The story of synths in Africa is primarily one of movement — of people, instruments, and sounds. It’s also a story of resourcefulness and experimentation, driven by social and economic changes, lack of infrastructure, and, in some cases, unexpected fortune: the sudden influx of money, music, and access to new technologies.

The tale of how synths first got to the continent starts with a touch of fantasy: According to a story told by the label Analog Africa on the occasion of the release of their fantastic compilation Space Echo — The Mystery Behind the Cosmic Sound of Cabo Verde Finally Revealed!, in the late 1960s a mysterious ship appeared on the Sao Nicolau island of Cabo Verde, far away from the coastline, as if it had fallen from the sky. After Portuguese colonial authorities had conducted their investigations, the villagers opened the containers to find piles of machinery they’d never seen before: synthesizers. According to Analog Africa, anti-colonial leader Amílcar Cabral ordered for the instruments to be distributed to islanders who had access to electricity, including schools, and the children who grew up experimenting with the new equipment would go on to become the islands’ great musicians, modernizing local styles like Funaná, Mornas, and Coladeras. Though it makes for a great story (and even greater music), there is likely more than a touch of embellishment here, and synths likely didn’t reach the islands until a few years later (and probably in a more conventional manner).

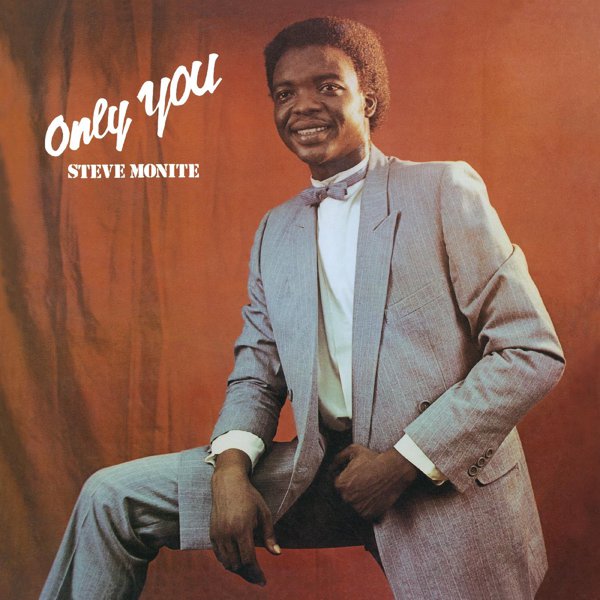

In other parts of the continent synths arrived in less fantastical but still meandering ways. According to Nigerian writer and scholar Uchenna Ikonne everything changed in Nigerian music when, in 1975, Jimmy Cliff was forced to leave his equipment behind after an African tour due to problems at customs. For a while these ultra-modern synths and amps languished in the EMI studios, but soon started popping up in their newest productions, kickstarting a move away from band-led highlife and afrobeat and towards a new craze for the synth-led disco and boogie sounds.

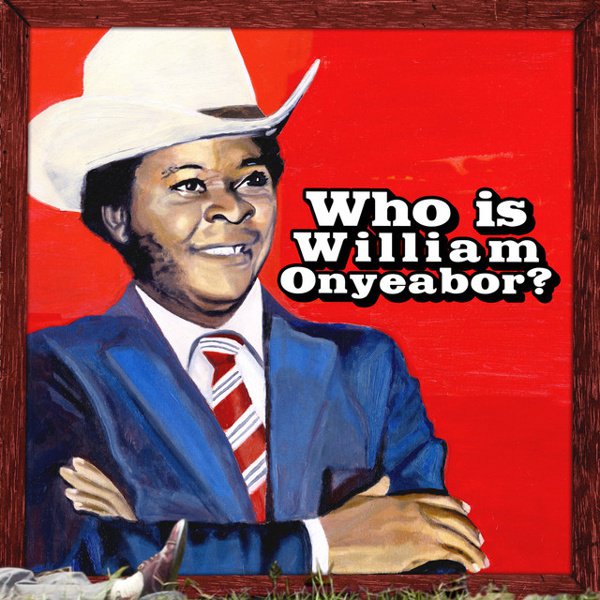

With the economy booming, throughout the 1970s and 80s independent labels and state-of-the-art studios like Phonodisc and Ginger Baker’s Arc flourished and artists became increasingly experimental with the new technologies. No one pushed them further than visionary synth wizard William Onyeabor, who, rather than using synths to recreate the sounds previously made by instruments, made music that didn’t owe anything to tradition.

