Zoom in on any one aspect of Steve Albini’s activity in and around music from the early 1980s up through his sudden, shocking death in May 2024 and you might miss a larger truth: Each one of his numerous pursuits was essential to his overall project. Albini cared about underground music so much that it wasn’t enough to make it himself; he also had to help others realize, as he once put it to Tape Op, “the record of their dreams.” Likewise, it wasn’t enough to create and facilitate; he also had to critique the culture he treasured, sometimes in withering terms, but just as often in ways that passionately validated the act of devoting one’s life to creating challenging, uncompromising art.

All this means that anyone looking to properly assess his legacy and influence has their work cut out for them. The albums he recorded are as important as the ones he played on. And the many obscure titles he engineered tell us as much about how he engaged with the world — and maybe more — as the canonized classics. The same goes for the albums he championed that he played no actual role in. All of it was key to the ecosystem that he helped foster year by year, riff by riff, session by session, soundbite by soundbite. Taken together, the 20 records included here make up the beginnings of a composite portrait of Steve Albini’s activity and influence.

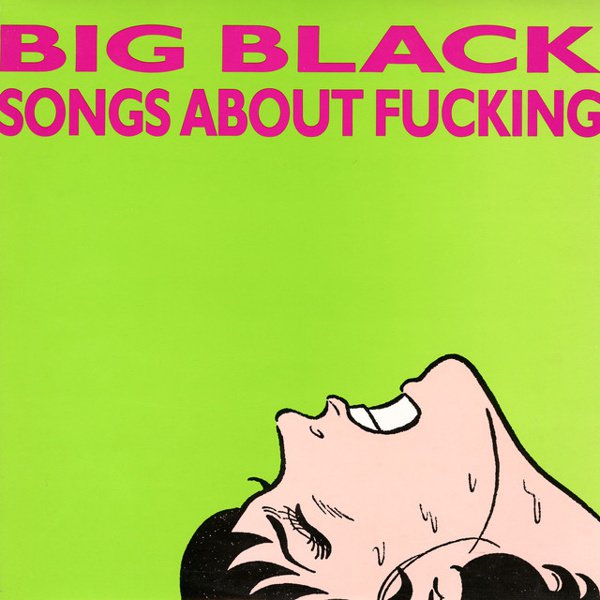

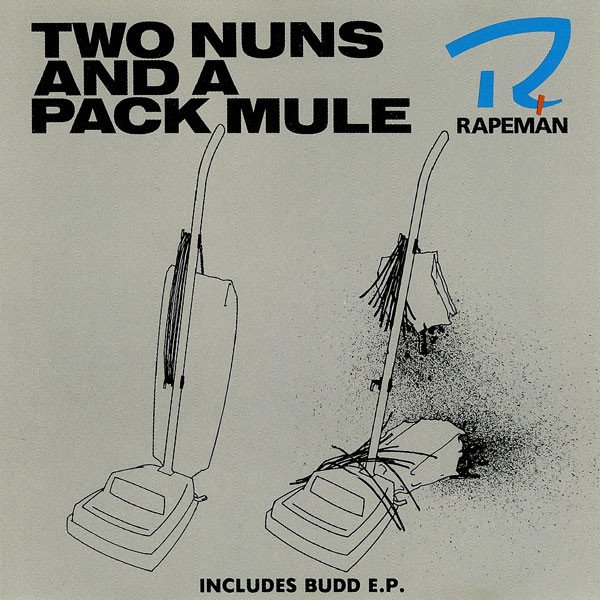

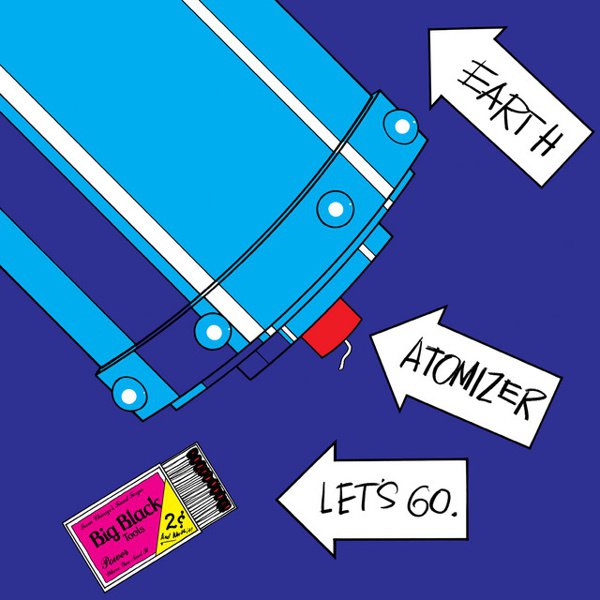

In the opinion of this writer there are five albums that best exemplify his work as an artist: Atomizer and Songs About Fucking, the two LPs he made with Big Black, the savagely caustic yet stubbornly anthemic industrial-punk act that established Albini as a true force in the 1980s underground; At Action Park and Dude Incredible, a representative pair by Shellac, the artfully severe yet slyly hilarious post-hardcore trio he formed in the early ‘90s with bassist Bob Weston and drummer Todd Trainer and that persisted for more than 30 years, up until his death; and Two Nuns and a Pack Mule, the lone full-length by Rapeman, now mostly buried due to the band’s unfortunate choice of name (which Albini later deemed “inexcusable”) but nonetheless a highly effective example of Albini’s expertise in the art of stripped-down, blackly comedic rock & roll nastiness.

