Recommended by

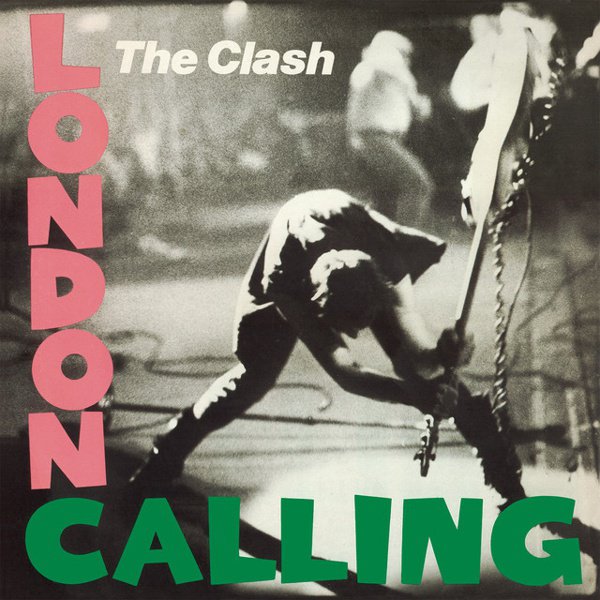

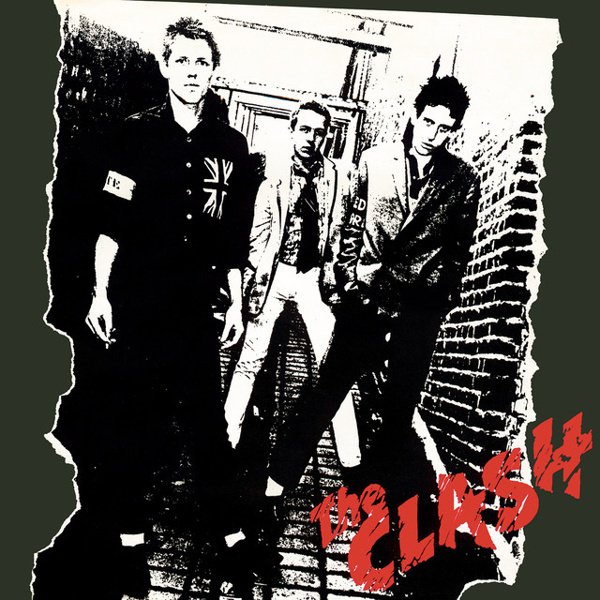

The Clash

Given all the hagiographic mythology that’s been ladled on punk rock’s class of ’77, and especially considering what the band did afterwards, there might be a case to be made that the revolutionary impact of the Clash’s first album might be a little overstated. But it’d be a pretty flimsy case, predicated either on hardliner purism (“They’re on CBS! Not punk!“) or, more likely, the fact that 95% of the bands who tried to sound like this for the next 40-plus years couldn’t pull it off nearly as well. Maybe it’s because The Clash considered punk’s spirit of musical amateurism to be the means rather than the end; as a band they knew that the only way to make that chaotic-yet-simple musical aggression sound more dangerous was to play it with both unorthodox adventure and intense precision. The former quality would emerge a little later, though their herky-jerky mutation of Junior Murvin’s then-recent hit “Police & Thieves” was a promising sign of a broader punk/reggae hybridization to come. And the latter was obvious to anyone with a love for rock’n’roll’s bare fundamentals, whether you’re talking the exuberantly surly force of the Paul Simonon/Terry Chimes rhythm section, or the way Joe Strummer and Mick Jones’ Ramones-via-Kinks guitar interplay held lots of subtle counterpoints and call-and-response flourishes. And maybe another reason The Clash endures is that they’re not just angry on behalf of themselves. This is an album that kicks off — at least in the original UK pressing — with “Janie Jones,” a song that zeroes in on the kind of lonely, horny, dope-smoking loser that most other punks would set up as a punchline; that Joe Strummer gives an acidic-yet-warm presence to a character who’s also defined by how much he hates his shitty job (see also: “Career Opportunities”) makes it feel like he’s actually been that person. But Joe and songwriting partner Mick Jones are interested in being a lot of people: the abused, directionless youth who’s left with no recreational options besides violence and crime (“What’s My Name”; “Hate and War”), the class-conscious, solidarity-minded lefties who wonder why there aren’t more people like them agitating for change (“White Riot”; “I’m So Bored With the U.S.A.”), even an embodiment of their surroundings’ collective ennui (“London’s Burning”). Sure, the repackaged ’79 US version’s got better songs than the UK pressing — it’s pretty amazing that they went from the simple provocations of “Protex Blue” and “Cheat” to the glorious conflagration of “Complete Control” so quickly — but their power, and their purpose, was clear from the beginning.