Unlike most ‘movements’, which tend to appear far more coherent and concrete in retrospect than during their time, the development of free noise in New Zealand felt like a foregone conclusion. While you could call upon a number of historical antecedents, it really built from an extended moment of disaffection – partly, with the shift in focus of NZ’s key independent label, Flying Nun, and it surrounding ‘scene’, from documenting the underground to going for ‘hits’ and entering the belly of the beast, the corporate music industry. This led one ex-employee, Bruce Russell, to form the Xpressway label/co-operative in Dunedin in 1988, as an ideological and practical counter-movement, to document NZ’s musical underbelly. The material released by Xpressway was largely song-based (see artists like Peter Jefferies, the Terminals and Sandra Bell, for example), though it was often played with a liberatory dynamic that pointed towards what was to come.

At the same time, Russell was one third of The Dead C, notionally a rock trio, but one that had little truck with the formalities of the genre. Russell’s intractable ‘mis-competence’ when playing guitar, and his use of the guitar-amplifier nexus to channel noise and feedback, added a virulent unpredictability to the songs written by guitarist and singer Michael Morley – often, it sounds as though the two guitarists are clawing at each other, with Robbie Yeats’s drums the pacific core. As The Dead C progressed, their songs started to fall apart, and by 1993’s The Operation Of The Sonne, they’d drifted closer yet to unmoored improvisation. Russell’s musical and philosophical interests, in particular, were pushing him further and further into this terrain.

By this point, Xpressway had pretty much ended, having found international publishing outlets for most associated artists, and Russell soon started a new label, Corpus Hermeticum (H/Corp), dedicated to freely improvised music, predominantly using rock instrumentation. Russell once noted that The Dead C were “going against a very dominant cultural paradigm where the song was everything,” and the work he did with H/Corp, and his A Handful Of Dust project, extended that challenge. But I don’t want to overplay the polemical aspect – this music is exciting primarily because it was articulating unexpected ways to extend and unsettle rock’s possibilities, by drawing on models from other musics, like free jazz, collective improvisation, and electro-acoustics.

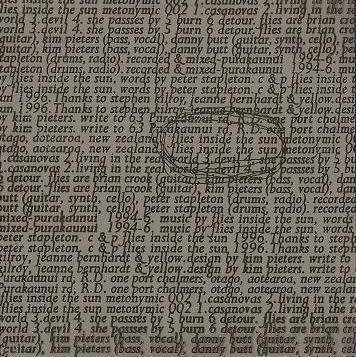

Some of the other Xpressway artists followed Russell into this terrain – Alastair Galbraith and the late Peter Stapleton (of The Terminals and Dadamah, among others) joined him in A Handful Of Dust; Stapleton would become another key player in NZ’s free noise scene, with groups like Rain and Flies Inside The Sun, and the label he co-ran with Kim Pieters, named Metonymic. But NZ free noise, in its interest in improvisation and textural exploration, and its decentering of technique and normative musicality, also drew new figures into its collective orbit, mostly from NZ’s South Island, though groups like Thela and artists like Witcyst were North Island representatives.

The artists involved were all rich with personality and creative drive: some, like Morley and Pieters, had some presence as visual artists; others, like Witcyst and Omit, were hermetic to the point of wilful obscurity. Russell’s label and its associated mail order catalogue, and writer Nick Cain’s fanzines de/create and Opprobrium, along with Simon Baker’s publication, Insample, were key nodes for dissemination, but the artists involved had also learned that there was a sizeable international audience for this music, so connections were fostered with overseas labels and mail orders like Fisheye, Fusetron, Drag City, Siltbreeze, Kranky, and Thurston Moore’s Ecstatic Peace!.

Indeed, if anyone was an international booster for the movement, it was Moore, who would talk the scene up at every opportunity. It’s no surprise given that his long-running group, Sonic Youth, were well-known both as musicians who highlighted rock’s extended possibilities – noise, improvisation, freedom – and as vocal supporters of the underground. Finding comfort in like-minded souls, NZ free noise intersected with a number of different, geographically distinct movements – in Japan, in America, in Norway, in France. And like that of their international peers, the music by each of the artists in this guide is distinctive, full of the character, ethos, and individualism of its players, covering surprisingly wide tonal and aesthetic territory. Yet it all, in the end, is informed, even if indirectly, by the playful guidelines set by Russell’s Free Noise Manifesto: “Being beyond ‘music,’ it is noise; Being beyond ‘rules’, it is free.”

There has been plenty of excellent, inspired ‘improvised sound work’ made in New Zealand since the nineties, both by these artists, and newer waves of creative souls who have found inspiration and historical context in the achievements of the nineties free noise cabal. And as discourse surrounding NZ free noise (and its local tributaries) have deepened, so has the possibility of locating precursors, like the electro-acoustic compositions of Douglas Lilburn, and the experiments of Philip Dadson’s From Scratch. But here are twenty essential albums from NZ free noise’s first flush.