When a genre of pop music undergoes one of those break-from-the-norm reactions, a splinter-group subgenre forming out of a sense of avant-garde opposition or a demand for aesthetic change, it’s usually a reaction to being shut out of the mainstream. But when hip-hop began its big underground movement in the ’90s, it seemed to happen in a counterintuitive reversal of all the Next Big Thing trends that caused sellout anxiety in punk and indie rock throughout the previous decade. Rather than a subterranean DIY movement that caught the attention of hip A&Rs itching to translate college-audience cachet into MTV “alternative rock” fodder for the masses, “alternative rap” only feels like it became that way after its initial golden era heyday seemed to have passed. Groups like A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, Arrested Development, Digable Planets, and Brand Nubian were considered stylistically bohemian and a departure from the hardcore gangsta and club-friendly pop rap that was capturing record sales and media attention, but they were still on the same labels, the same Source covers, the same blocks of Yo! MTV Raps as the likes of Naughty by Nature and UGK.

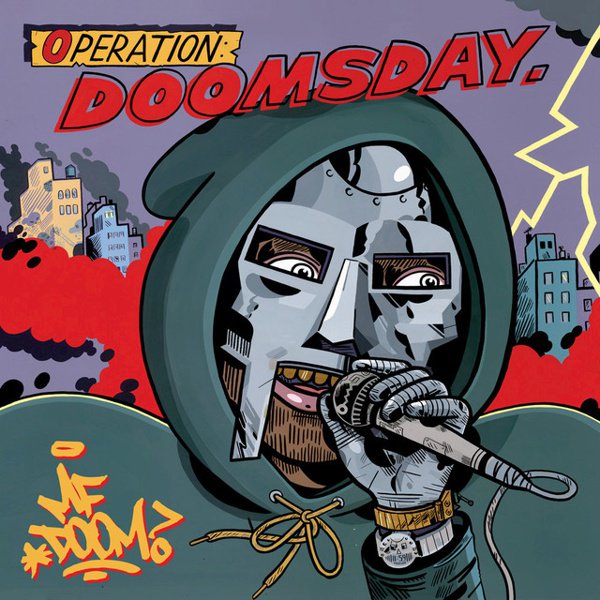

Still, something happened in the middle of the decade to put an end to all that. Sure, gangsta and pop rap moved more units, but it wasn’t just a commercial struggle: the critical and cultural battle over kayfabe versions of “street cred” and what forms of expression in hip-hop were the most supposedly true to the art form became embroiled in the idea that “alternative rap” was escapist, naive, preachy, the demonstratively wagging finger of condemnation when everyone else wanted to just throw their hands in the air. (Worst of all: it was, god help us, middle class.) So while journalists, critics, and pundits from both inside and outside the hip-hop world squabbled over the direction the increasingly eclectic and fractured art form was taking, labels started shrugging off the more ambitious artists — ones who were sometimes more artistically temperamental, and bound to a less-immediately-lucrative style that growing sample clearance costs couldn’t possibly justify. By the time the deaths of Tupac and Biggie cast the party-ending pall over the money-printing peak gangsta era of the mid ’90s, the more bohemian, more Afrocentric, and more idiosyncratic MCs and producers who’d been sidelined by that trend had broken off into an entirely different strata — one with far less exposure and fewer guarantees for stardom, but enough of a cult following to sustain careers with far more creative autonomy than any major label could even approach promising.

Pinpointing the moment this break felt most pervasive is kind of tricky. 1994 gave us Common’s “I Used to Love H.E.R.,” an early definitive expression of the “alt-rap” archetype’s disillusionment with how hip-hop lost its way in pursuit of trend-chasing and money — though Common would remain one of the few alt-rap artists of the ’90s who could go on to take his music to the majors and thrive there for at least a little while. You could also nod to shifts in label priorities — Elektra’s turn away from risky but buzzy college-audience artists after the 1994 departure of Bob Krasnow, Jive’s circa-1996 shift to teen pop, and Def Jam’s all-in investment in the Trackmasters-heavy “shiny suit” slickness that dominated 1997 all factored into the mainstream commercial downfall of alt-rap.

