On September 2, 1945, the Japanese empire agreed to end hostilities with the Allied forces, officially ending World War II. The terms of the surrender allowed the Allies to occupy Japan, setting up a military presence in the region. Through to the end of the occupation in 1952, it is estimated that over a million American servicemen were stationed in Japan at some point; with them, they brought a flood of American culture.

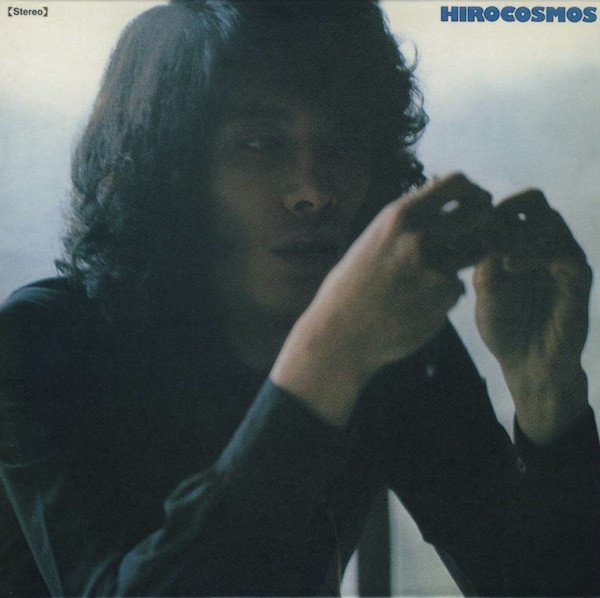

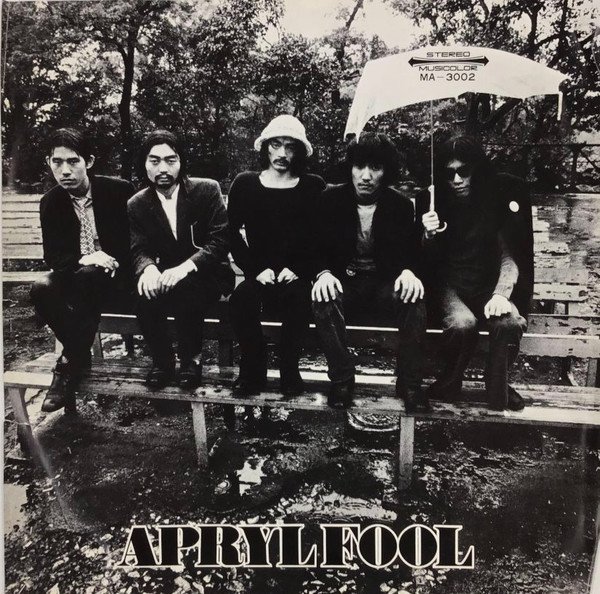

“I was born in 1947,” Haruomi Hosono recalls in an interview with the Red Bull Music Academy, “two years after the end of World War II.” He remembers hearing possibly more American music than music from Japan, even occasionally lamenting that he wasn’t from the United States. “The psychedelic movement was happening there when I was a teenager,” he says, recounting that he was listening to bands like Buffalo Springfield and Moby Grape while he was still in high school. Naturally, when he started making music of his own, he drew from the well of American folk and psych rock. His first band, Apryl Fool, was heavily inspired by groups like The Yardbirds, The Beatles, and The Rolling Stones. The group’s sole album wouldn’t be as commercially successful as his subsequent group, Happy End, but it set him on a path that would define his career as well as transform the landscape of Japanese popular music.

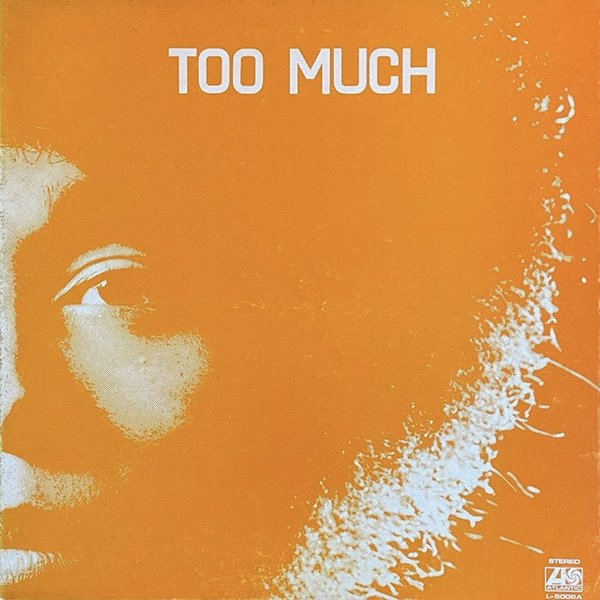

His story is typical of musicians from his Shōwa era generation. Many of Hosono’s contemporaries in the music industry – including every member of Apryl Fool – would continue fusing various flavors of Americana into their work. Chu Kosaka, for example focused squarely on the blues; Hiro Yanagida leaned more into psychedelic jazz-fusion on solo projects and in groups like Food Brain; Takashi Matsumoto followed Hosono and joined Happy End, but remained a prolific songwriter and producer well beyond his exit from the spotlight.

