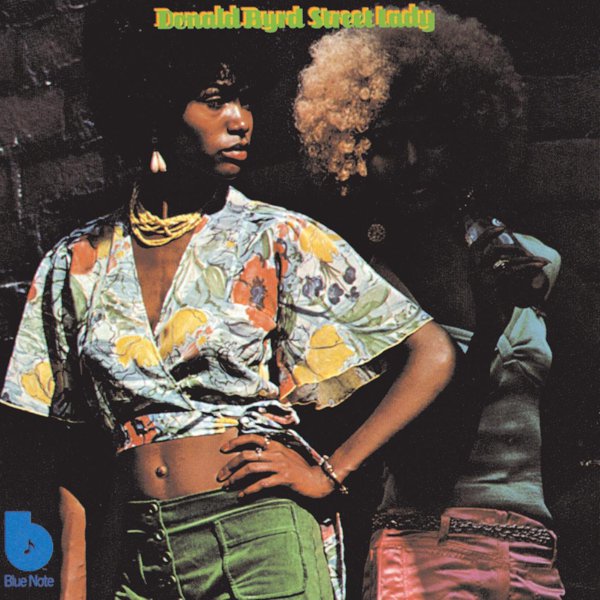

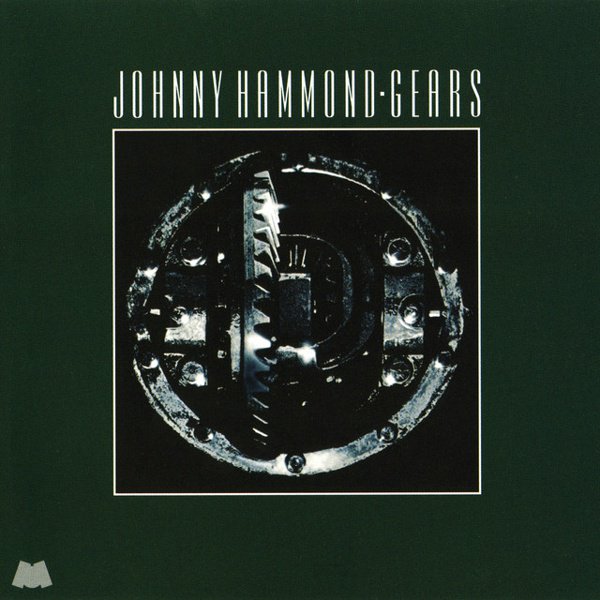

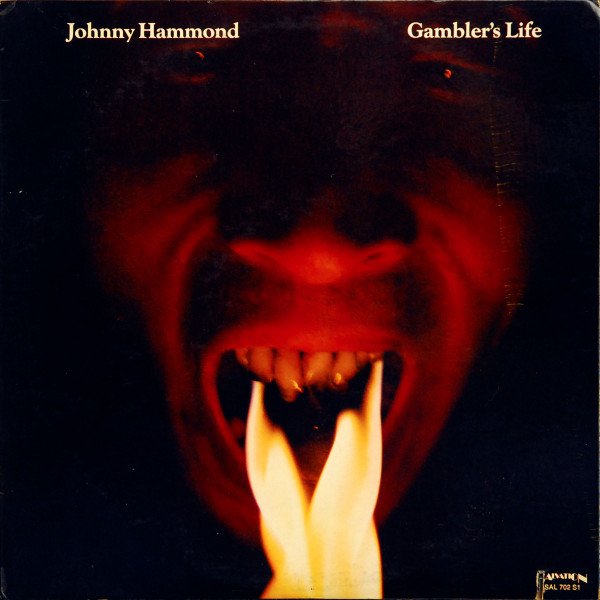

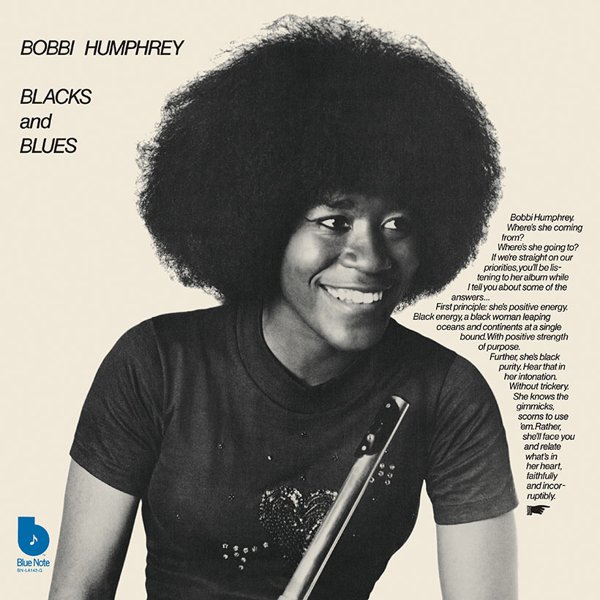

It’s rare for a production unit to have such a small discography in such a short period of time and yet be so recognizably integral to a musical movement that it’s impossible to imagine their absence. Larry and Alphonso Mizell belong in that rarefied category, right up near the top, for their contributions to a corner of crossover music that took longer than it should have to earn its due respect. Sure, it might have taken a surprise wave of hip-hop producers and acid jazz enthusiasts to catch on and appreciate it in the face of purist naysaying, with at least 15 years’ distance after the Mizells’ brief but indelible moment in the sun. But when it came time to give the ’70s fusion era of jazz greats like Donald Byrd, Bobbie Humphrey, and Johnny Hammond their cross-generational propers, heads knew that Larry and Fonce were names to appreciate.

Both siblings were already steeped in music by the time they graduated Howard University — even if it was Fonce who got his degree in music, while kid brother Larry studied engineering. (Some musicians dream of doing an Apollo gig; in Larry’s case, this initially meant building, testing and troubleshooting electrical systems for NASA’s Lunar Module in the late ’60s.) Music would eventually prove to be the bigger calling for both siblings, as something of a familial destiny — great-uncle Andy Razaf was an early Tin Pan Alley songwriter and frequent collaborator of Fats Waller, while they had cousins who would become genre-defining legends in both girl-group pop (The Ronettes) and hip-hop (Run-D.M.C.’s DJ Jam Master Jay).

After a bit of trial-and-error, Fonce got his own foot in the music-biz door in the most fortuitous way possible, getting hired by Motown and joining Berry Gordy’s new record production unit The Corporation — just in time to contribute writing and arrangement to the songs that would make the Jackson 5 one of the biggest sensations in pop music. Once the Corporation split in 1972, Fonce convinced Larry to ditch the aerospace business to join him out in Cali to start a new operation, Sky High Productions, that carried through the brothers’ experience of working with R&B musicians into new territory. They’d both caught on to how Motown had swapped out the old blues for something more intangibly modern, a blend of technological innovation, compositional daring, and jazz-chops musicianship, and went out for themselves to see where else this inspiration could take them.

