Afrobeat might be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of Nigerian music, but for close to a century it’s another style that has been the most widely and consistently popular in the West African country. Jùjú emerged in the 1920s in the drinking establishments in Olowogbowo, a Lagos neighborhood mostly inhabited by Saro people, and some ethnomusicologists even trace it back to a specific group of friends who would gather in Till Nelson ‘Akamo’ David’s motor mechanic “workshop15.” Since then jùjú has evolved both conceptually and in practice, closely mirroring the immense social, political, and economic transformations which have swept Nigeria during the 20th century.

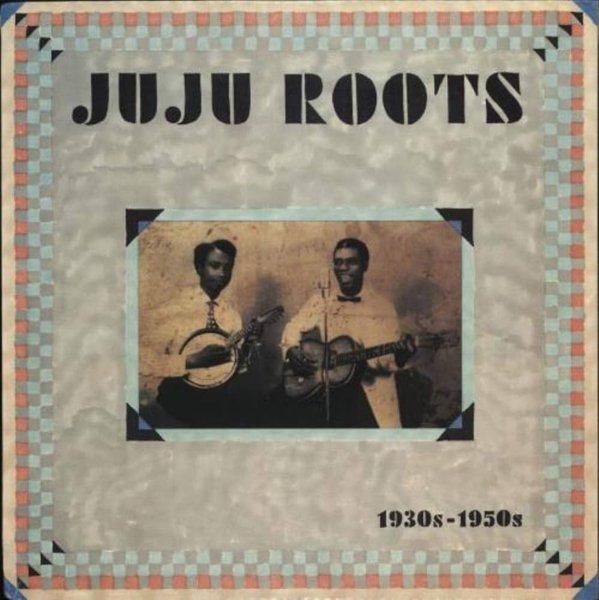

In the early days, before it was known as jùjú, the style emerged from the combination of different Nigerian and “imported” traditions that all came together in Lagos. On the one hand was Yoruba drumming, Christian church melodies, and traditional asiko dance music, while on the other were the sea shanties of the Liberian Kru sailors, the samba of Lagos’ Brazilian community, and the introduction of the tambourine drum by the Salvation Army Missionaries. All these different elements came together in this new, syncretic style, in which one person would sing while others would accompany with a box guitar or banjo, as well as making rhythms with cigarette boxes, bottles, and empty palm-wine kegs. The lyrics were usually about important events in a person’s life or that of the community, and carried reflections on morality and virtue.

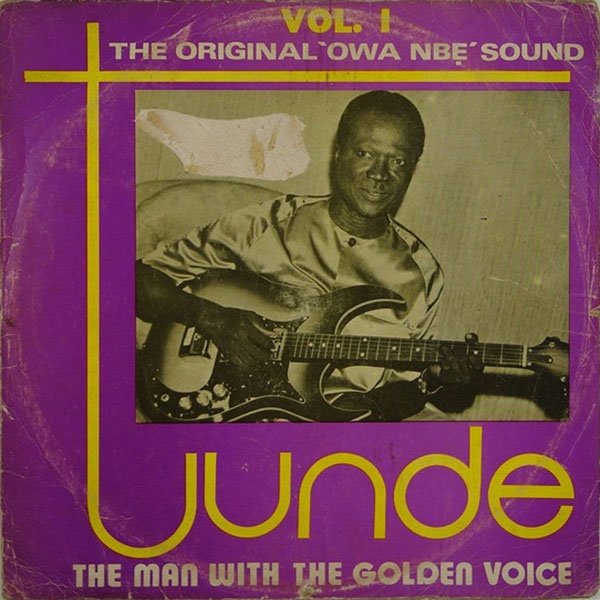

This is the context in which Tunde King, one of the boys who would gather at workshop15, emerged as an early Jùjú pioneer, influencing a whole generation of musicians — Ojoge Daniel, and Ayinde Bakare, Ojo Babajide, and Tunde Nightingale to name a few — and making the first jùjú recording in 1936. He is also credited with coining the term jùjú, which means “throwing in Yoruba,” an allusion to the way a musician in his band would throw a Brazilian, tambourine-like drum up in the air before catching it again.

