Recommended by

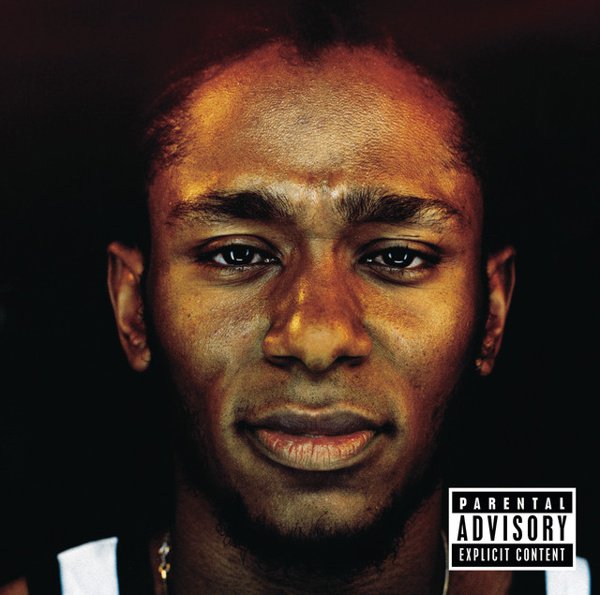

Black on Both Sides

The dust had barely settled from the impact of Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star before the group’s elder half dropped his solo debut full-length just over a year later. And he proved to be capable of some of the most dynamic, genre-warping, expansively thoughtful hip-hop the end of the ’90s had to offer with Black on Both Sides — a title that, if anything, understates how many facets he actually had by this still-early point in his career. From a perspective that fused ’80s old-school epiphanies, early ’90s jazz-rap expansions, and a polygot style that anticipated hip-hop’s 21st century status as an ever-broadening overgenre, Mos approached underground hip-hop as if it was the basis of the culture rather than an alternative break from it. And even as this meant he’d treat what appeared to be genre detours (screaming over a Bad Brains outburst on “Rock N Roll”; unshowily singing over cosmic soul-jazz on “Umi Says”) like foundational elements, his mic presence is a lot more direct and blunt in its delivery and messaging — he feels more accessible than most of his peers because his wordplay and his depth, while crucial to his art, are secondary to the fact that he sounds attention-demanding even when he’s being plainspoken. There’s nothing convoluted or overly abstract about the lovestruck way he wrestles his heart between romance and libido (“Ms. Fat Booty”), the perception behind his fears for an uncertain environmental future that spirals out from third world suffering to first world oppression (“New World Water”), or the clear-eyed frustration as laments how no amount of money or style can insulate Black people from the double-standard judgments and success-breeds-suspicion anxieties of racism (“Mr. N—-a”). And since that directness is paired with a remarkable sense of beat-jousting timing — he’ll sink into a rhythm so fluidly that it makes each emphatic shift or detour in his flow feel like a perfectly-placed joy-buzzer shock — he can inhabit a beat by DJ Premier (“Mathematics”) or Ali Shaheed Muhammad (“Got”) or his own self (“Fear Not of Man”) like he’s already known it for years.