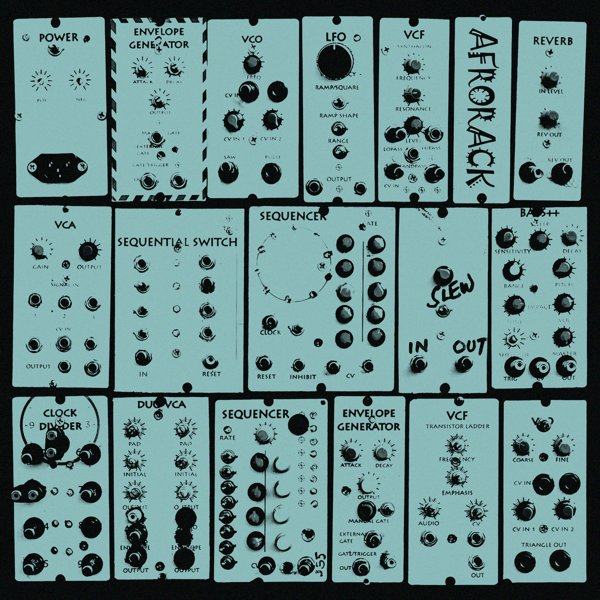

Synthesizers have been a great driver of the evolution of African music, but when they first appeared on the continent these expensive new technologies were only available to a select few. Great Nigerian synth experimental artist William Onyeabor for example was reportedly a rich businessman who owned his own recording studio and pressing plant, while Nigerien composer Mammane Sani was able to meet people from all over the world through his work in UNESCO and bought his first “Orlo” organ from an Italian colleague. Other artists, like Francis Bebey and Hailu Mergia, only started experimenting with synthesizers after moving abroad.

Gradually though, as synths became cheaper and more widely available, their glitzy, futuristic sounds started to bleed into pop music all over the continent, from South Africa’s Bubblegum to Somalia’s electro-funk. But it wasn’t until recently, as synths evolved from analog to digital and finally to computer software synths, that kids in all corners of Africa — like in the rest of the world — have been able to make music using just a computer and free production software. Not only that, but music can now easily be shared all over the globe.

These new dynamics of music production and consumption epitomize what DJ and writer Jace Clayton calls “World Music 2.0”: “There’s this unprecedented, amazing growth of musical activity all over the globe. It’s a fascinating mix of hyper-localized music and global sharing” he explains in his book, Uproot: Travels in 21st-century Music and Digital Culture.

On the one hand these developments mean that African musicians are increasingly connected to global music networks, and no longer have to rely on gatekeepers (like promoters or record companies) in order to share their music. The Nairobian collective EA Wave for example learned how to make music using “the college of Youtube,” and the five members were able to connect to other artists around the world through social media. Their music is an amalgamation of global influences and local sounds, bringing together anything from airy synth pads to 808s, African percussion and jazzy samples. Access to free production software and sharing platforms, they explain, has given them the freedom to define their own identity without abiding to stereotypes of what “African music” should sound like. “My music is African by virtue of me being African,” says Ukweli, one of the members of EA Wave.

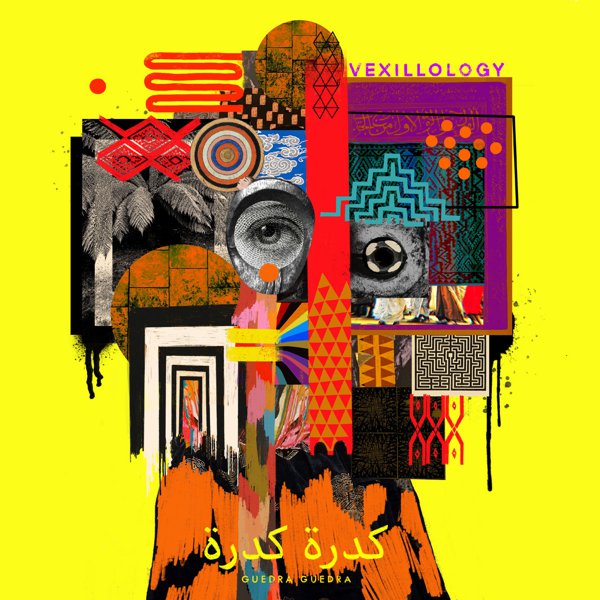

On the other hand, while the general transition from analog to digital has enabled greater cross-pollination between African music and sounds from all over the world, it also serves as a way for musicians to preserve traditional music and ensure that it lives in the present. As fewer people are playing traditional instruments and hiring traditional bands to play events has become more expensive, local producers are recreating traditional sounds by using drum machines, synths, and software like Fruity Loops. In Bamako, Mali, starting in the 1990s DJs began replacing expensive Balafon troupes at social gatherings with recorded tapes of Balafon or Coupé-décalé music while playing drum pads and synthesizers alongside them, and these “Balani Shows” are still an important part of the city’s street culture. In northern Uganda synths and computers have replaced traditional Acholi instruments, giving birth to the Electro Acholi sound, while in northern Ghana producers like Francis Ayamga are reinterpreting the traditional Fra Fra sound by incorporating electronic production into traditional acoustic performances. In all corners of the continent, even in remote areas, there are thriving electronic scenes that are rooted in traditional sounds.

Many cities too have their own vibrant electronic music scenes (Accra-based Oroko Radio is a great place to hear contemporary music from all corners of the continent): in Addis Ababa, artists like Mikael Seifu and Endeguena Mulu, aka Ethiopian Records, have contributed to the rise of “Ethiopiyawi electronic” by merging traditional Ethiopian music with electronic production; Dakar boasts a bubbling and fast evolving creative scene, which Dakarois electronic music pioneer Ibaaku recently paid homage to on Neo Dakar Vol.1 and Neo Dakar Vol.2; and in Nairobi, alongside the more global sounds of artists like EA Wave, local genres like SHRAP (Sheng + Trap + Pop) and Gengetone (Kenyan Pop) are thriving.

But thanks to growing global connections, diaspora networks, and the development of local music scenes and recording industries, African electronic music is becoming increasingly ubiquitous on dancefloors all over the world. Nyege Nyege has done a great job at “exporting” hyperlocal electronic styles like Electro Acholi or the frenetic Tanzanian Singeli Sound, and in summer 2022 there are few European festivals that don’t feature at least one Nyege Nyege DJ or MC in their lineup. Gafacci has emerged from the underground Accra scene and is quickly becoming a global clubbing phenomenon, while KMRU is widely regarded as one of the most exciting ambient artists of the last few years.

But by far the biggest African sound on dancefloors at the moment is amapiano, which emerged in the townships of Johannesburg and Pretoria around 2012 and has conquered the world with its log-drum percussion, jazz-inflected keys, kwaito-like basslines, and its euphoric, bright synths.

A lot has changed since synthesizers were first integrated into African music, but it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that their impact has been revolutionary. Technology has evolved from big, expensive analog synthesizers to cheaper digital ones, all the way to production software like FL Studio that enable producers to sample all kinds of instruments, meaning that synths are now at anyone’s fingertips as long as they have a laptop and electricity. This “democratization” of musical technologies, the fact they are available to almost anyone and are being incorporated into an enormous variety of different musical traditions, or aiding in the development of new ones, is giving birth to some truly exhilarating music.