Fatefully, they landed at Blue Note and cut their first sessions for the label in Spring of 1972, right as the movement towards integrating funk, soul, and rock into jazz was leaving the stalwart label in flux. Under the leadership of recently-appointed executive George Butler, Blue Note’s turn towards more commercial records was threatening to alienate an aging base of jazz traditionalists. But the Mizell Brothers’ productions — despite often being laden with string sections, ARP synthesizers, and the brothers’ own relatively flat yet appealingly warm vocal harmonies — still clearly valued chops and improvisation that built off rock-solid rhythmic foundations. And in doing so, they cemented a recurring core of session players, including bassists Chuck Rainey and Wilton Felder, drummer Harvey Mason, guitarists “Wah Wah” Watson and David T. Walker, percussionist King Errisson, and synth player/Corporation alumni Freddie Perren, who ranked among the great undersung architects of ’70s funk, soul, and disco.

The Mizells would notch classics for Blue Note, Milestone, CTI, and a host of other jazz labels before eventually receding from prominence in the ’80s. And when it all clicked, which was most of the time, the vibes were immaculate. Listening to a Mizells-helmed album is to be greeted with the same kind of energy that made R&B of the day so opulent and experimental and thrilling, just in the service of a jazz tradition that was in search of an elusive continued relevance. If that meant putting out records that sounded a little more like Johnnie Taylor than Cecil Taylor, so be it. But that soul-pop accessibility, especially in retrospect, comes across like the culmination of an almost intensely euphoric sense of musical joy, the expression of a certain hard-earned mellowness that felt like the optimist approach to coping with the era’s lingering turmoil.

![Hell Up in Harlem [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5674138202013696_600.jpg)