Some revolutions combust, violent as a powder keg, while other revolutions are more like a decades-long wick: a subtle, slow-moving subversion that sometimes takes decades to fully develop and detonate. The US-backed military coup that ousted Brazilian President João Goulart in 1964, taking control of all branches of government and bringing an end to democracy there for more than two decades, is an example of the former. In history books, the date given for that particular revolution is March 31, 1964, though singer-songwriter Caetano Veloso insists that the tanks rolled out the next day, i.e. on April Fool’s Day.

Veloso was part of the latter type of revolution, Tropicália. Under the dark, oppressive shadows of the junta and its attendant repressive policies, tropicálists focused instead on arts-poetry-music-film, providing a brief glint of light amid the “vazio cultural” (cultural void) or “the suffocation” that followed after the coup. It was a revolution in sound that took decades to rise up from Brazil and spread around the world. Tropicália took its name from an art installation of the same name, originally conceived by visual artist Hélio Oiticica in 1967. It was a revolutionary piece of art delivered with the slyest of winks. Viewers walked into a pop-up structure meant to look like a favela, strolling along a tropical sand path filled with fake palm fronds and plastic chairs, only to come face-to-face with a television set in the sand. Was this paradise? Or was paradise yet another mass-market consumable? (That piece might have been coy enough to escape government censorship, but Oiticica’s 1968 piece seja marginal, seja herói, featuring an image of a bandit gunned down in the favela by the police, made him a subject of intense scrutiny and he left for New York City for many years.)

