Afrofuturism is generally defined as artistic works that dare to imagine an optimistic, progressive future for African Americans through the lens of sci-fi narratives, often also throwing back to tropes of African folklore. Anyone who experienced their tender-aged years in the 1970s probably first encountered Afrofuturism through the hi-tech fantasia of Wakanda, the African homeland of Marvel superhero the Black Panther, or perhaps the rogue adventures of Lando Calrissian, mayor of the interstellar Cloud City from The Empire Strikes Back. All this while their parents soaked in the electric excursions of Miles Davis, as the jazz-fusion of Bitches Brew changed the renowned trumpeter into equal parts rock and jazz icon.

Space opera’s whitewashed world of Flash Gordon made no room for people of color throughout the 1920s and ’30s. If their radio serials and comic strips were any indication, science fiction creators must have presumed that somehow darker-skinned populations wouldn’t survive into Buck Rogers’s 25th century. The modern imaginations of Black American musicians said differently: from the discography of avant-garde jazz bandleader Sun Ra and the comic-book surrealism of funk pioneer George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic albums to the android social stratification storylines in singer Janelle Monáe’s music, the Black artists have long insisted that we survive far into the future.

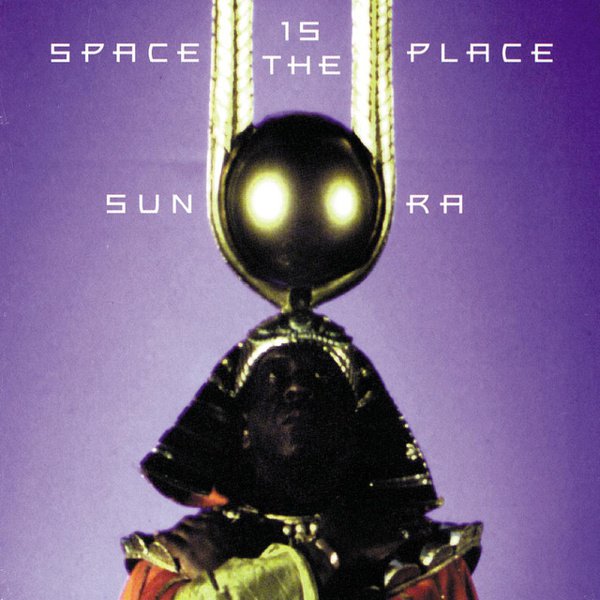

Born Herman Poole Blount a long time ago (circa 1914) in a galaxy far, far away (Birmingham, Alabama), the late experimental pianist-composer known as Sun Ra later declared the planet Saturn as his homeland—laying claim to an alien heritage that infused his songs with the first sounds in jazz that qualified as Afrofuturist. Sun Ra’s own El Saturn record label released tunes with titles like “Space Is the Place,” “Tapestry From an Asteroid,” “Space Jazz Reverie” and “Rocket Number Nine Take Off for the Planet Venus.” Releases from the Sun Ra Arkestra band musically presaged the free jazz movement of the 1960s, while ideologically infusing ancient Egyptian cosmology with a space-age orientation.

Sun Ra’s influence gleams from the ankh jewelry and Epperson fashions of singer Erykah Badu and appears in the African diaspora sci-fi of poet Saul Williams. The psychedelic, intergalactic music on Bitches Brew (represented visually by the surrealist cover art of painter Abdul Mati Klarwein) also represents an Afrofuturist jazz of its own. Pianist Herbie Hancock commanded a flying saucer from the cover of Thrust (1974), traveling sonically and spatially to worlds unknown. That through line extends over 40 years later to the album cover of The Epic (2015), Kamasi Washington’s ambitious triple-album featuring the saxophonist staring defiantly against the backdrop of two planets and all of outer space.

Afrofuturism in American popular music isn’t hard to find. Under Black Girl Nerds founder Jamie Broadnax’s definition of the movement as “the reimagining of a future filled with arts, science and technology seen through a Black lens,” DJ Grandmaster Flash’s manipulation of mixers and turntables in the early ’70s qualifies. George Clinton fused his funk music to a sci-fi mythology through P-Funk; decades later, Prince crafted a narrative on his Art Official Age that involved waking from suspended animation 45 years in the future.