During these first few decades jùjú became an increasingly popular choice at ceremonies and in taverns across Lagos, but its instrumentation and musical style remained largely the same. This changed with the introduction of the Yoruba talking drum by Akambi “Ege” Wright. Not only did this small hourglass-shaped drum contribute its distinctive sound, which can mimic the tone patterns of human speech, but it also brought with it other aspects of Yoruba musical tradition, such as traditional proverbs and praise singing. At the same time another musician, the Kruman Sunday Harbour Giant, included the penny whistle flute, mandolin, and organ in his ensemble. According to Prof. Afolabi Alaja-Browne these additions were due to the competition between local groups who were all trying to come up with the most unusual and innovative sound to win the favor of local taverns and their patrons. The advent of electric amplification after World War II further enabled the introduction of new instruments, such as the electric guitar.

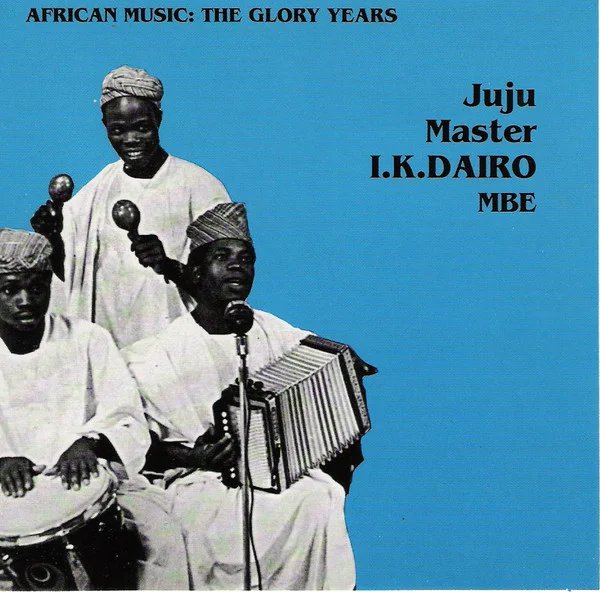

The true break between “old” and “new” jùjú music can be attributed to Isaiah Kehinde Dairo, who expanded the traditional ensemble to include the accordion and mouth organ. Diaro also turned his attention to regional singing styles, rhythms, and melodies, and by singing in dialect and introducing more traditional elements, he broadened jùjú’s appeal outside of Lagos and deepened its connection with Yoruba culture countrywide in the pivotal time leading up to independence. Dairo became the first jùjú musician to become a country-wide star, and released many hit songs with his band the Morning Star Orchestra (later the Blue Spots).

Although he remained popular until the 1990s, Dairo would soon be overshadowed by two artists who would go on to become Jùjú’s biggest stars: Ebenezer Obey and King Sunny Ade. Their careers, which started in the mid-’60s but really took off in the ‘70s, would be defined by an intense artistic rivalry that sparked a period of creativity and innovation for Jùjú music.

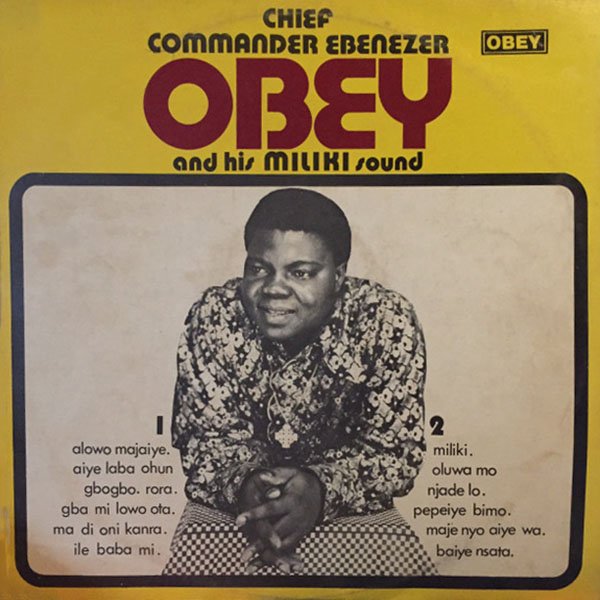

Chief Commander Ebenezer Obey began his career playing with Fatai Rolling-Dollar’s band, but soon left to form highlife-jùjú fusion band The International Brothers, which then became the Inter-Reformers when they began playing straight Jùjú. Obey increased the size of the Jùjú ensemble, adding more guitars and talking drums, and performed extended dance tracks that brought together both Christian messages and Yoruba tales. He and his band specialized in praise-singing, the practice of extolling the virtues and qualities of an individual, usually a rich socialite or business tycoon.