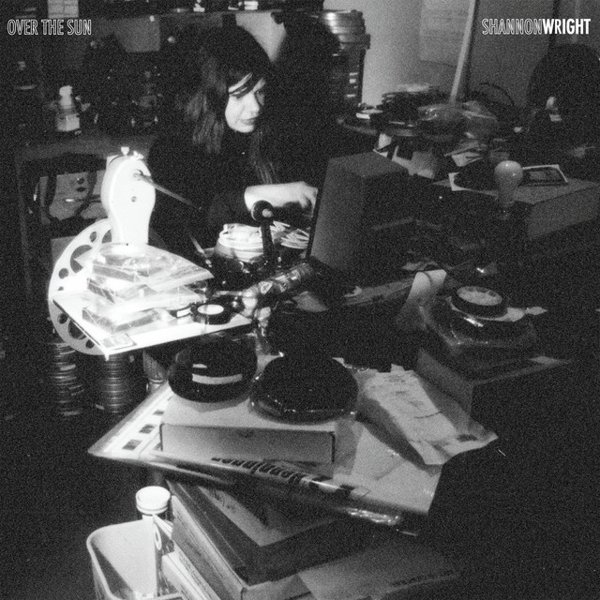

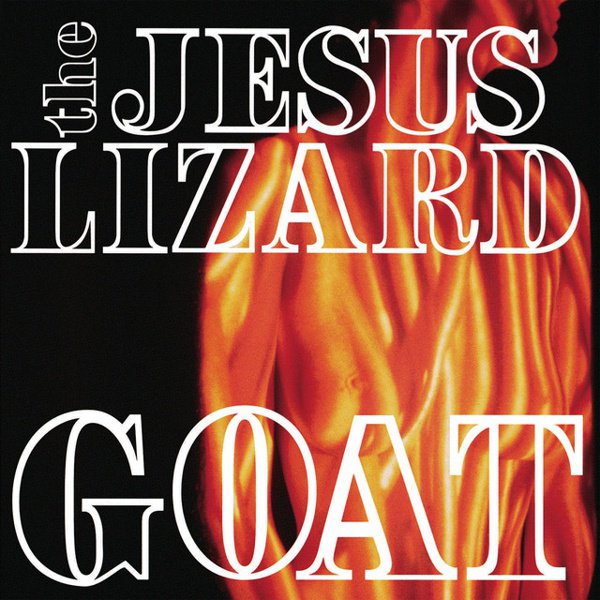

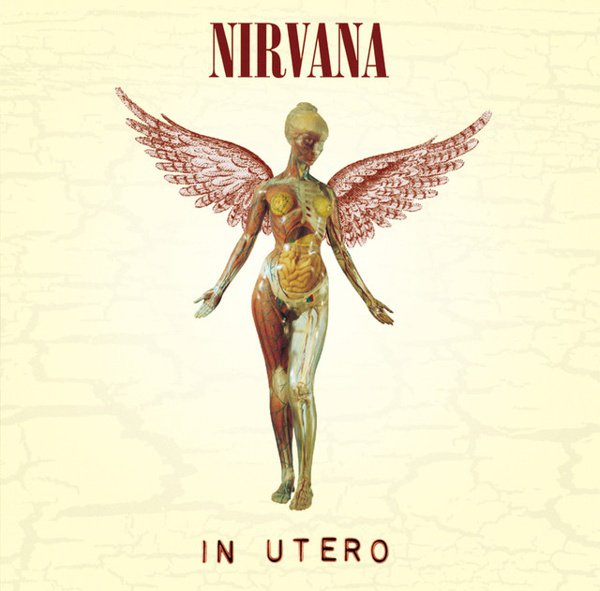

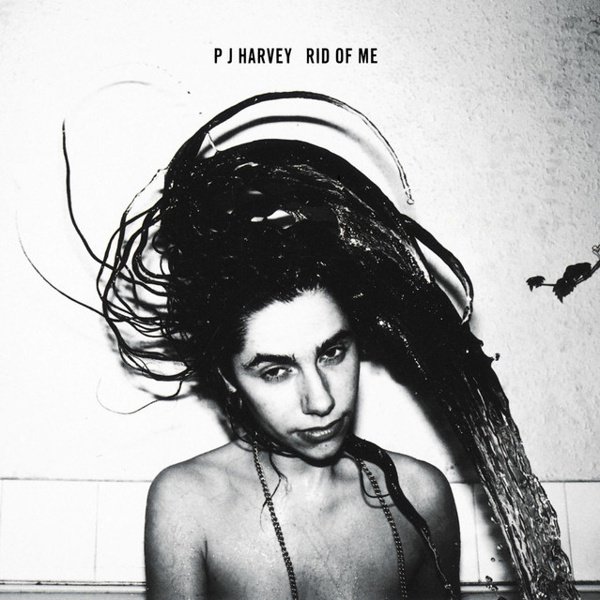

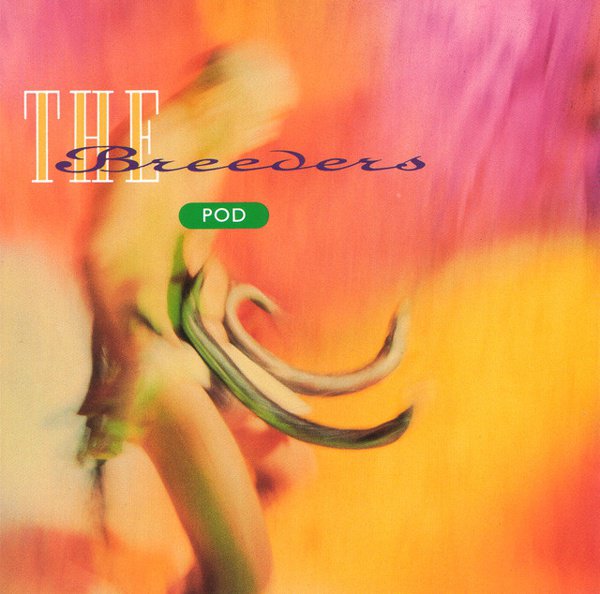

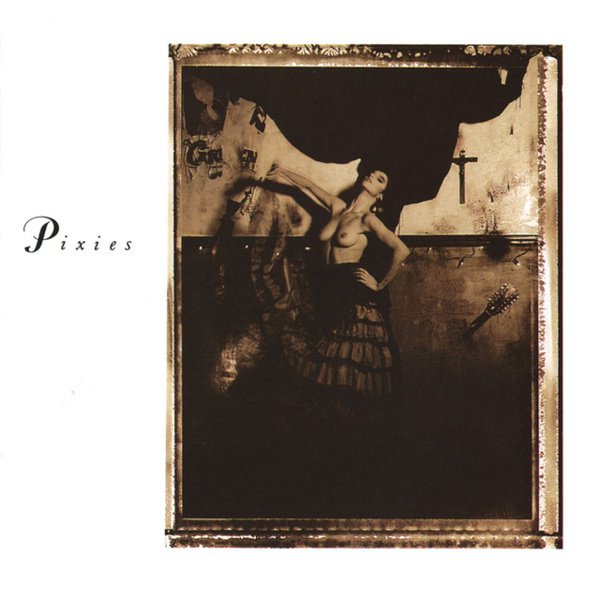

Apart from his own music, Albini’s legacy as an engineer was vast and sprawling — beyond his most celebrated, era-defining projects (Nirvana’s In Utero, Pixies’ Surfer Rosa, PJ Harvey’s Rid of Me, the Breeders’ Pod and the Jesus Lizard’s Goat), I’ve selected a few that demonstrate his surprising range and deep reach into various corners of the underground, from indie folk, art pop, instrumental grandeur and edgy singer-songwriter statements (Palace Music’s Viva Last Blues, Joanna Newsom’s Ys, Dirty Three’s Ocean Songs, Shannon Wright’s Over