“Bubblegum is the naked truth,” as the 1968 compilation album, and subsequent (unassociated) book about the genre, has it. I’ve always appreciated the sentiment as a snook cocked at dominant cultural wisdom about sincerity, value, and authenticity. Of course, now we’ve lived through the days of poptimism, and research fields like cultural studies have helped us dismantle misguided divisions between high and low culture, while recognising the ongoing social sedimentation of such hierarchies, things don’t look quite so clear-cut. But the truth of bubblegum music prevails – pop music can be featherlight and yet pack a deep emotional punch; pleasure, joy and frivolity can tell us more about the world around us than emotionally eviscerating torch songs, ponderous prog rock, or indeed, pop-psychology textbooks.

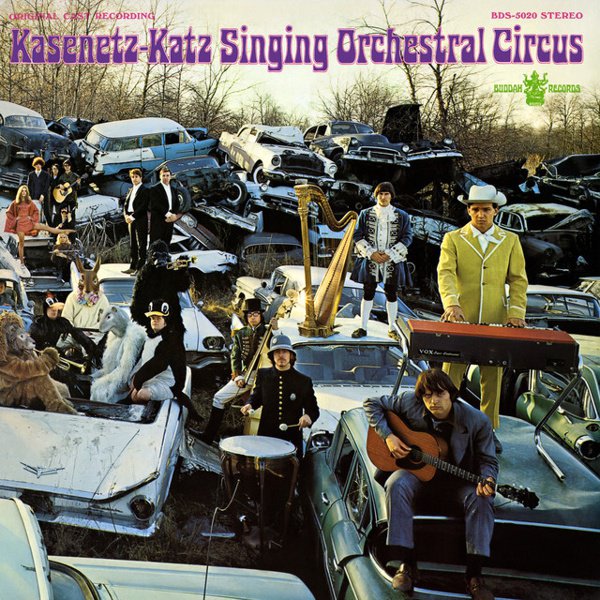

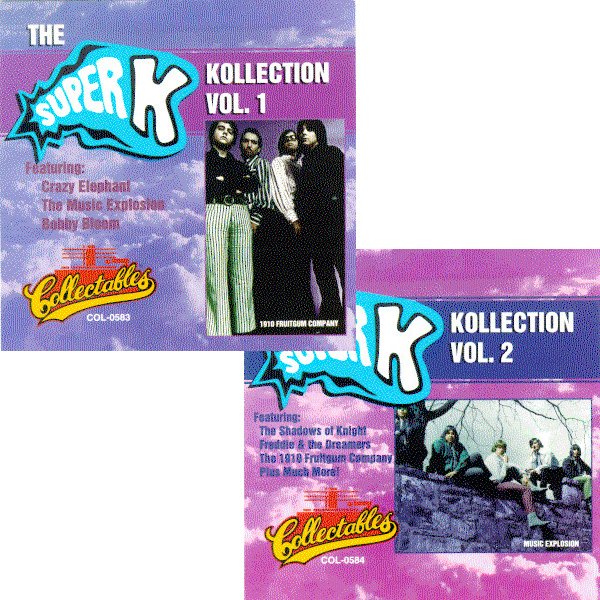

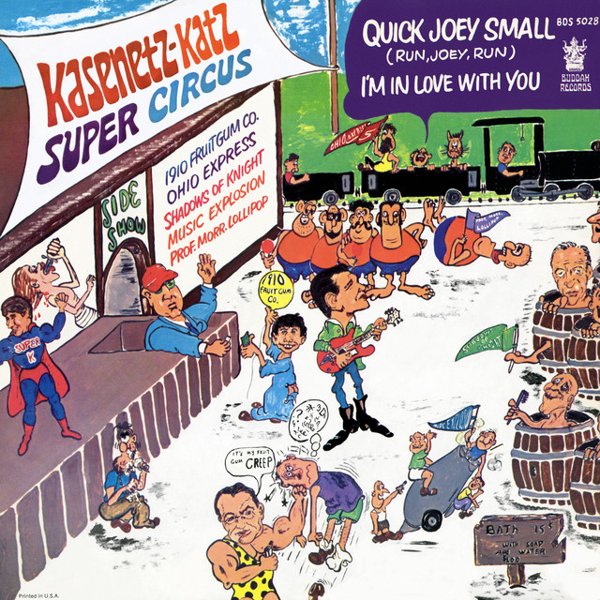

The creation of bubblegum music as a genre can ultimately be traced back to two American producer-songwriters, Jerry Kasenetz and Jeffry Katz, whose Super K production house is the historical home of the bubblegum ethos. In their wish to enchant a teenage audience, they harboured a