This transformative period for jùjú coincided with Nigeria’s oil boom, and as money poured into the country and people gained influence and affluence, praise-singing took on a more prominent role within popular music and enabled musicians like Obey to become millionaires.

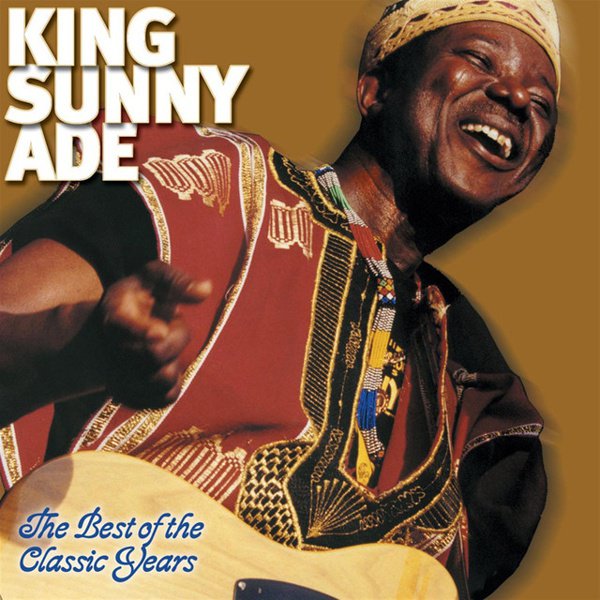

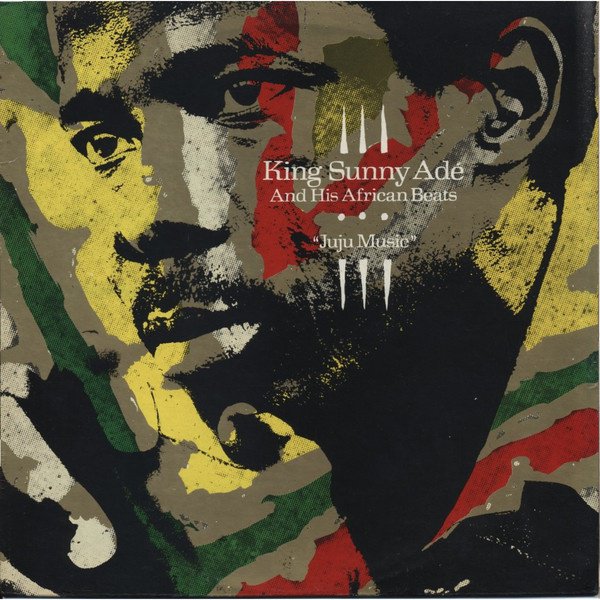

King Sunny Ade, too, appealed to the rich and powerful, but had more of a populist appeal with his fast-paced dance songs which often contained thinly veiled sexual innuendos. Born into a poor family of royal lineage in Ondo Kingdom, he moved to Lagos and played in Moses Olaiya’s highlife band before moving on to start his own band The Green Spots, and over the years further expanded his band (which went through more than a few name changes) to include several guitars, incorporating a steel guitar for the first time, as well as different percussion instruments and synths.

