Here’s a funny thing about the Neptunes: for a group who ushered synthesized future-funk production through the last days of the recording industry’s bottomless-budget era, they sound remarkably minimalist. Consider the precedents and successors in their lineage, the digital-minded producers who wrung maximalist depth out of simplicity: compared to the cyberfunk Roland/Ensoniq gearheadedness of the Jam/Lewis ’80s and the Nicktoonish full-spectrum glitch overload of recent SOPHIE-and-scions hyperpop, Chad and Pharrell’s jams sound borderline austere.

But that’s one of the rare examples of austerity actually working for the masses, the simplicity of the idea that you need a Beat and you need a Hook and everything else is an asterisk. Why build a wall of sound when a patio door makes for more light and easier accessibility? And so they took over the world, at least for an unrelentingly transformative half-decade on the charts (and a fair amount of time afterwards), with their choppy-rolling symphonies to negative space sounding more punk-funk — or at least new [and] wavy — than Rick James’s wildest dreams.

Back in MC Hammer times, Pharrell Williams used to hang out with Virginia Beach buddies Timbaland and Magoo making boom-bap-goes-pop beats under the snarkily named collective Surrounded By Idiots. Turns out he’d surrounded himself with geniuses. He’d started working with Chad Hugo by the time the Neptunes-to-be found themselves under the aegis of Teddy Riley, right about the same time that Mary J. Blige’s What’s the 411? popularized hip-hop production tropes for mainstream R&B. (One month after that album dropped, the Riley-produced Wreckx-n-Effect hip-hop crossover classic “Rump Shaker” gave Pharrell his first big-hit writing credit on a major hit record, though his contributions were strictly lyrical.)

But it was the Neptunes’ ’98 breakout, riding off a two-fer of hip-hop crossover hits for Ma$e (“Lookin’ At Me”) and Noreaga (“Superthug”), that made their trademark musical identity both immediately identifiable and provably successful. In part it’s because their musical components were so counterintuitively weird, building off the simplicity of the Korg Triton synthesizer and finding all the off-kilter ways they could break its limitations. Throughout the late ’90s and early 2000s, the Neptunes made a barrage of hits out of twangy/plinky synth hooks that pinged somewhere between guitar and harpsichord, rhythmic programming so crisp and tight and frictionless that their low-reverb impacts hit like a one-inch punch, and melodies that simultaneously vibed off celebratory invincibility and unresolved tension. Even Pharrell’s own voice, an askew falsetto like Curtis Mayfield trying to hold in a toke, sounded just disorientingly odd enough to make circa-2000 hits like Jay-Z’s “I Just Wanna Love U (Give It 2 Me)” and Mystikal’s “Shake Ya Ass” seem at least a bit alien.

