Recommended by

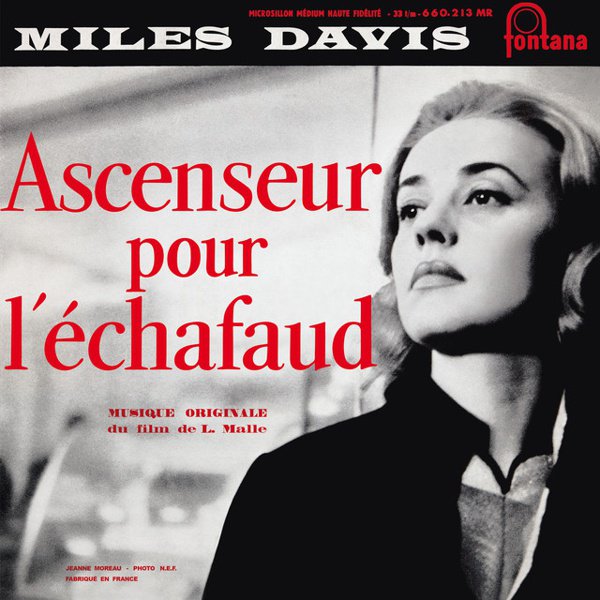

Ascenseur Pour L'Échafaud

Kind of Blue and Milestones may have earned all the sales and acclaim, but at some point the retrospective view of Miles Davis’s late ’50s work grew to appreciate this 1958 Louis Malle film score on a comparable level — and not just because it seemed to fit a certain ideal of “noir jazz” and its connection to cinematic cool. Released as a 10” EP/mini-LP in France and given its own LP side for the 1959 compilation Jazz Track, Davis’s music for Ascenseur Pour L’Echafaud was recorded with no real recurring themes or even a pre-composed score, just a few chord progressions he’d worked up after the screening and gave to the group of Parisian musicians he’d been touring Europe with to improvise around. (Early Miles Davis Quintet drummer and ex-pat Kenny Clarke was one of them, joined by Barney Wilen on sax, René Urtreger on piano, and Pierre Michelot on bass.) Its improvised spontaneity came through Miles’ emerging developments in adapting modal jazz’s scales-over-chords priority to his own ends, those ends being an ensemble performance featuring some of his most distinctly melancholy and even harrowing melodic forays. Opening theme “Générique” might as well be the standard at which all evocative doomed-romance crime thrillers of the time are held — a keening search for meaning, transmitted through the blues, aching with negative space and basking so evocatively in its minor-key mournfulness that it’s almost startling when the music briefly diverts into a major key. (Further variations on that feeling, especially the subtly bitterer closer “Chez le photographe du motel”, wind up conveying a sort of exhausted fatalism on top of it.) “L’Assassinat De Carala” plays like both the stalking of a murder victim and the victim’s descent into the grave, with a minimalist, crawl-paced tension that embodies anticipatory dread and after-the-fact sorrow all at once; it’s the kind of evocation of fear and guilt that Davis’ more open-ended modal playing gave fluid nuance to. And even the uptempo numbers like “Sur l’autoroute” and “Diner au motel” nail a certain on-the-run desperation with fusillades of trumpet/sax solos and interplay that scan like they’re scrambling for purchase — it sounds like a sardonic yet sympathetic response to the ennui and frustration of schemers going nowhere fast.

![Novecento (1900) [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/4773279641370624_v1_600.jpg)

![The Hateful Eight [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/4885062352896000_600.jpg)

![The Good, the Bad and the Ugly [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5694300104949760_600.jpg)

![The Mission [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5707344927260672_v1_600.jpg)

![Bullitt [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/6594174740594688_600.jpg)

![The Pink Panther [Music From the Film Score] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5749366925033472_v1_600.jpg)