Something that drew Hosono, and doubtless many others, to folk from the US is the way it incorporated American roots music into its sound. “We realized that,” Hosono said, “and we thought about what our own roots were.” In Happy End, this manifested in the lyrical structure: they wrote in a free-verse style reminiscent of Taishō era poetry, even as the vocals more closely resembled the crooning of David Crosby. Other groups incorporated Japanese elements directly into the sound; Shoukichi Kina and his band Champloose mixed traditional Okinawan music with rock, bringing the three-string sanshin and min’yō folk singing into the fold.

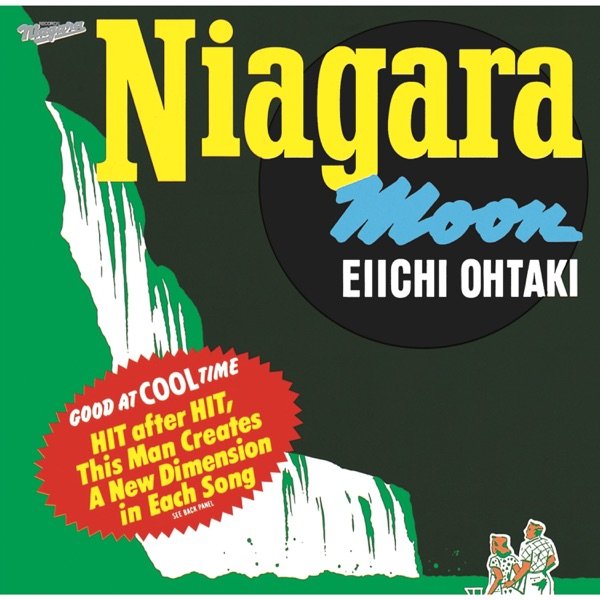

Japan’s folk rock boom was already beginning to lose steam by the mid 1970s – the majority of records on this very list released before ’75 – but the influence remains long lasting. Hosono pivoted to electronic music and kickstarted another revolution in Japan with Yellow Magic Orchestra, but would return to American roots and bluegrass again and again over the course of his long career. The late Eiichi Ohtaki, an alumnus of Happy End, would have his own successful career as a key figure in the city pop boom of the 1980s. His iconic singing style was developed by imitating American singers like Brian Wilson and trying to utilize their techniques even when singing Japanese lyrics. In thinking deeply about how much of their influences came from overseas, it reinforced the parts that are distinctly Japanese.

![古井戸の世界 [Fluid no Sekai] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/Fluid-No-Sekai_600.jpg)

![よだかの星 [Yodaka no Hoshi] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/Yodaka-No-Hoshi_600.jpg)

![のすたるじあ [Nostalgia] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/のすたるじあ--Nostalgia-_600.jpg)

![のぶえの海 [Nobue's Sea] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5740341580005376_v1_600.jpg)

![センチメンタル通り [Sentimental Dori] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/センチメンタル通り--Sentimental-Dori-_600.jpg)

![晩餐 [Social Gathering] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/Social-Gathering_v2_600.jpg)

![喜納昌吉&チャンプルーズ [Shoukichi Kina & Champloose] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/喜納昌吉-チャンプルーズ--Shoukichi-Kina---Champloose-_600.jpg)

![風街ろまん [Kazemachi Roman] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/風街ろまん--Kazemachi-Roman-_600.jpg)

![回帰線 [The Tropics] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/回帰線--The-Tropics-_v2_600.jpg)

![僕の声が聞こえるかい [Love Suki Daikirai] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/僕の声が聞こえるかい--Love-Suki-Daikirai-_600.jpg)

![浅川マキの世界 [Asakawa Maki No Sekai] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/浅川マキの世界--Asakawa-Maki-No-Sekai-_600.jpg)

![飛べない鳥、飛ばない鳥 [Love Songs and Lamentations] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/飛べない鳥-飛ばない鳥--Love-Songs-and-Lamentations-_600.jpg)

![ふたり [Futari] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/ふたり--Futari-_600.jpg)

![まちぼうけ [Machibouke] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/Machiboke_600.jpg)

![萬花鏡 [Mangekyou] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/Mangekyou_600.jpg)

![万華鏡 [Mangekyō] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/万華鏡--Mangekyo-_600.jpg)

![一触即発 [Isshoku Sokuhatsu] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5698013398302720_600.jpg)

![乙女の儚夢 [Maiden's Fleeting Dream] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/乙女の儚夢--Otome-no-Hakana-Yume-_600.jpg)

![ひらく夢などあるじゃなし [Hiraku Yume Nado Aru Janashi] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/ひらく夢などあるじゃなし--Hiraku-Yume-Nado-Aru-Janashi-_600.jpg)

![わすれがたみ [Wasuregatami] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/わすれがたみ--Wasuregatami-_600.jpg)

![壬生 [Mibu] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/壬生--Mibu-_600.jpg)