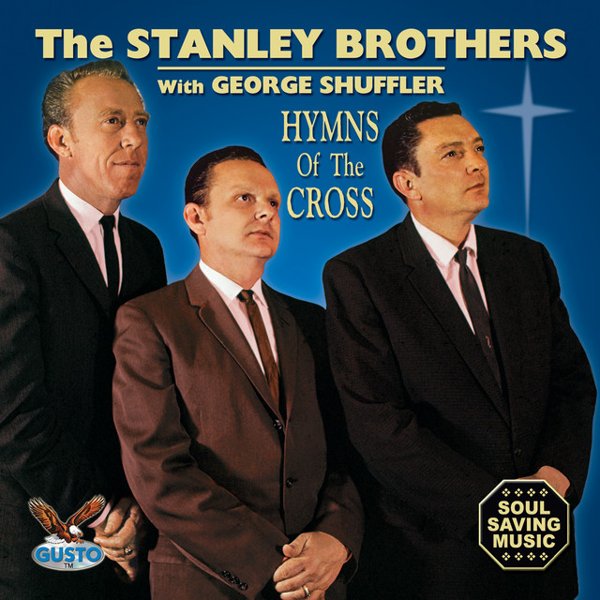

Bluegrass is a form of commercial country music that developed in America’s Appalachian region in the middle of the 20th century, emerging as a mature and fully-developed style in the mid-1940s. It has its roots in several different musical antecedents, the two most important being the traditional songs and fiddle tunes of the British Isles that were brought to that mountain region by Scottish and Irish immigrants in the 19th century, and Black gospel and blues styles. Both of these traditions feature a rhythmic emphasis on the backbeat, as well as a highly emotional vocal delivery and idiosyncratic uses of harmonic modes and note ornamentation, all of which can still be heard in traditional bluegrass music.

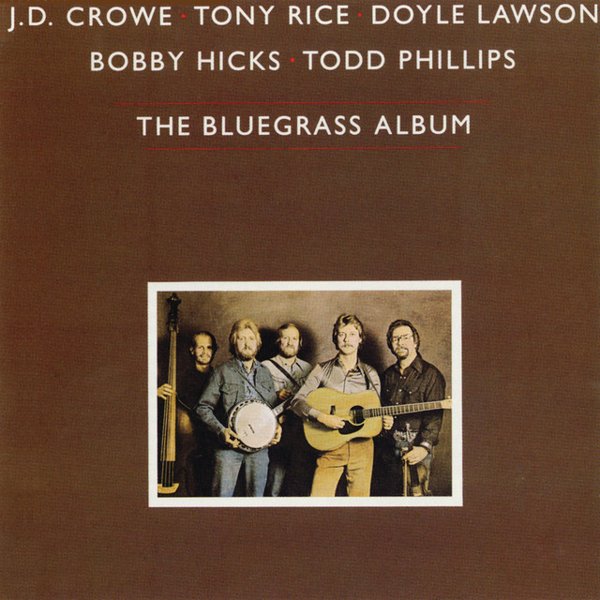

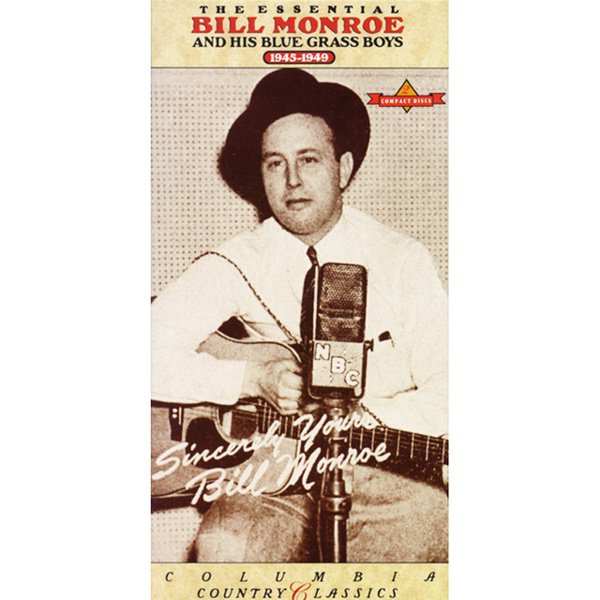

Bluegrass is one of the few musical forms to have been named after an artist: the term derives from Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys, who are credited with having largely created and ultimately perfected the music’s instrumental, vocal, and stage conventions. In the 1930s, before forming his own band, Monroe had performed as a duo with his brother Charlie in what was then the popular “brother duet” format: Charlie sang lead and played guitar, while Bill sang high tenor harmonies and played mandolin. The tenor-singing mandolin player would eventually become a standard feature of the typical bluegrass band, which would also usually include a lead-singing guitarist, a banjo player (in the “three-finger” or “Scruggs” style, named after Monroe’s banjo player Earl Scruggs), a fiddler, and an upright bass player. In the early years, Monroe’s band also included an accordion player, but the accordion quickly fell out of favor as a bluegrass instrument, while the resophonic guitar became a common feature in the 1950s.