mind’s-eye view of the average teen, listening to their radio while chewing gum, and had the revelation: “Ah, this is like bubblegum music.” In this respect, bubblegum music goes hand-in-hand with the invention of the teenager as consumer category, their post-World War II boomtime creation as an audience to be relentlessly targeted with commodities as tools of identity construction.

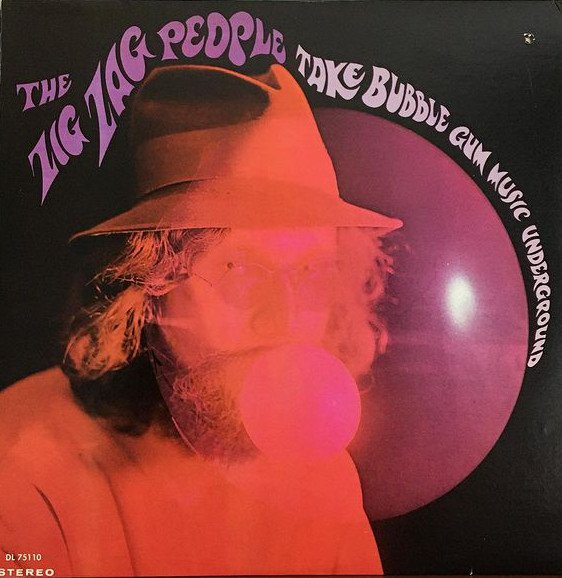

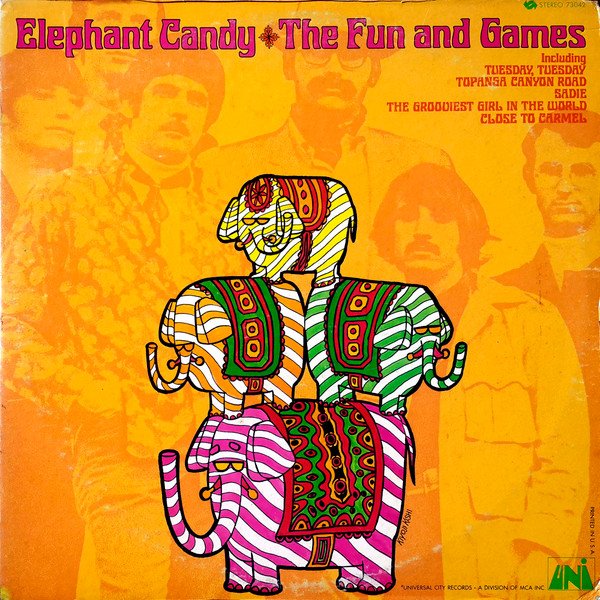

But bubblegum music somehow came to mean more than just that. In its creative voraciousness, it chewed up and spat out the music that surrounded it: in these songs, on these records, you can hear the spirit of the Beatles, the Kinks, the Beach Boys, and so many more, all placed in service of an ultimate pop spirit that drifted, in most welcome fashion, from the songwriter-auteur stylisation that was being developed by record companies, PR spin and a nascent rock music press. The point of this music was that it was sweet, sugary, a shot of glucose – feverishly fun, yet disposable in its design. That it has lasted, in certain record collector subcultures and music fandoms, tells us much about the way aesthetic disposability develops its own legacies.