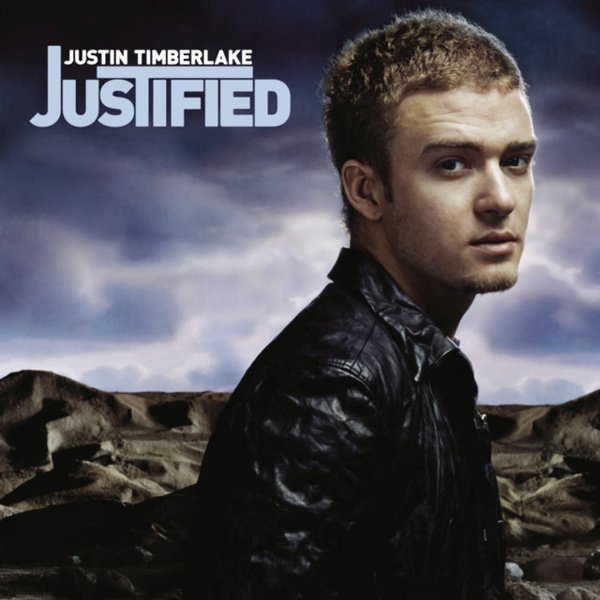

Another reason The Neptunes so capably took over music is that their ascent, already co-signed by hip-hop and R&B’s most pop-savvy kingmakers, hit right when mainstream pop was in its first truly massive reckoning with the dominance of that crossover potential. When TRL-bred surname-unnecessary icons like Britney and Justin turned towards the Neptunes, it meant that not only were these performers looking to tap into a sound that was a bit more outlandish than their usual Euro-pop Max Martin machinery, it meant they were engaging with a hip-hop-rooted sound as a way to push themselves further into more innovative creative contexts.

That’s a big burden, having that much chart-busting weight resting on your sound — but it was a sound that proved as effective as it was omnipresent, whether you were into hardcore hip-hop (Fabolous’s “Young’n (Holla Back)”), rap’s pop-friendler club jams (Nelly’s “Hot In Herre”), or its Soulquarian/bohemian strains (Common’s “Come Close”). Expand that to cover top-shelf dancehall (Beenie Man’s Janet Jackson duet “Feel It Boy”), teen-pop maturation efforts (NSYNC’s “Girlfriend”), and VIP room R&B (Usher’s “U Don’t Have to Call”), and you’ve got a stylistic versatility that defied repetition or formula. And that’s just 2002, one year in an early-decade stretch so soaked with their presence that “43% of songs played on American radio in 2003 were Neptunes productions” became a widely-believed (if completely apocryphal) pseudostatistic. Even accounting for their gradual taper-off in hit-factory hyperproductivity that began around 2004, you could pull up a playlist of well over 800 songs Chad and/or Pharrell had a hand in and still find yourself wondering “yeah, but is that everything they did?”

