Recommended by

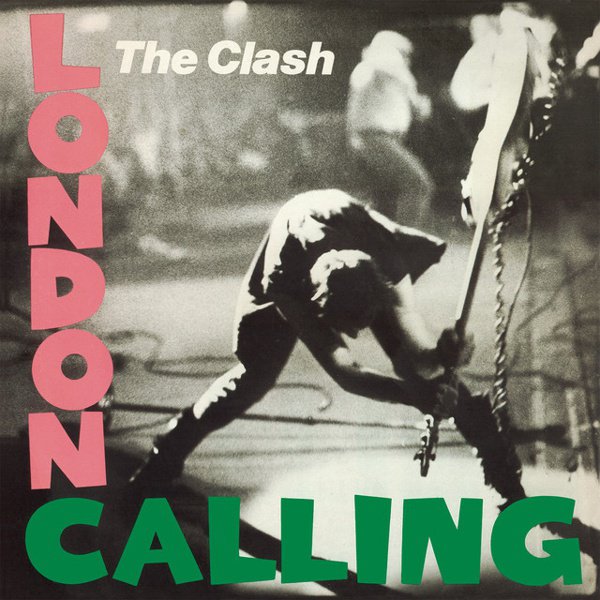

London Calling

It’s a funny quirk of fate and/or record industry machinations that the Clash’s third album was one of the last great records of the ’70s in the UK and one of the first great albums of the ’80s in the States. But those designations fit, every bit as much as its omega-to-Elvis’s-alpha cover art does: it marks the end of a troubled but creatively rich era for rock’n’roll, whether you’re talking about one of music’s most unpredictable and tumultuous decades or the longer-term era of rock itself as the primary standardbearer of pop. Within a few years, the big-hit revolutions would come more frequently from synthpop and R&B and eventually hip-hop, mainstream rock’s return-to-the-roots impulse would start to choke on its own self-importance, and the kinds of bands capable of albums like London Calling, while numerous and influential, would be increasingly diverted towards creatively fulfilling but less-accessible indie channels you had to seek out just to know about. But London Calling doesn’t fall into any of those traps. Its history-savvy eclecticism feels neither confrontationally esoteric nor overly reverent, and it if was meant to be an exegesis on What Rock Meant, it was better at showing this than telling it (and, in the long run, proving it more than both). The telling, of course, is still some of the most evocative in pop music history: the Strummer/Jones partnership was still more complementary than combative at this point, and the way their ideas of romanticism, rebellion, amusement, and profundity all played off each other meant they could find the emotional knife-twist in any subject they tackled. It could be the about the people who see the hollowness at the root of the consumerist impulse (“Lost in the Supermarket”) or the blow-addled strivers who engineered it (“Koka Kola”), the fascists who ran rampant during Franco (“Spanish Bombs”) or the go-along-to-get-along enablers crawling out of the woodwork under Thatcher (“Clampdown”), the misfits who had everything and lost it over the course of a slowly declining career (“The Right Profile”) or just one star-crossed night (“The Card Cheat”) — all put together with some of the sharpest, wittiest lyrics to ever make tape. (Listen to “Death or Glory” once and you’ll be forever haunted by the couplet “But I believe in this and it’s been tested by research/He who fucks nuns will later join the church.”) Plus their covers proved how important it was to hold contemporary reggae like Danny Ray’s “Revolution Rock” in the same esteem as Vince Taylor’s ’59 rockabilly gem “Brand New Cadillac” — and how at home they’d come to feel in both those genres. This was one of those double LPs that justified its length because the Clash had fully coalesced into a band that saw the potential in nearly every style of music and the best routes through it, from the opening title cut’s distillation of punk fury into martial-paced doomsaying to the last-moment inclusion of “Train in Vain,” the ironically upbeat breakup recrimination that proved they could do the pop-disco-punk thing better than anyone East of Blondie. Sure, London Calling wasn’t the last truly great mass-market rock album by a longshot, but it does feel like one last big culmination of everything that made rock great before it splintered into a hundred adversarial subcultures.