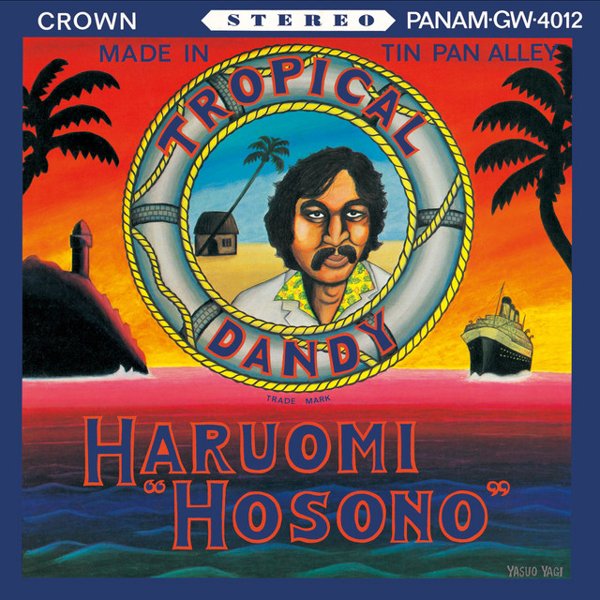

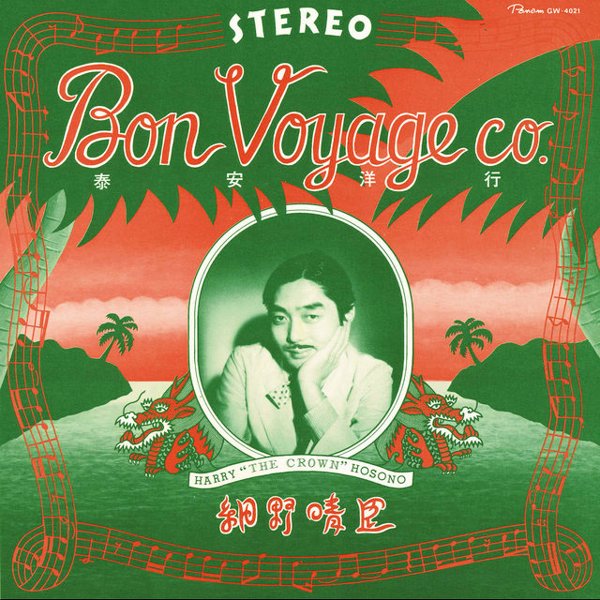

If it didn’t happen in real life, it could be a scene right out of an early 1970s Robert Altman film. Four hirsute long-haired Japanese rockers arrive in sunny, smoggy Los Angeles and their manager whisks them away to a recording studio similarly hazy with pot smoke. The band is called Happy End and they insist – via translator – on getting that “Burbank Sound.” Behind the boards is famed producer and one-time Beach Boys songwriter Van Dyke Parks and Little Feat guitarist Lowell George and neither one of them is quite sure what to make of the band before them. To hear Parks describe it, “they looked something like The Beatles, and I expected maybe they were just a little more cosmopolitan than me.” With Parks and George still baffled due to the language barrier, the band resorted to more common ground: a pearl as an offering as well as a suitcase stuffed full of $20 bills. Suitcase in hand, Van Dyke Parks produced what would become the group’s final studio album, Happy End. Having met one of his idols in Parks, Happy End bassist Haruomi Hosono embarked on an idiosyncratic solo career now entering into its sixth decade.

Happy End were not quite the Japanese version of the Beatles, but Hosono’s next band project came close to attaining a similar level of fanatical teenage fandom. In 1978, Hosono had a brainstorm, inviting two other Japanese session players, keyboardist Ryuichi Sakamoto and drummer Yukihiro Takahashi, over for dinner where he aired out his grand plan: “We will arrange Martin Denny’s ‘Firecracker’ as an electric chunky disco using synthesizers and sell four million copies of the single worldwide.” Which is pretty much exactly what happened when their new group, Yellow Magic Orchestra, became huge.

