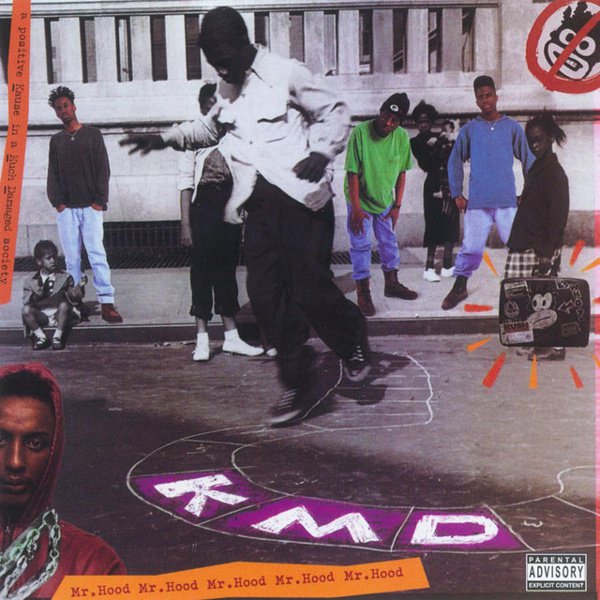

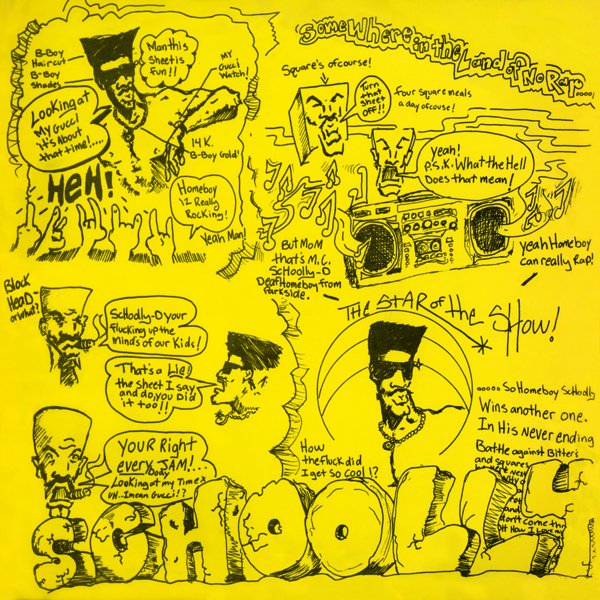

Mr. Hood

A decade before Operation: Doomsday made him the most compelling supervillain in hip-hop, the man who would be DOOM was rapping under the name Zev Love X alongside his brother Subroc in a crew known as KMD. (The fact that this name stood for Kausing Much Damage but was retrofitted into A Positive Kause in a Much Damaged Society says a bit about the multitudes they contained.) Capitalizing on a memorable guest turn on 3rd Bass’s “The Gas Face” with a full-length debut on Elektra, KMD’s Mr. Hood is an album that equally feels like a should’ve-been-bigger lost classic and one of those bizarre miracles that it’s hard to imagine most labels even taking a risk on in the first place. Zev and Subroc’s production chops and soundscaping have all the irreverent, youthful anything-goes anarchy of Prince Paul’s contemporaneous work with De La Soul — already something of a novel outlier in early ’90s hip-hop. But there’s also enough Five-Percenter perspective to put them in the same philosophical ballpark (and, for “Nitty Gritty”, the same studio) as Brand Nubian, leading to this striking mixture of deep-thought Afrocentrism and manic, comedic silliness. So you get samples of Bert from Sesame Street cackling not only over the tangled language of rap-about-whatever “Humrush,” but on the anti-caricature paean to Black self-knowledge “Who Me? (With an Answer from Dr. Bert),” you get elaborate skits that feel like overheard conversations (“Mr. Hood Meets Onyx”) and conversational raps that merge confrontational frustration with sardonic humor (“Bananapeel Blues”), you get metaphors within metaphors within more metaphors (“Hard With No Hoe” is farming analogy as relationship-woes gag as racial-stratification examination). It’s also just straight-up fascinating to hear the Dumile Brothers in a formative mode: listening for future signs of DOOM’s characteristic phraseology reveals just how complex Zev’s abstractions could be so early in his career (from “Trial ‘N Error”: “Range is point blank but my page ain’t/You see I speak bold print like black spraypaint”), and god knows Subroc would’ve followed him into that same rarefied turf if he hadn’t died tragically young less than two years after Mr. Hood dropped. But before all that, they got the opportunity to shine as both lighthearted, college-radio-friendly teenage absurdists and knowledgably strident activists — too complex to fully blow up the mainstream, but too unique to ever be forgotten by an audience smaller than they deserved.