the Sun) to various forms of uncompromising, state-of-the-art heaviness (Zeni Geva’s Freedom Bondage, Dazzling Killmen’s Face of Collapse and Sunn O)))’s Life Metal).

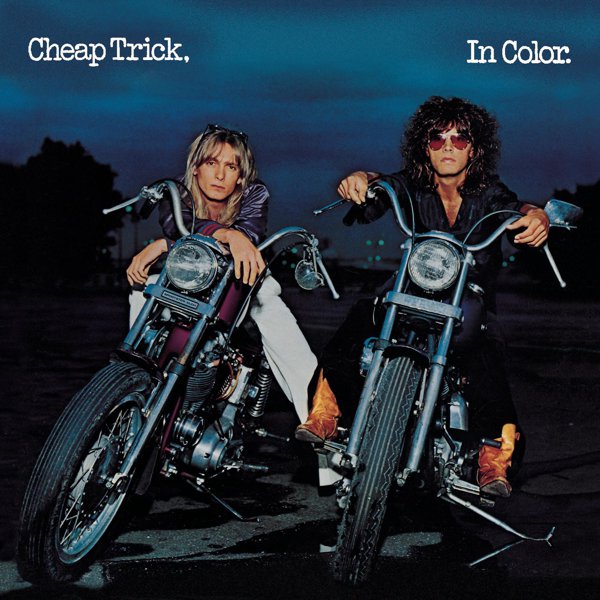

The albums that Albini tirelessly championed are crucial too. I’ve included two by key forebears and influences (Ramones’ self-titled debut, his gateway into punk rock, and Cheap Trick’s In Color, which he would eventually re-record with the band in the late ‘90s) and one by a younger band of Albini acolytes who quietly revolutionized underground rock in the early ‘90s (Slint’s Spiderland, which was recorded by fellow Chicago engineer Brian Paulson following the band’s two earlier sessions with Albini himself, and which Albini once famously designated as worthy of “ten fucking stars”).