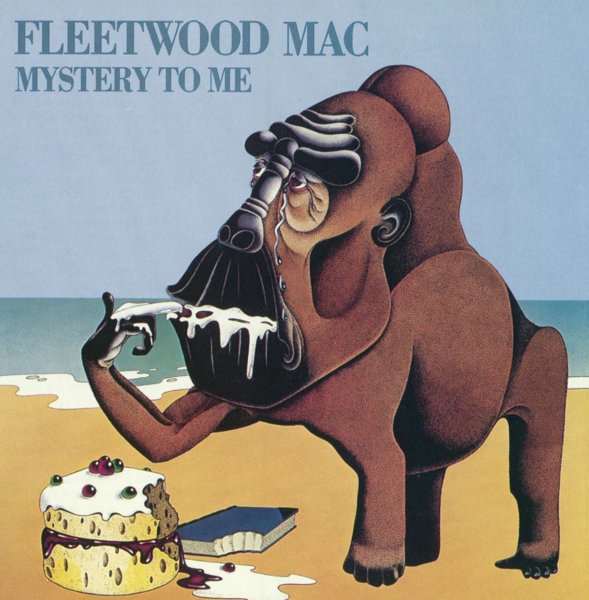

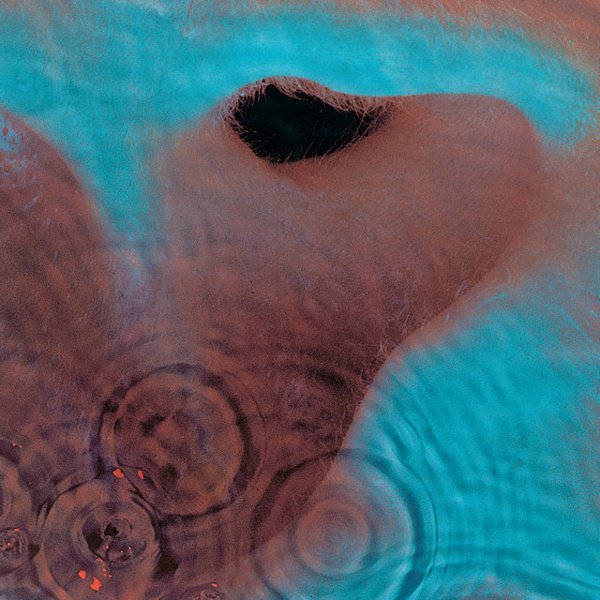

Mystery To Me

The Buckingham/Nicks era of Fleetwood Mac was such a commercial and creative juggernaut that their previous incarnations tend to get shorter shrift in surface-level rock history retellings. But there’s plenty of gold in the material they recorded during what now seems like a transitional phase — when they were the most intent on transcending their blues-rock origins, yet still searching for a new Trans-Atlantic Cali-simpatico sound. And the brief but crucial stretch of albums centered around the prominence of Christine McVie and Bob Welch as the group’s primary songwriters peaked with Mystery to Me, an album that dug deep into the symbiosis of mellow reflection and the curiosity of the unknown — smooth enough for soft rock, but with a lingering post-psychedelic fascination with the intangible curiosities in life. Romantic infatuation is depicted as both emotionally necessary and intellectually bewildering in “Emerald Eyes,” the FM cult hit “Hypnotized” treats Castaneda mysticism and UFOlogy with a bemusement that shrugs off skepticism, and “Forever” (the one John McVie co-write) sinks so deep into its escapist reverie that even its acknowledging the transitory nature of it all (“just let me stay that way”) feels closer to enlightenment than defeat. Still, it’s not all easy-breezy; the uptempo yet fatigued blues-rock of “The City” laments the inhospitability of New York in ways that the Sex Pistols and Fear couldn’t quite nail down in all their fury, and “Somebody” is every bit as bitter a lovers’ recrimination as anything to come from the high drama of the Rumours/Tusk years. There are moments on this album where you can hear the world-beating hit machine to come: “Just Crazy Love” is the kind of Christine McVie showpiece that would make “Say You Love Me” feel like a fait accompli, and the string-stabbed proto-sophisti-pop of “Keep on Going” flaunted their facility with shifting forms of groove. But there’s enough of a compelling self-contained world in here that the whole “transitional phase” aspect, and all the drama beneath its surface, seem like an afterthought no matter what lie after that transition.