Electr-O-Pura

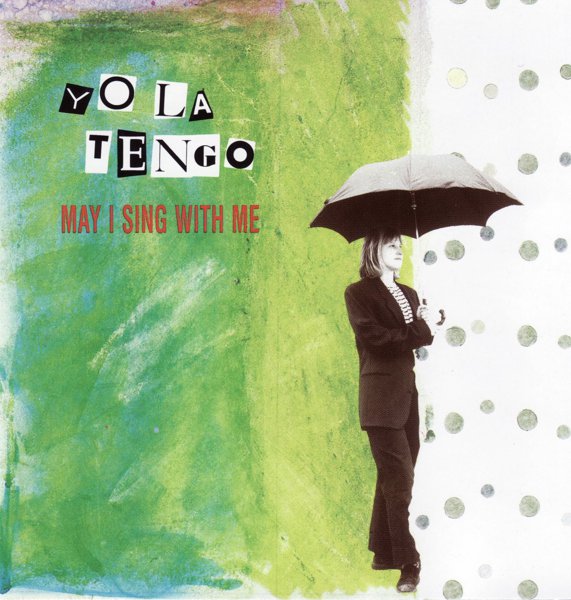

The second album Yo La Tengo released on Matador sometimes feels like the well-behaved middle child of a definitive three-LP run: Painful was a revelation, and revelations are hard acts to follow, while I Can Hear the Heart Beating as One eclipsed it as the bold we can do anything step that made them permanent critical favorites. Pinpointing what’s great about Electr-O-Pura feels a little elusive by comparison, while also being a little obvious, too: it’s not quite more-of-the-same or a departure, just a strong revisit of some of the more energetic and intense qualities of May I Sing With Me while still retaining the power of the heavy-calm paradox that Painful revealed. Then again, sometimes all you have to point out is that this is the one with “Tom Courtenay” on it. Every Yo La Tengo album of their Matador run has one of those “this is why they’re great” songs, but few of them really land in the wheelhouse this distinctively: it’s anthemic without being bombastic, catchy and energetic without sacrificing its melancholy, and namedropping another era’s and country’s pop culture icons (“Julie Christie, the rumors are true…”) not out of some smug trendsetter cool-spotting but because they found something genuinely fascinating to examine in the way those icons could spur longing in the people who watched them well after their prime. That’s the kind of thing that can happen when the songwriting core of a band includes a couple who complements each other by turning each other on to odd pop-cult corners they hadn’t yet fully discovered on their own, especially when that sense of exploration rubs off on the audience. (See also “The Hour Grows Late,” where Ira Kaplan namedrops the singer of a thrift-store find so obscure it still doesn’t show up on Discogs but makes it sound more like a secret world being unlocked than an obscurantist boast.) Electr-O-Pura feels like them engaging with rock history in a way that feels necessarily revisionist, working through the evolution of a sound that was starting to sound like a milieu the Velvet Underground couldn’t anticipate on their own. It helps that they successfully threw themselves into the mechanics of kosmische and post-rock as if these obscure, esoteric if-you-know-you-know scenes were just right there for anyone to get. Though sometimes it got them first: “False Alarm” is such a trip because its herky-jerky organ-jabbing Kraut-funk sounds like a big unwieldy idea the band has to wrangle into shape, to the point that it feels like it’s what the song is actually about (“Well if I open my eyes, if I just pay attention to McNew/Well, I just held back back back to listen to your cues”). So they met expectations even as they were starting to figure out how to shake them or even subvert them — they even went so far as to tweak the purists who still clung to punk’s slow plus long equals bad bias by tacking deliberately inaccurate, shorter track times to the songs on the back cover. It just worked because it’s easy to trick people into listening to songs that are longer than six minutes when — like the separation-anxiety freakout “Flying Lesson (Hot Chicken #1)” or the epic finale “Blue Line Swinger” — the way they elaborate from yearning quietude to hectic ferocity makes them actually feel shorter than they really are.