As Sakamoto explained, their mission was taking “that fake image of Asian culture, exotic, typical stereotype image—which Americans created in Hollywood!” and tweaking it to show how ridiculous the stereotype was. Taking their cue from these caricatures of Japanese culture, YMO inverted West’s fetishization of the East, holding up a warped funhouse mirror. But slot the group as “the Japanese Kraftwerk” at your own peril, as the group was just as trailblazing, with cutting-edge Japanese technology at their disposal. They were one of the first groups to deploy new gear such as the Yamaha DX7 and the TR-808 drum machine, the foundation for much of modern music, from hip-hop to electro to techno.

They even attained a curious level of success in the West. They once graced the Soul Train stage, befuddling Don Cornelius while getting the crowd to pop and jerk to them. Afrika Bambaataa added YMO to his crates for the infamous early hip-hop codex, Death Mix. Their music was played at the Paradise Garage and by The Electrifying Mojo on Detroit radio. Young producers like Kurtis Mantronik and Derrick May thrilled to every new YMO release. Michael Jackson recorded a cover of YMO’s “Behind the Mask” for Thriller, only to have YMO management scrap the idea.

But by 1983, intergroup tensions had scattered Hosono, Sakamoto, and Takahashi, and they began to follow their own solo paths. Hosono, for one, felt a great sense of relief. In the waning days of that stardom, Hosono would often retreat back to his hotel room to escape. “Whenever I was back in my room I’d cover the TV with a semi-transparent sheet and use it as a light source, and listen to minimal music like Brian Eno and the Obscure label,” he once told me. “Not long after that time, I DJ’d an event where I played a Gregorian chant simultaneously with a drum machine—that’s when I started to express those feelings I had towards that kind of music.”

