History of Juju Music Vol. 1

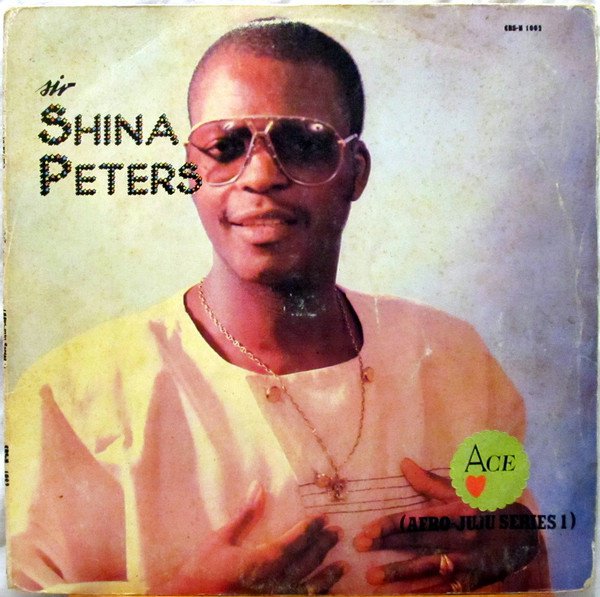

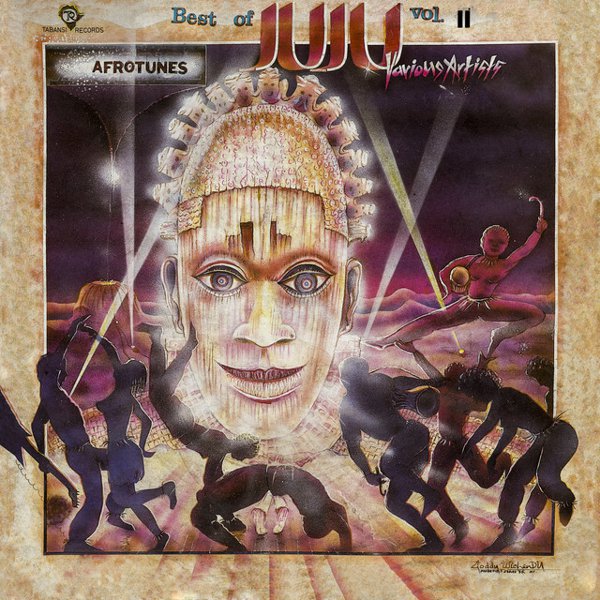

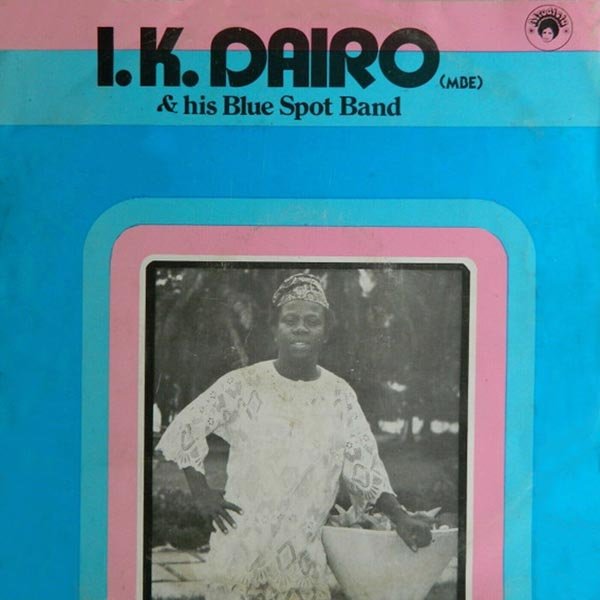

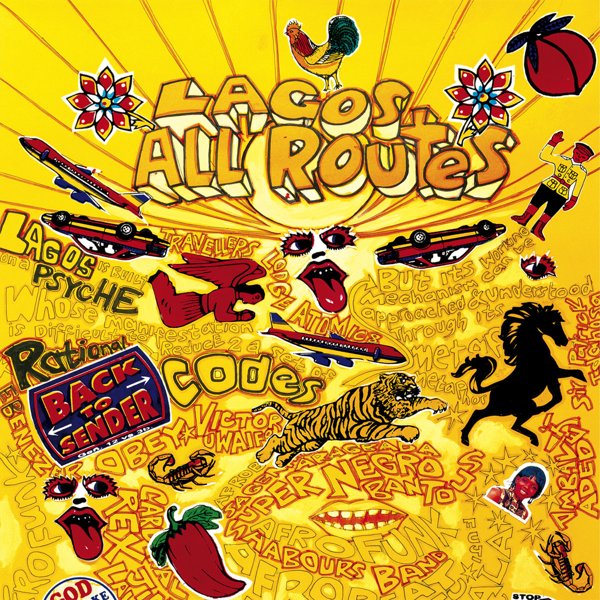

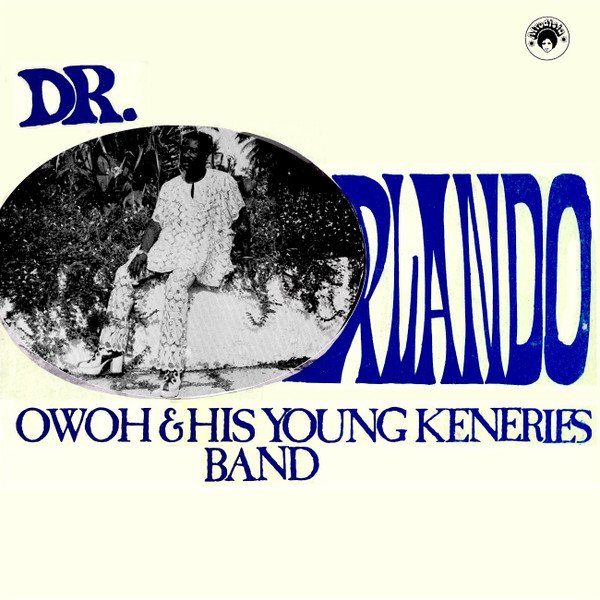

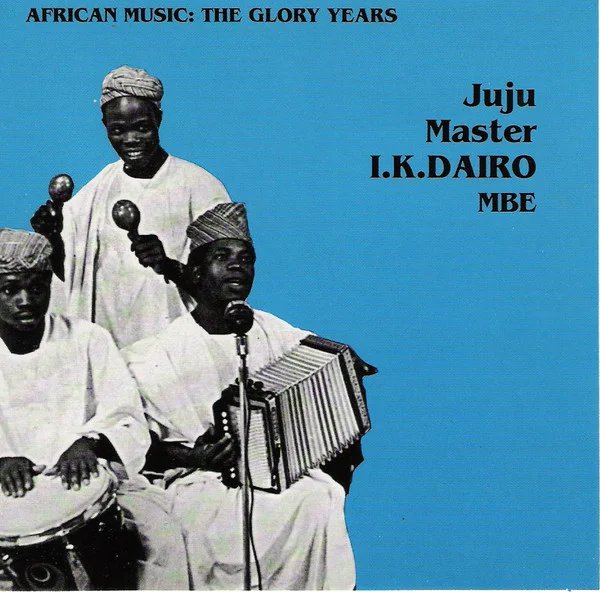

A comprehensive look at the development of jùjú, starting from its early days until its latest iterations in the 1990s with some interesting analysis on its origins and influences in Volume 3. The first volume begins with two of jùjú pioneer Tunde King’s earliest recorded tracks, where he is accompanied by tambourine, guitar-banjo, and sekere. Irewolede Denge’s track “Orin Asape Eko” is a simple, melodic tune where voice and guitar take center stage, as opposed to Ayinde Bakare’s next two tracks, where percussion is the driving force. By the time the compilation gets to the music of I.K Dairo in the 1950s, you can hear just how much it changed in only a few decades. The music is much richer, with the addition of the mouth organ, accordion, talking drum, and echoes of more traditional Yoruba music. Volume 2 picks up in the 1960s with the music of Dele Ojo, an apprentice of highlife musician Victor Olaiya who remained popular throughout his life and even toured the United States (his political track “Freedom for all Black People,” recorded in the US, is also featured on the compilation — hold on for the incredible breakdown). By then electric guitars were ubiquitous, as you can hear in the music by Tunde Nightingale, one of the first jùjú musicians to become a star after World War 2. His style, full of the praise and incantations that won him the favor of Lagos’ rich socialites, was known as “s’o wambe” (is it there?), a risque reference to the beads worn by women under their clothes. Finally, the 1990s are represented here by Chief Commander Ebenezer Obey, who, in his typical style, sings God’s praises in both tracks. Volume 3 is a great overview of jùjú music, and includes both music and spoken sections explaining jùjú’s genesis and influences.