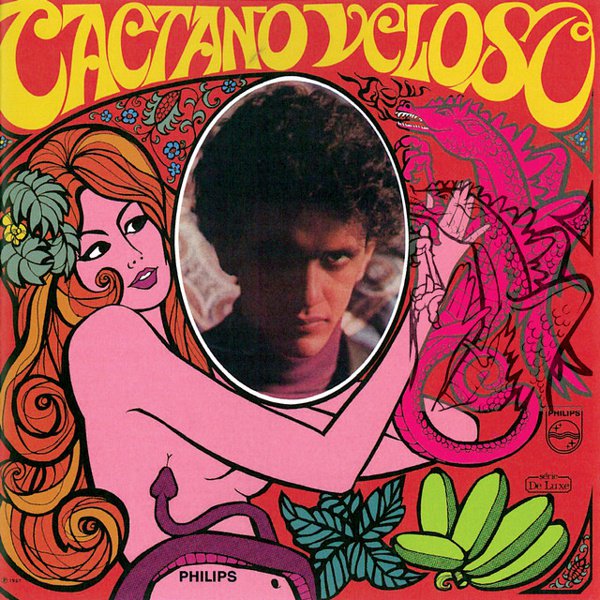

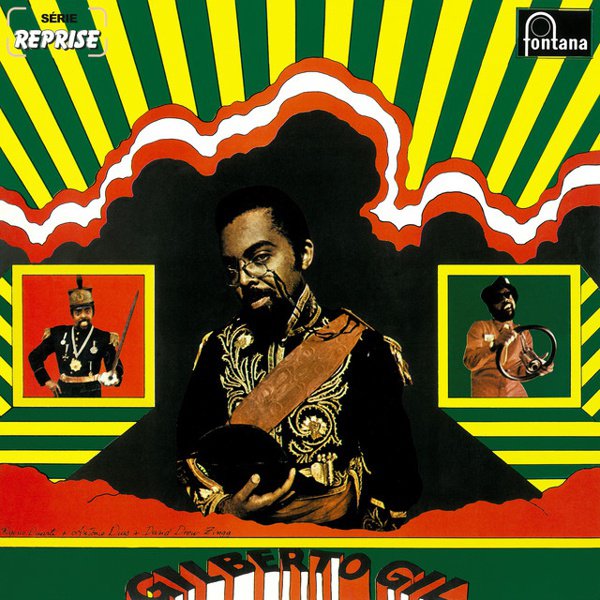

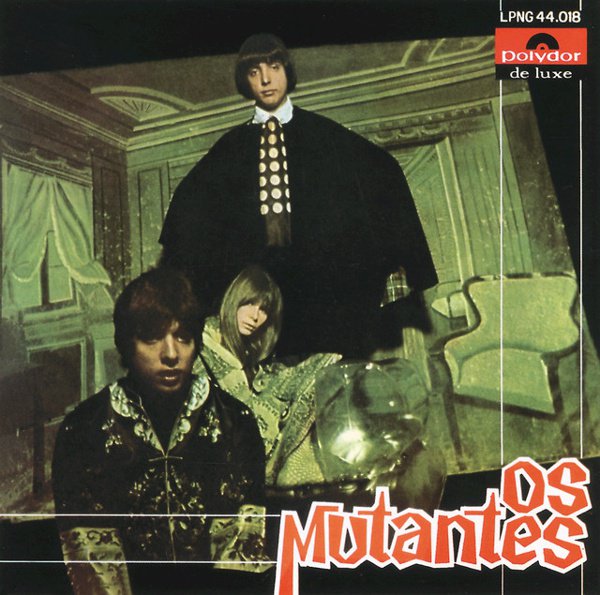

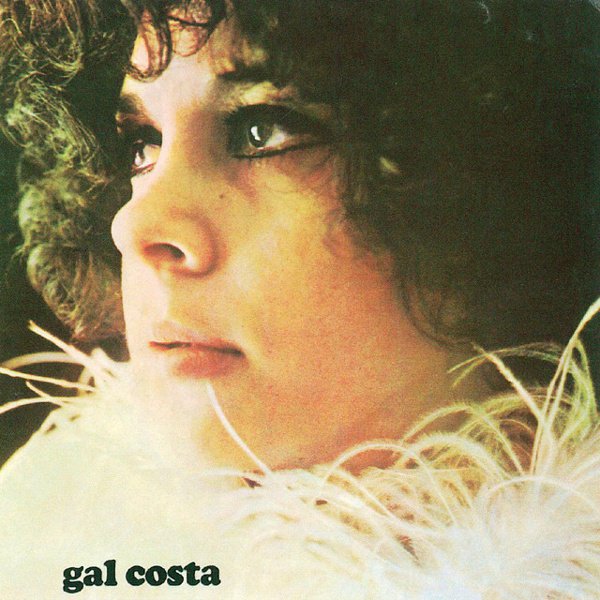

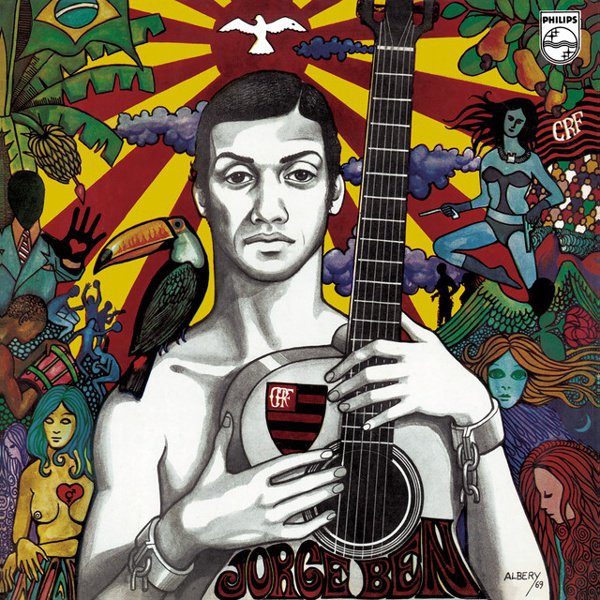

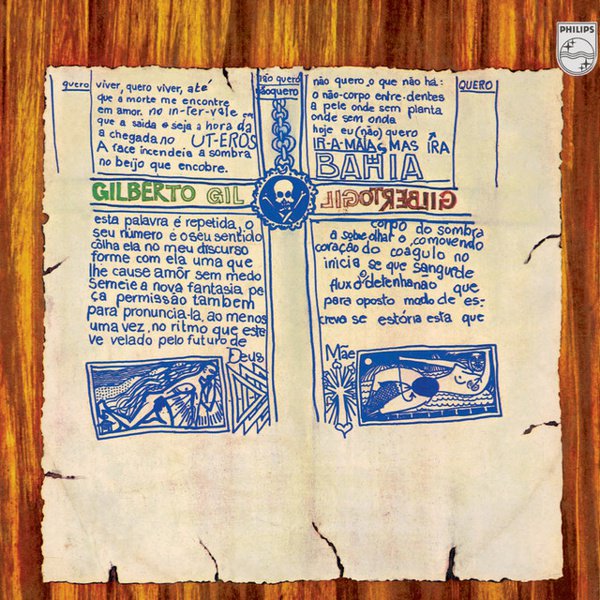

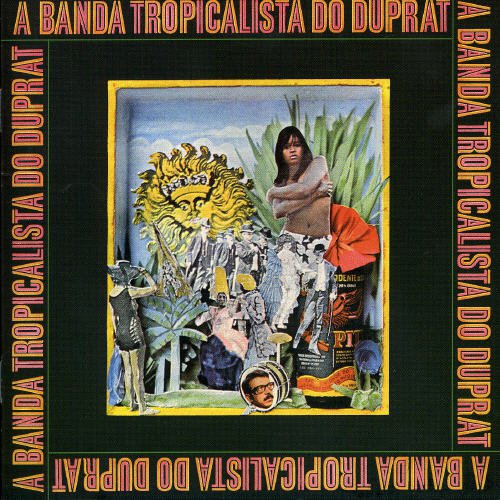

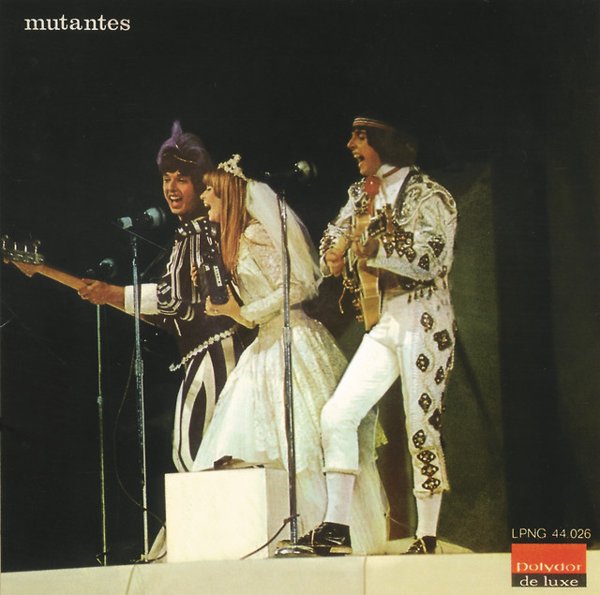

Veloso and a band of similarly brash and inspired musicians – including Gilberto Gil, Os Mutantes, Gal Costa, Nara Leão, Tom Zé, arranger Rogério Duprat, guitar hero Lanny, and others – courted unbridled glee and controversy in equal measure. They genuflected before the refined sound of their country’s finest musical export, bossa nova, and gobbled it up alongside the wooliest psychedelia imports coming from overseas. They loved concrete poetry and Pop art. They adored Brigitte Bardot as much as they did Carmen Miranda. Cue up any of the albums that fall under the heading of Tropicália and they brim with joy, unfettered sound, infinite possibility. “The idea of cultural cannibalism fit Tropicalistas like a glove; we were ‘eating’ the Beatles and Jimi Hendrix,” Veloso wrote in his book Tropical Truth about that era. “We wanted to participate in the worldwide language both to strengthen ourselves as a people and to affirm our originality.”

Tropicálist artists, flippant, fun, and mischievous as their music was, were instead perceived as threats by both sides of their country’s political spectrum. The Marxist left considered them apolitical, obsessed with superfluous Western pop music rather than traditional Brazilian sounds. And to the fascist right, such playfulness scanned as anarchy, a real threat to the country’s status quo. And even though Tropicália itself burned away in less than a year (fittingly, it was given an on-air burial ceremony), its reverberations were long-lasting.

Tropicália produced only a handful of proper albums and a compilation of the same name, but it went on to transform Música Popular Brasileira (MPB) and to inspire future generations from Brazil and around the world. As author Christopher Dunn put it in Brutality Garden, his 2001 book on the movement, this was “simultaneously an exciting period of counter cultural experimentation and severe political repression.”

Not long after the televised burial of Tropicália in 1968, the military government issued a highly restrictive decree called AI-5 (Institutional Act Number Five). The legislation shuttered the National Congress, imposed strict censorship on media, and suspended habeas corpus. Meanwhile, extralegal police forces began to patrol the city streets. They were renowned for their sadism, and – according to Brasil: Nunca Mais, a report published in 1985 that reckoned with the dictatorship’s torture record – they were funded “by contributions from various multinational corporations, including Ford and General Motors.”

Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine describes disposed Brazilian president Goulart as “an economic nationalist committed to land redistribution, higher salaries, and a daring plan to force foreign multinationals to reinvest a percentage of their profits back into the Brazilian economy,” a plan that was decidedly at odds with the paranoiac anti-communism of the US at the time. Privatization of natural resources and public services, coupled with cutbacks to social programs, was the prescription of the day, implemented through the Southern Hemisphere by other US-approved leaders like Jorge Videla in Argentina and General Augusto Pinochet in Chile (whose soldiers infamously tortured and murdered outspoken singer Víctor Jara and displayed his corpse outside the entrance to Chile Stadium as a warning).

Early one morning, Veloso and Gil woke up to the police at their doors. They were arrested without charges, imprisoned for months, later placed under house arrest, and only released after agreeing to leave the country. With its two main figureheads gone, Tropicália as a movement drifted apart. Os Mutantes turned from their impish early sound to heavier progressive rock riffs. Gal Costa became one of the country’s most beloved MPB superstars, and Tom Zé carried on with his own itchy, irascible deconstructions of native musical forms.

Some enjoyed stardom and success, others teetered on the brink of obscurity, and in 1972 Veloso and Gil returned to Brazil and resumed their careers there. But all felt the deep freeze as the military regime’s reign stretched to decades. Few outside of the Southern Hemisphere heard such music until the 1990s brought about a renaissance.

David Byrne’s Luaka Bop imprint reissued a compilation of Tom Zé’s music in 1990 and one highlighting Os Mutantes in 1999. Nirvana famously tried to get Os Mutantes to reform for a Brazilian tour in 1993. Beck, Nelly Furtado, and Panda Bear have all been vocal about their love for this music. Tropicália might not have toppled the dictatorship on the strength of a few guitar chords, but that was never its sole purpose. As Veloso argues in his book: “Tropicalismo wanted to project itself as the triumph over two notions: one, that the version of the Western enterprise offered by American pop and mass culture was potentially liberating… and two, the horrifying humiliation represented by capitulation to the narrow interests of dominant groups, whether at home or internationally.” That indomitable spirit remains vibrant and vital well into the 21st century, where a new round of regressive regimes have emerged both in Brazil and in many countries around the world.

![Caetano Veloso [1969] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5157204036681728_v1_600.jpg)

![Gal Costa [Cinema Olympia] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5449842750914560_600.jpg)