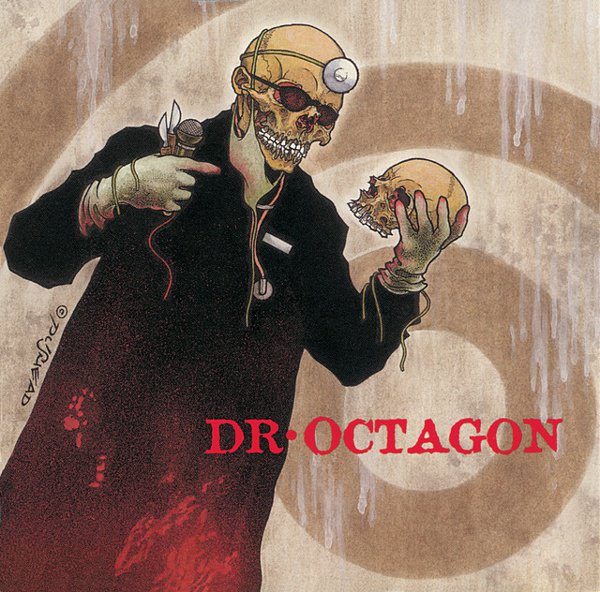

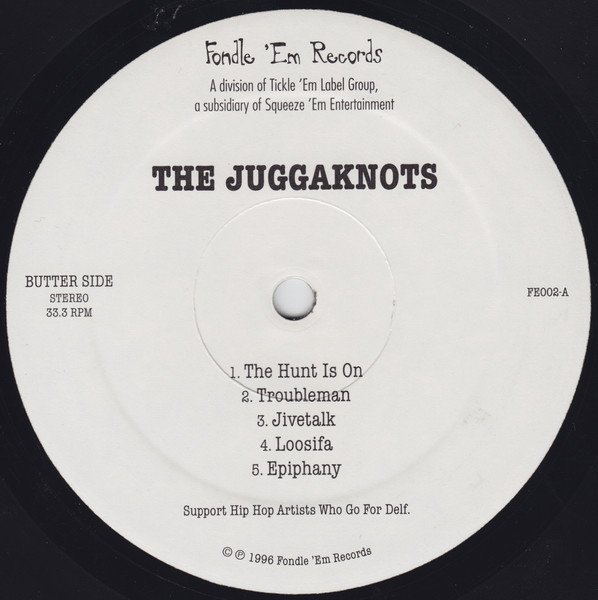

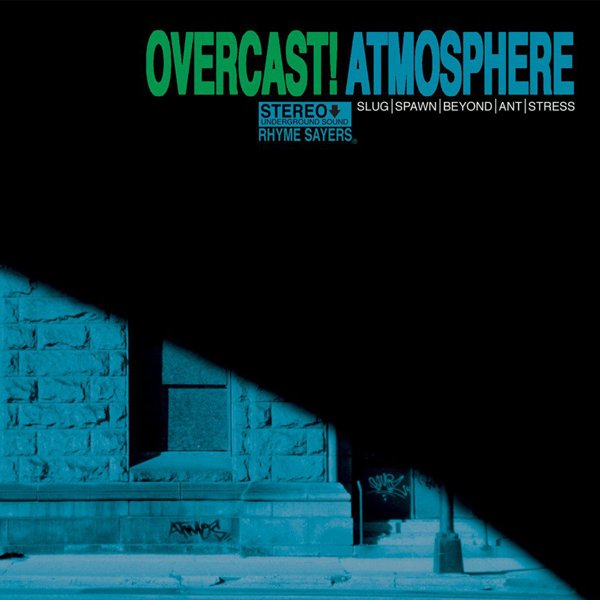

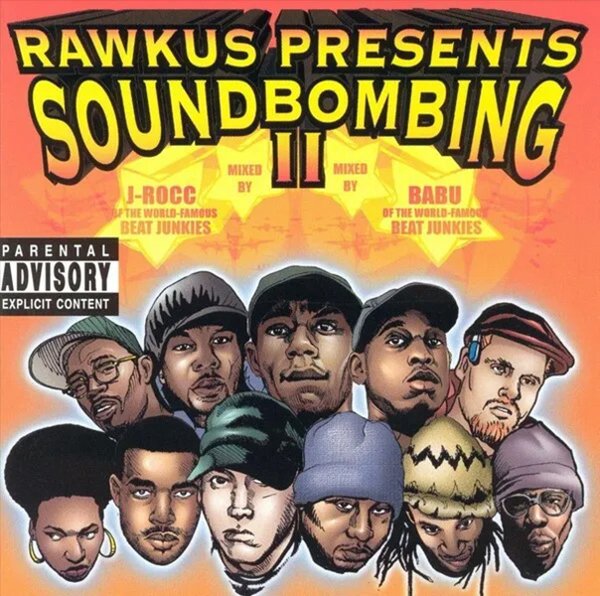

But the real shift — the reason this guide’s title uses the term Indie Rap — was the emergence, largely by necessity, of a new wave of independent labels that existed largely to pick up the artists the majors had discarded or ignored. In essence, these labels — typically with an additional focus on showcasing regional talents, like the Bay Area’s Solesides or Minneapolis’s Rhymesayers — pulled off a maneuver that looked simultaneously like the specialist roots of hip-hop’s first years on wax, and the devotion-cultivating subcultural branding that punk and indie rock labels enjoyed in the ’80s and ’90s. Sometimes the origins of these indies would vary — there’s a difference between, say, the idea of Robert “Bobbito” Garcia establishing Fondle ‘Em in ’95 as a way to showcase previously unsigned artists who killed it over The Stretch Armstrong and Bobbito Show’s airwaves, and the founding of Rawkus that same year as a sort of startup kept afloat with James Murdoch’s Fox Corp money — but as long as the artists were given (or gave themselves) free enough reign to do whatever they wanted, they could start building the foundations of a movement that would survive with or without corporate dollars — more frequently the latter.

As far as the attitudes and styles that were cultivated by this newfound autonomy on the margins, that’s a complicated tableau in itself. Even in its early stages, indie rap — or “backpacker rap” or even, sheesh, “undie” — could be socially conscious or flagrantly ignorant, built on murky lo-fi samples or live in-studio bands, lyrically poetic in ways that demand rewinds or heavy on the immediacy of slam-bang punchlines and mass-crowd-shoutalong hooks. Most of all, it navigated an unusual dual impulse of preserving and reviving the foundational elements of hip-hop while also clamoring for the advancement of the form, as if there could be a real reconciliation of back-to-the-real-shit and on-to-the-next shit. But in that sense, a lot of this music pulls off the strange sense of it being from its time, but not of it, a ’90s movement that was carried far enough into the next few decades to represent something more than just a brief rupture in the hip-hop audience. From here, you can hear the future — not the future in full, not even the majority of its sound, but enough of it to feel like this music’s more influential than the underground niches it was once confined to.