Recommended by

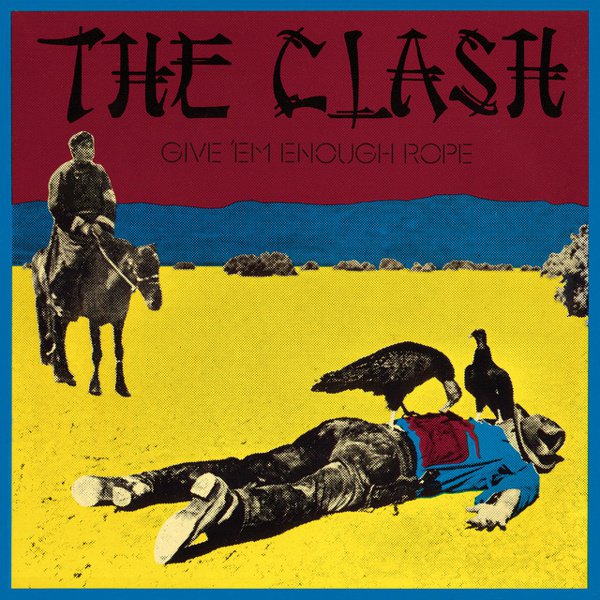

Give ‘Em Enough Rope

At its earliest moments, punk was intent on establishing the importance of being DIY and operating outside of the system and taking absolutely nothing seriously about the mainstream arena rock world. The Clash recording their second album on a major and getting Sandy Pearlman behind the boards appeared to fly in the face of all that, even if it seems like a lateral move for a producer who’d worked with the Dictators and Blue Öyster Cult. (“This ain’t the summer of love” and “no Elvis, Beatles or the Rolling Stones in 1977” weren’t exactly diametrically opposed perspectives — or sounds.) The purists might’ve had a point about the mixing, which does knock the album’s character down a notch; the addition of Topper Headon definitely made the band sound better, but mixing his drums louder than the vocals was a mistake. Aside from that, though, Give ‘Em Enough Rope is one of those transitional albums that offers a more refined but still uncompromised update of a band’s approach and promises even better things to come (even if you don’t factor in that the “better things” is the almost universally-loved London Calling). The key is in the sequencing, as they get the anger and fear and frustration out early on and eventually reveal their more vulnerable and empathetic side by the end of the LP. In some ways, that makes the album feel front-loaded, and this material’s some of their most lacerating — and not just because their guitars have rarely sounded meaner. There’s a conflicted ambivalence in the sardonic self-critique of “Safe European Home,” which both indulges in and interrogates their feelings of displacement during their time in Jamaica as white cultural tourists in over their heads. It feels even more stark in the way “English Civil War” and “Tommy Gun” riff off each other as political inquiries — when the right wants you dead, how much blood is acceptable for the left to spill? — and finds this band locked in a struggle between idealism and doubt. But after a mushy middle where they still sound like they’re figuring a few things out (with the UK scenester proto-Warriors scenario of “Last Gang in Town” a highlight), the last three cuts reveal the more sophisticated if no-less incisive Clash as they’d come to be appreciated by the end of the decade. “Stay Free,” Mick Jones’ tough-but-tender ode to an old mate turned criminal, is the best possible proof that early punk could be nakedly sentimental without compromising its edge. Strummer has rarely sounded as wounded in his anger — as singer, co-songwriter, or guitarist — than he does in the oft-overlooked “Cheapskates,” where he lays out in no uncertain terms that he and his mates aren’t the made-for-life rock stars that their detractors think. And as for their musical peers (and rivals) worried about getting caught up in the machinery? The origin story of “All the Young Punks (New Boots and Contracts)” depicts the Clash themselves by making their mythology out of ordinariness: they’re in a band not to find fame and fortune but because they’re not cut out for factory work, and what else could be there out there for a bunch of dead-enders like them, anyways?