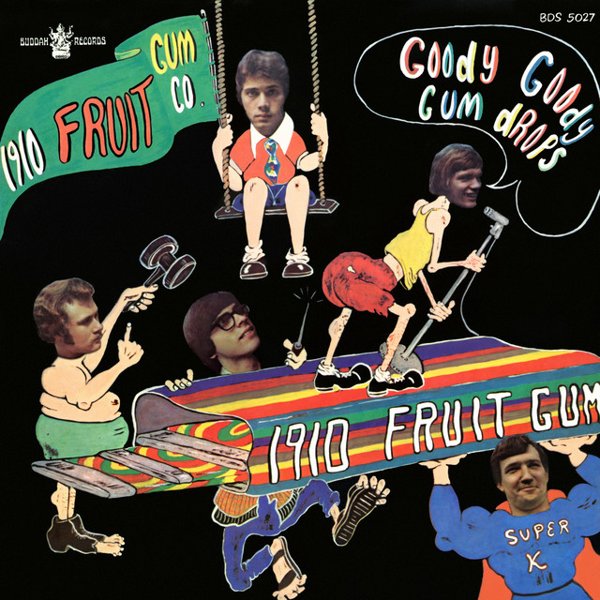

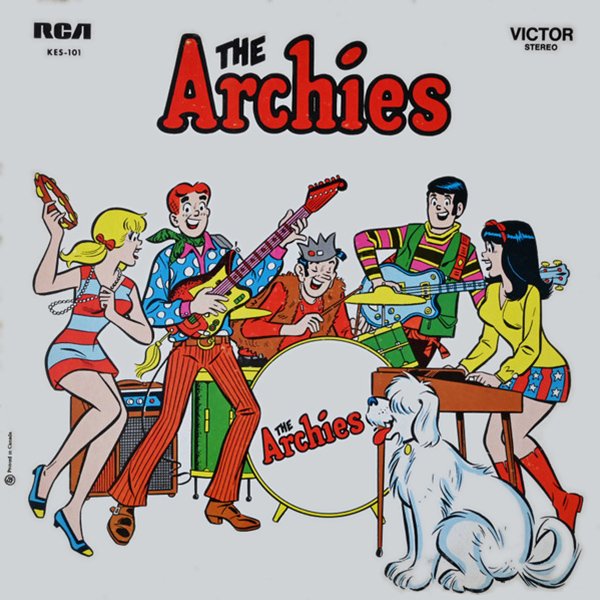

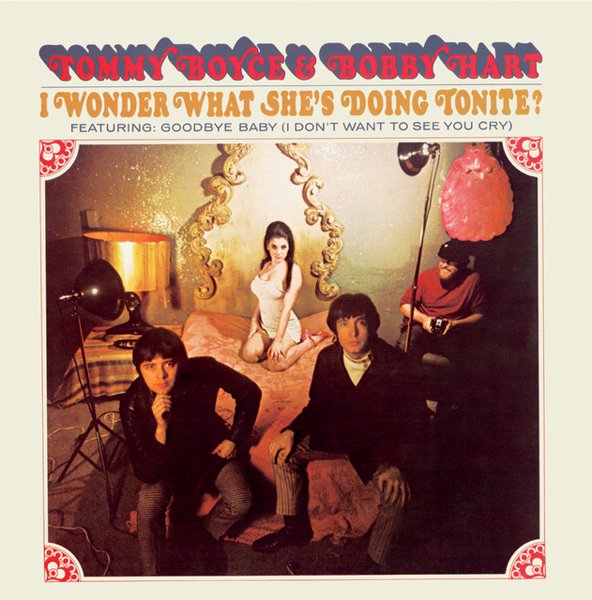

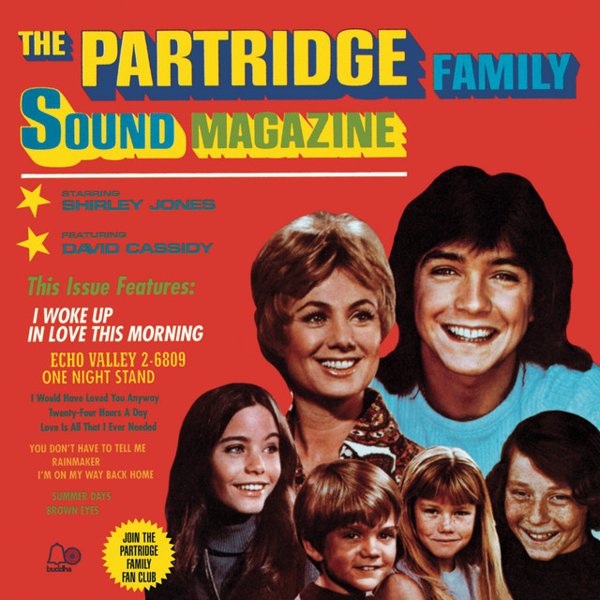

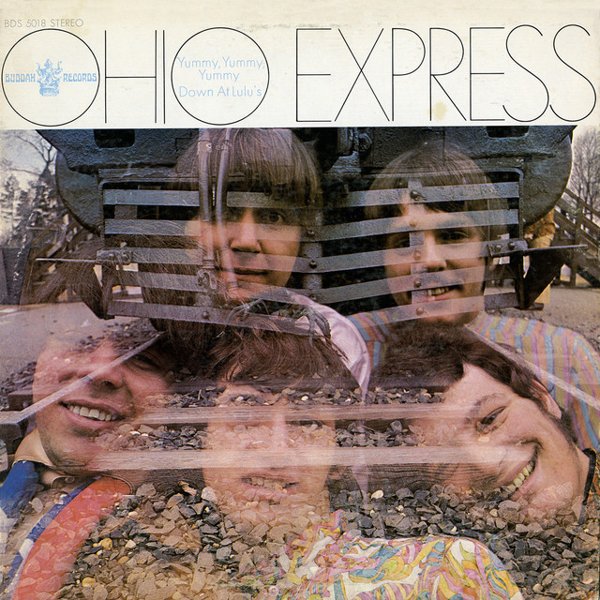

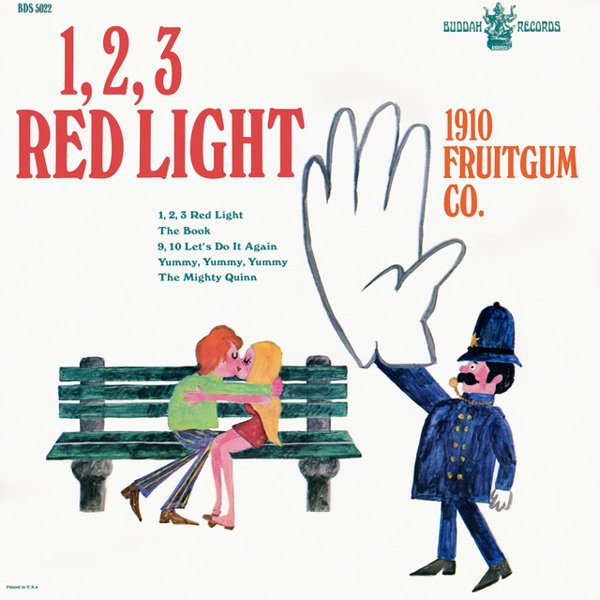

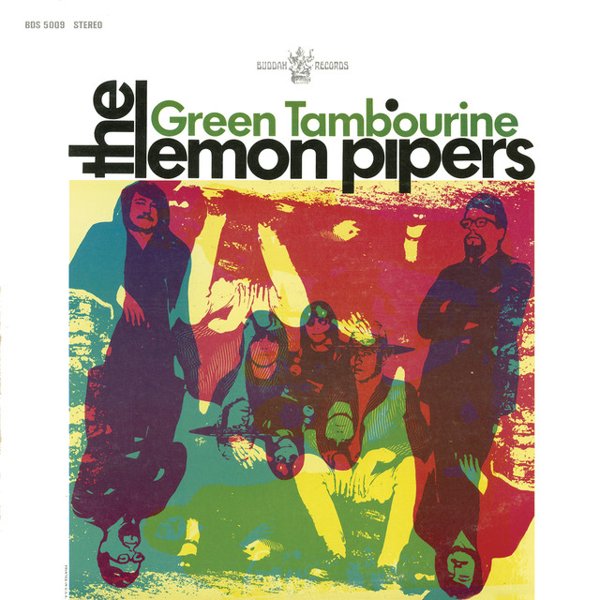

There were, of course, many more figures involved in bubblegum in its late sixties heyday. There are creative and industrial figures like Joey Levine, Tommy Boyce, Bobby Hart, and Neil Bogart, and labels like Buddah and Kama Sutra. There are media crossovers, like television shows for The Monkees (whose position in the bubblegum firmament is contentious), The Archies and The Banana Splits. There are also genre crossovers – there’s a clear through-line from garage pop and rock, the sound of amped-up teenagers getting loud and rowdy in the basement, to bubblegum’s “keep it simple, stupid” designs. And there are relationships between sunshine pop, psychedelic pop (or pop sike) and bubblegum that can sometimes be hard to track.

I guess one of the things that distinguishes bubblegum from other genres is mercenary intent. The producers and writers, and some of the musicians no doubt, were there to make a quick buck. But there is an aesthetic at play here, which pushes a song’s essential pop core to the forefront; instrumentation that’s generally rudimentary, with simple yet dynamic chord changes; sometimes, if you’re lucky, you’ll get some production flourishes, particularly on the more ‘sunshine pop’ end of things (who tended to love their baroque and rococo stylings).