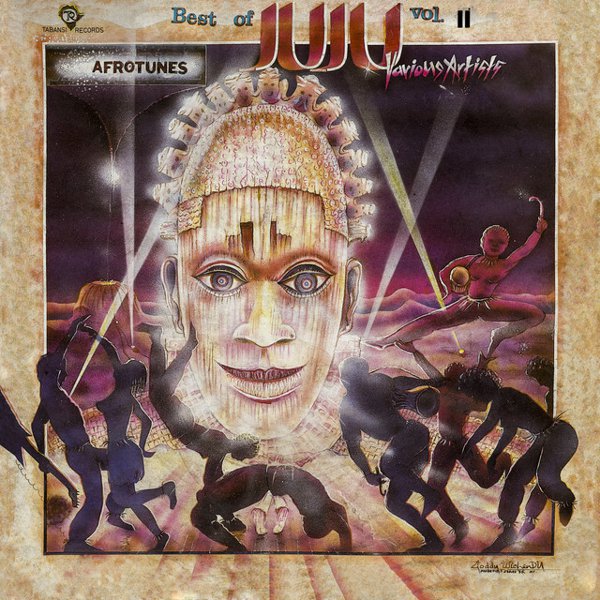

Both Obey and Ade had an immense impact on the evolution and popularization of jùjú in Nigeria, but it was Ade who introduced it to the rest of the world with his 1982 album Juju Music. Although musicians like Miriam Makeba, Fela Kuti, Manu Dibango and Hugh Masekela had released music and toured in the US before, none of them had had a major commercial success (except maybe for Dibango’s massive 1972 hit “Soul Makossa’’). Island Records recognized Ade’s star potential and thought he could achieve the same level of global success as their late artist Bob Marley. While he never even got close, Juju Music was both a critical and commercial success.

Back in Nigeria Obey also continued to release hit after hit, and his songs soundtracked Yoruba weddings and ceremonies. However, the tide was about to turn: following the optimism of the 1970s, the Nigerian economy began to deteriorate in the 1980s. The 1990s dawned with a coup d’état, marking the beginning of military rule and the suppression of cultural expression. Ade and Obe continued recording and performing, but much less frequently, and the sun began to set on jùjú’s heyday as synthpop, disco, and fuji began to take over.

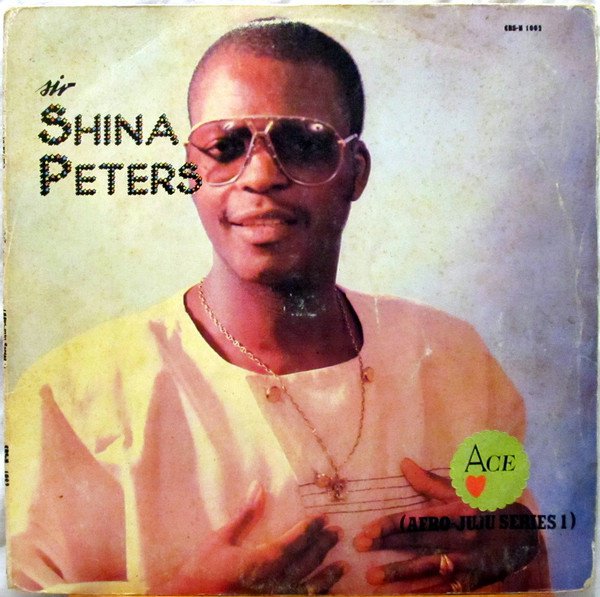

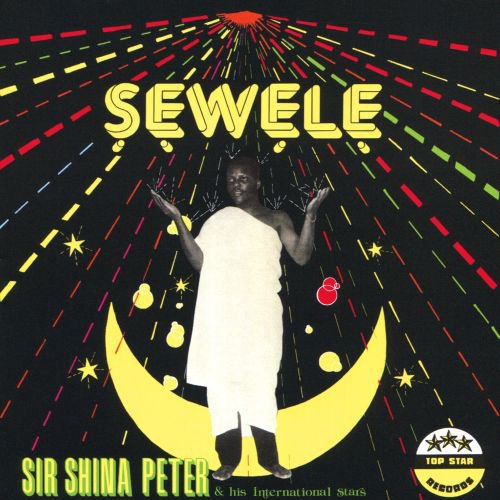

When it seemed like the jùjú era was all but over, a new chapter in this versatile musical genre arrived in the form of Sir Shina Peters. Although he had spent time playing in Obey’s band, Shina borrowed his provocative style and racy lyrics from King Sunny Ade, but did away with the Hawaiian guitar Ade had introduced in favor of faster, heavier fuji-style percussion, futuristic synths, and Afrobeat rhythms. He called this style “afrojuju”, and although he’d already released a few albums (like the 1986 Sewele, which marked a turning point in the search for his own personal style) it was Ace which would propel his career to new heights and kick off a period of “Shinomania.”

Since then no other musician has come forward to claim Peters’ crown, and it’s been decades since a jùjú record has come close to topping the charts. But the genre is far from dead: local jùjú bands still draw the crowds in Lagos bars, and Ade and Obey’s hits are ubiquitous at weddings and other celebrations.