In the ’70s, Clinton created a unique, signature cosmology around his funk group, Parliament, and his psychedelic black rock band, Funkadelic. The cornerstone concept of African Americans in outer space was central to the P-Funk mythos, evidenced by the group erecting a 20-foot, 1,200-pound flying saucer on nationwide concert stages. (The spaceship currently sits docked in a hallowed hall of Washington D.C.’s “black Smithsonian,” aka the National Museum of African American History and Culture). Clinton’s alien alter ego, Star Child, and both groups’ futuristic costuming, cover artwork and science fiction themes, make Parliament-Funkadelic a base component of Afrofuturism.

David Bowie ushered in glam rock as interstellar rock star Ziggy Stardust, with all the makeup, wigs and outrageous costuming that entailed. Then he moved on. But visionary designer Larry Legaspi moved on too: outfitting KISS, as well as the Afrofuturist fashion of P-Funk and the female rock-soul trio of Labelle. Patti LaBelle, Nona Hendryx and Sarah Dash opened for the Who and the Rolling Stones sporting silver spacesuit couture and glittery cosmetics, singing songs like “Space Children” and “Cosmic Dancer.”

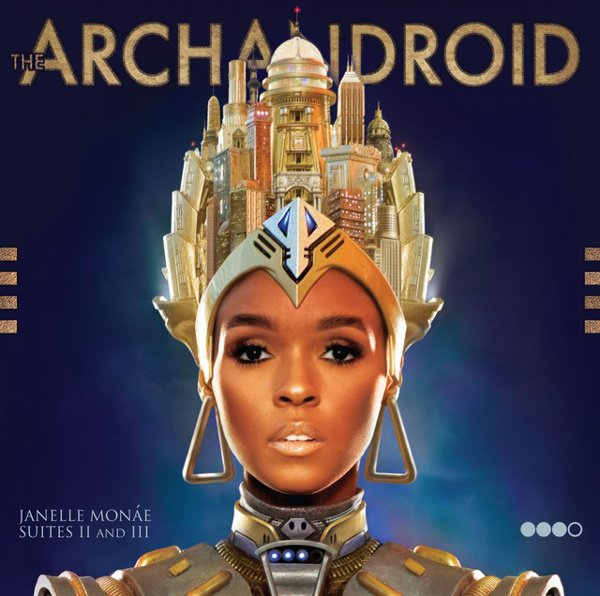

Janelle Monáe called her 2018 short film, Dirty Computer, an “emotion picture.” Exploring concepts of womanism, gender fluidity and identity, Monáe cast herself as Jane 57821 in a totalitarian, dystopian society reminiscent of THX 1138—but with Black folks displaying an open sexuality. The Grammy-nominated record that this visual album stems from caps a career full of Afrofuturistic concepts, like Monáe’s cyber alter ego Cyndi Mayweather, and the Octavia Butler-esque backstory underlining The ArchAndroid and Metropolis: The Chase Suite.

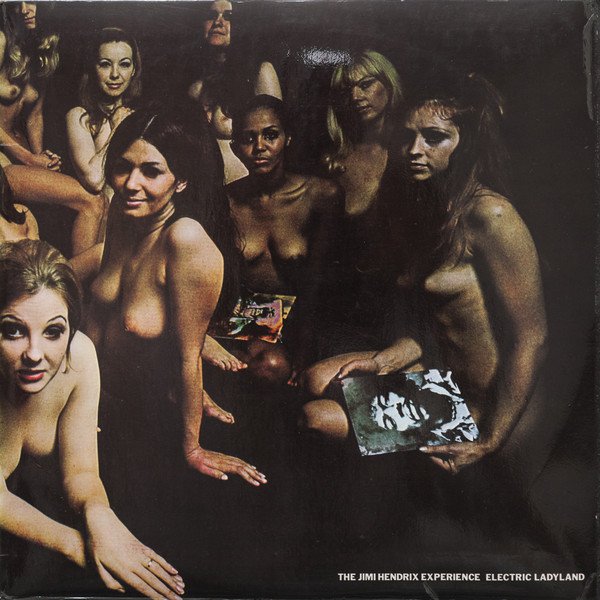

The resistance initially raised against Black-invented music genres like jazz, rock ’n’ roll and hip-hop (all of which were later embraced and subsumed into mainstream culture) happened because those music forms were innovative, cutting edge, ahead of the times in which they were created. Afrofuturistic, in other words. The unique struggles of Black life have always necessitated a lean forward into a future in which white supremacist ideals might be eliminated. The music—from the squealing guitar feedback of Jimi Hendrix to the off-kilter time signatures of Dilla—has always reflected that. The following artists’ work all bring the promise of Afrofuturist music to fruition, simultaneously celebrating the past while focused on the far-flung future like sonic Sankofa birds.