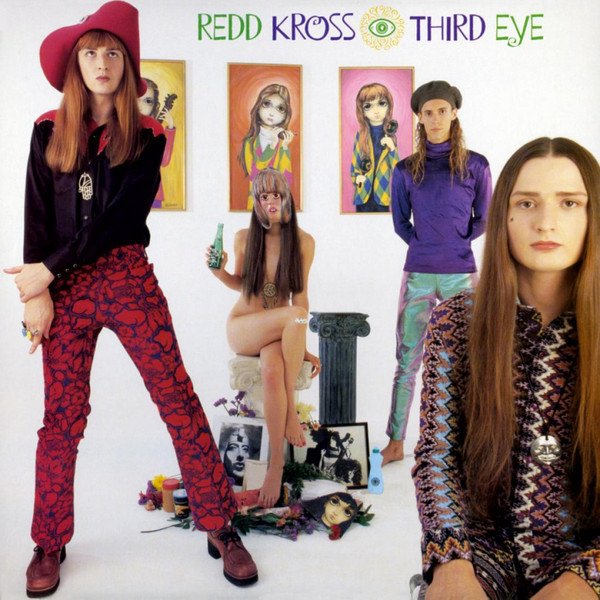

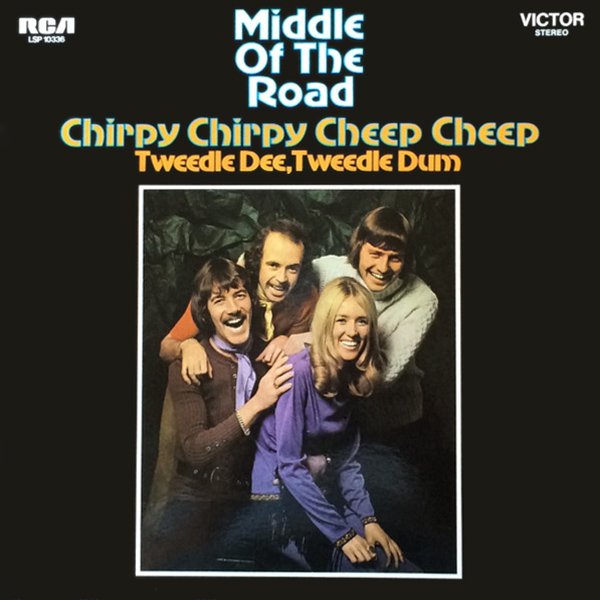

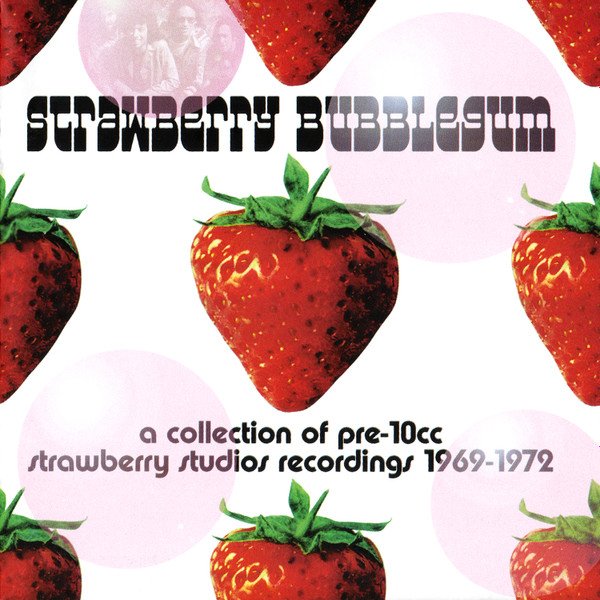

Bubblegum, at its core, tends to be thought an American phenomenon. If it happened in Britain and elsewhere, it was derived in some way from the ethos of production houses like Super K, in an either overt or covert way. In the early seventies, a wave of bubblegum-esque pop emerged from Britain (Middle of the Road, Lieutenant Pigeon) but that material, in my mind, has some kind of loose connection with glam and its ‘junkshop glam’ sub-genre. And if this list focuses on that sixties heyday, with a few gestures toward bubblegum’s uptake by underground artists, that’s a function of space more than anything: you could trace another line through to teen pop like Britney, artists like Charli XCX, even k-pop.

The other curious thing here is thinking of bubblegum as an albums genre, when so much of the music made its way into the world as seven-inch singles, one two-to-three minute pop injection after another. Yet the albums are intriguing in their oft-identikit formation (much like garage punkers The Seeds, come to think of it) and some of the compilations are brilliant collections of pop genius. Bubblegum, and neighbouring genres like sixties teen pop and girl pop, also has its own network of reissue labels and dedicated boosters.

On a personal note, I find this music endlessly intriguing, fascinating, and joyous. In its seeming lack of guard and guile, it somehow tells us just as much, if not more, about its times than the quote-unquote profound rock and pop music that has come to stand for the late sixties and early seventies in much music crit discourse. However, it’s not reducible to some kind of rockist/poptimist dialectic. In my (perhaps addled) mind, Kasenetz-Katz or Joey Levine aren’t the dialectical opposite of Bob Dylan or Joni Mitchell – they simply stand proud and smart alongside such figures as indices of the great art that help create and sustain their times. Their cultural savvy might have been applied to different means and ends, but they still battled in the marketplace of ideas, and they landed some significant blows (anyone, like me, who can sing The Archies “Sugar Sugar” in their head from beginning to end will know what I’m talking about).

I’ve not come to rush to bubblegum’s defence, but rather to celebrate its unquestionable genius.