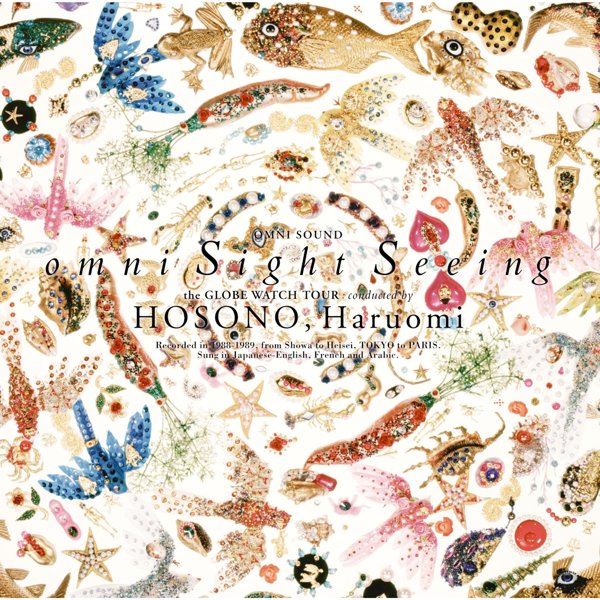

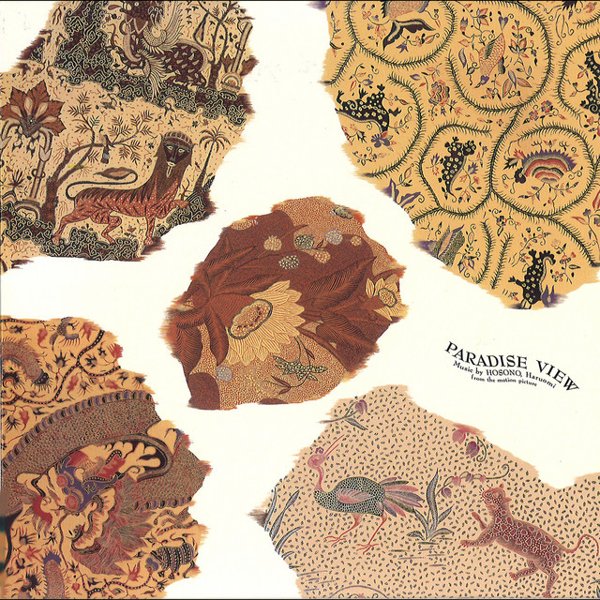

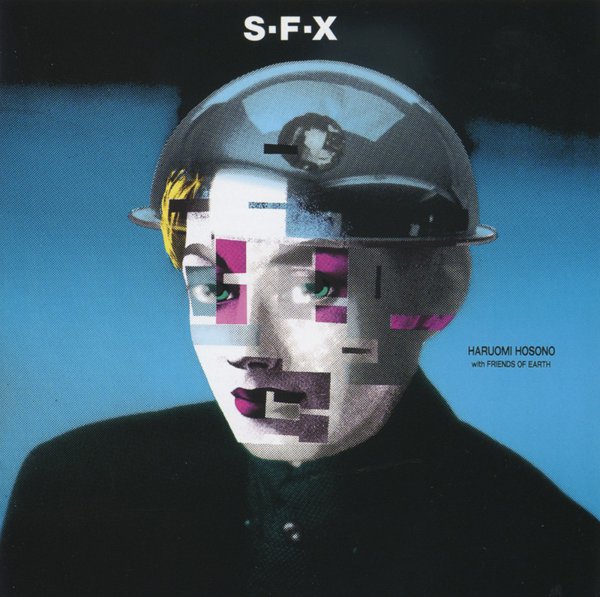

In the 1980s, Hosono went deeper into the machines. “What changed the way I create music was a micro-computer named Roland MC-4 and MIDI, which happened concurrently,” he said. “I tried out each new product that came out. The most unique of all, but the most difficult to operate, was the Yamaha DX7, but I eventually was able to figure it out.” Establishing his own label, he released a string of stunning solo albums that engaged with this nascent technology and the a-historical, brave new sounds possible with them.

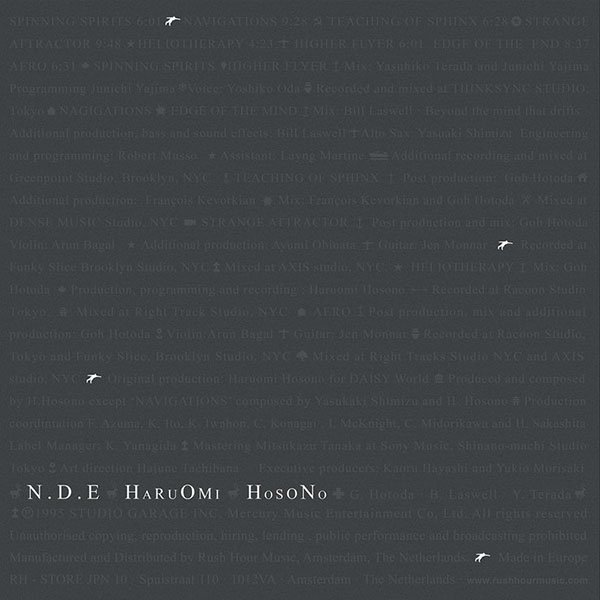

Hosono was one of the first artists to understand how electronics can be freeing: from virtuosity, from education, from nationality and culture, from ego. It offered its human counterparts a plasticity that allowed them to escape from established barriers. In turn, such electronics allowed Hosono to be seen in a new light. Hosono has at times resembled Neil Young, at other times Kraftwerk or Eno, while his electronic work in the late ’80s and ’90s made him kindred to The Orb, Bill Laswell, 808 State, Mixmaster Morris, and Atom Heart. His influence on modern music is wide-ranging, from underground techno producers to Harry Styles, fourth world ambient explorers to Mac DeMarco. And his most recent run of albums in the 21st century finds him coming full circle, to where he even totally re-imagined and reworked the songs on his 1973 debut some 46 years later to winsome effect.