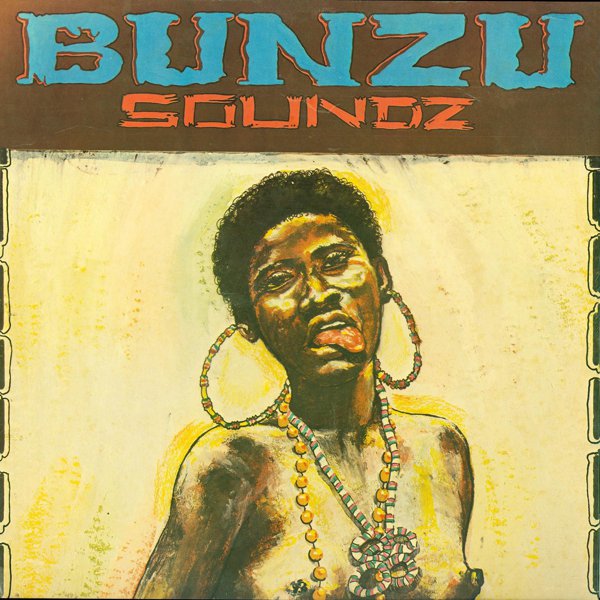

Akwaaba: Music for Sanza

Few musicians – no matter the continent – were as prolific and diligent as Cameroon’s Francis Bebey. Bebey penned novels, poems, plays, and short stories, worked as a radio broadcaster while also collecting folk tales and writing books about African music as a folklorist. And he recorded over two dozen albums during his lifetime, utilizing acoustic guitar, mbira, the ndehu (a one-note bamboo flute created by the Central African pygmies), as well as synthesizers and drum machines. None of his albums are as joyous and noisy as his 1984 album, Akwaaba: Music For Sanza. Accompanying himself on mbira and ndehu, these jaunty songs also feature his double-tracked growling voice, building up layers to mesmerizing effect.

Decades before Konono Nº1 hit the stage with their electrified likembés (also known as sanza or thumb pianos) Cameroonian writer and multi instrumentals Francis Bebey had already produced an entire album based on his electronically modified sanza. The 1985 Akwaaba: Music For Sanza represents a significant jump forward for Bebey compared to his earlier electronic experimentations of the mid 1970s. Rather than limiting himself to playing traditional instruments alongside modern technologies, he pays more attention to how all the different elements interact with each other, weaving extended, psychedelic tracks that get up to almost 10 minutes long. His delicate sanza playing is obviously the focus of the record, interwoven with bass guitar, drum machine, and n’deho, and although many of the tracks are completely instrumental, he gets the most experimental with his vocals, heavily distorting his voice on tracks such as “Bissau”, or using his breathing and high-pitched tones almost as an instrument on “Sassandra.” In a 1982 interview with Chris May, Bebey said that it was imperative “that the future of African music be based on the idea of development and not merely upon preservation,” and that incorporating different influences into African music would give rise to a “new form of Black African Art.” Over forty years later, it’s safe to say that he was right, and that he played no small part in making it so.