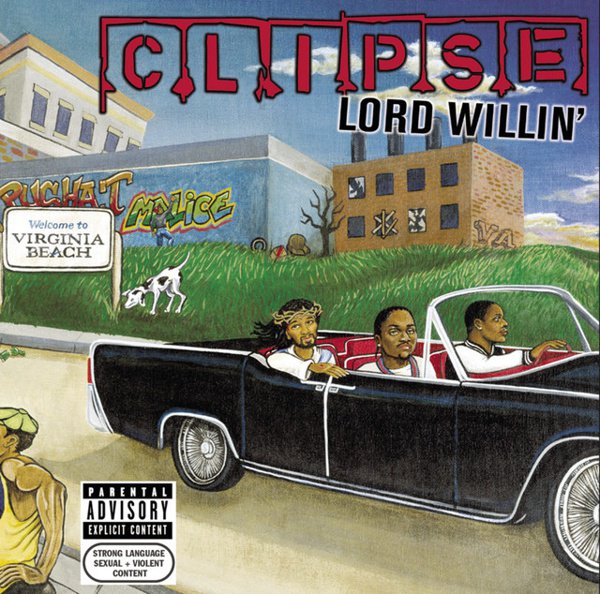

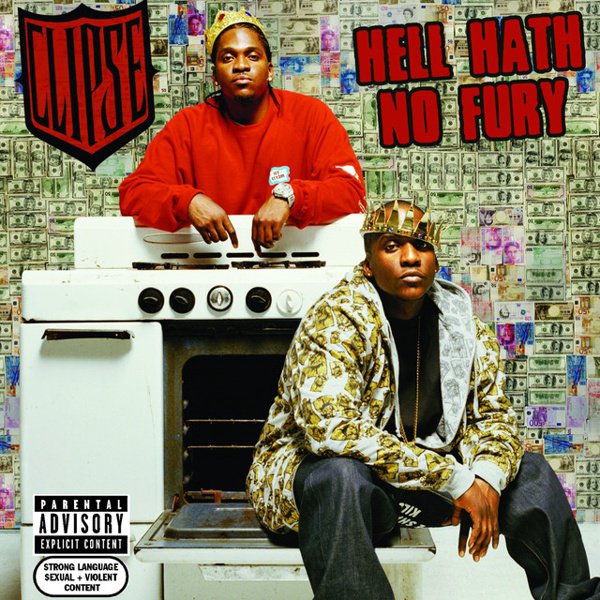

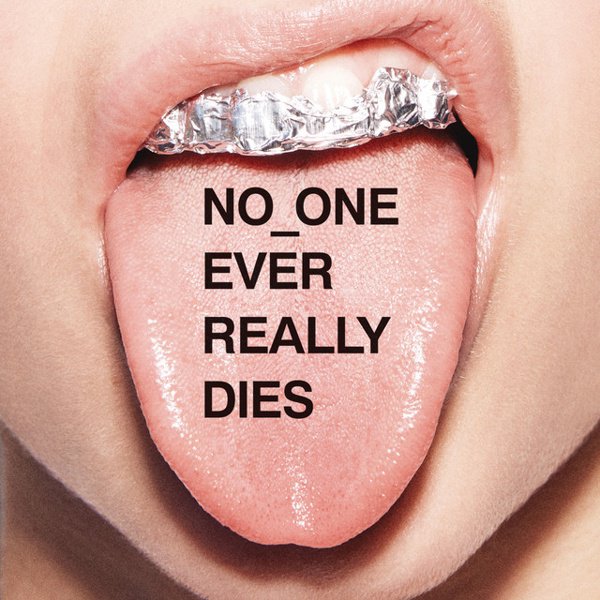

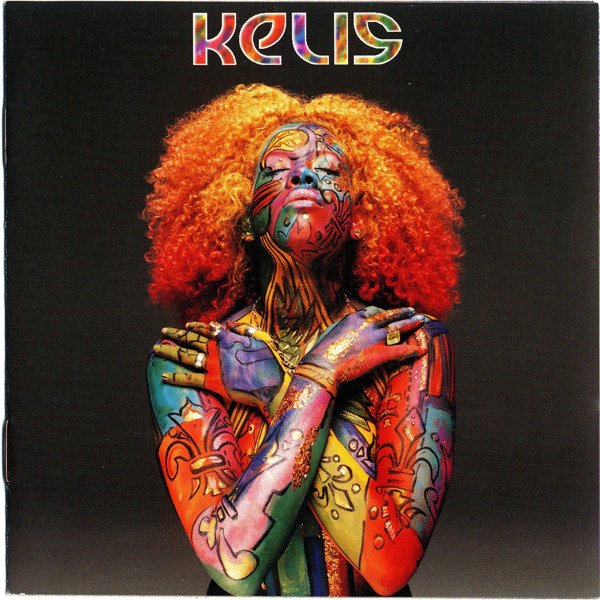

Here’s another funny thing about the Neptunes: their story’s borne out best in their individual tracks, and this guide is largely album-driven, so we’re looking at them from a sort of obtuse angle. Full-lengths where they actually handled most or even more than half of the production duties are surprisingly rare, and ones that are front-to-back great taper off after the mid 2000s (apologies to Snoop Dogg’s Bush and Madonna’s Hard Candy). But that just reveals another facet to the Neptunes that speaks to a necessary restlessness beneath the surface of their dominance. Their ability to spread so much wealth while still remaining loyal to a core of collaborators they’d practically drop everything to work with — particularly their hometown coke-rap dons Clipse and pop’n’B-mutating singer Kelis — offset the mercenary-for-everyone ubiquity that would’ve ground down less-insightful producers. That ubiquity receded after half a decade, leading to an increasingly sporadic but still curious and readily-engaged elder statesmen status, even if much of it was overshadowed by Pharrell’s sole-billed efforts beginning with the double whammy of “Blurred Lines” and “Happy” in 2013. But just ask Odd Future — or anyone else who came of age when Pharrell and Chad seemed like the biggest thing since the LinnDrum: no sound ever really dies.