Traditional bluegrass performance has quite a bit in common structurally with jazz. While vocal numbers are typically performed in a manner similar to that of pop music (verse-chorus song structures with instrumental solos between verses), instrumental performances follow the same approach as that of straight-ahead jazz: the band (or some subset of it) plays a tune, each member takes a turn playing an improvised solo based on the tune, the band plays the tune itself again, and the song ends. Instrumental virtuosity is highly valued among bluegrass musicians, and is largely expressed in these solos; vocal skill – and especially the ability to sing in harmony – is also important, but less crucial than the ability to pick with speed and creativity.

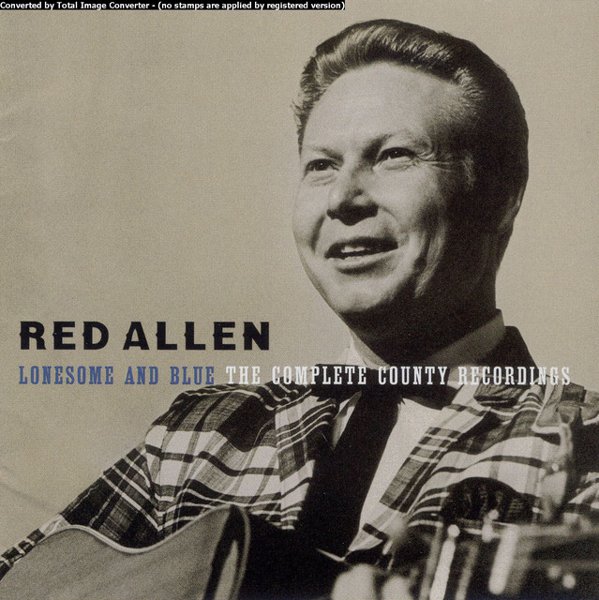

Bill Monroe’s group was the launching pad for what is generally considered to be the second greatest bluegrass band of all time: the Foggy Mountain Boys, led by guitarist/singer Lester Flatt and banjo player Earl Scruggs. Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs were both alumni of the Blue Grass Boys, but left to expand their musical horizons. In the 1960s they provided soundtrack music for both the highly popular Beverly Hillbillies TV show and the film Bonnie and Clyde, bringing bluegrass music to a nationwide audience for the first time. Flatt’s voice was smoother and deeper than Monroe’s “high lonesome” tenor, and lended itself to more commercial musical stylings; after his success, a new generation of bluegrass singers began taking the music in a somewhat more mainstream direction.

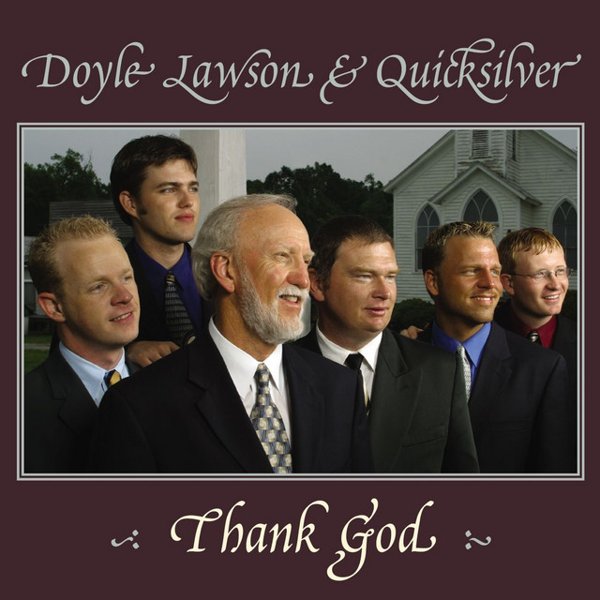

In the 80 years since it first emerged, bluegrass music has spawned multiple subgenres and variants, but there continues to be a solid core of fans who prefer the hard-edged mountain sound of traditional bluegrass, and a small but dependable cohort of artists who still perform and record in that vein.