While the Nigerian music scene thrived, in nearby Ghana the situation could not have been more different. A series of dictatorships and prohibitive import taxes on musical instruments all but killed the once vibrant music scene, and musicians started leaving Ghana for Europe. One of the first was legendary highlife musician Pat Thomas (although his motivations were less financial and more romantic) whose style quickly evolved from more traditional instrumental highlife to a new modern and international sound that merged West African melodies with disco, boogie, and funk with the use of DX7 synthesizers and drum machines. Thomas was one of the early pioneers of “burger highlife”, the diasporic sound created by Ghanaian immigrants in Germany and other parts of Europe and spearheaded by George Darko with his 1982 album Friends.

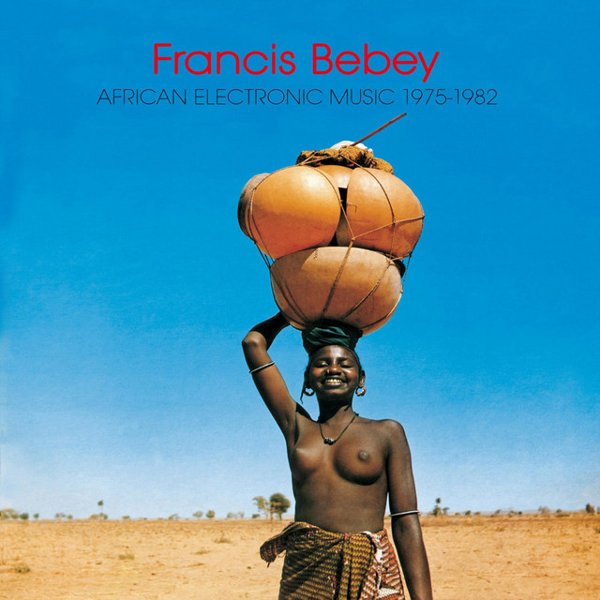

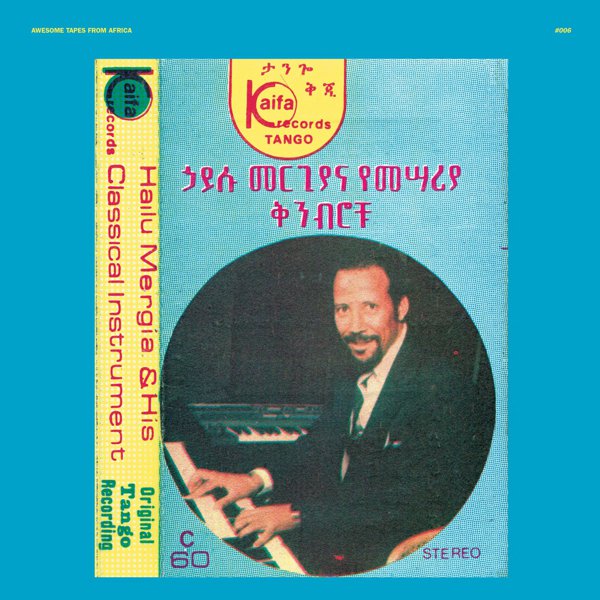

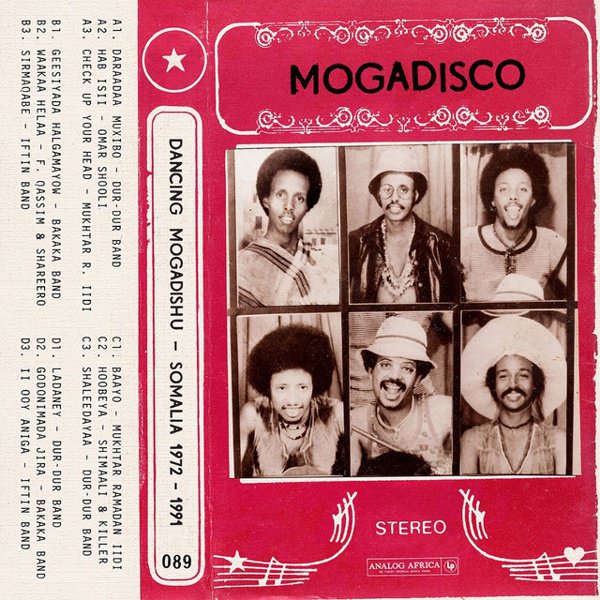

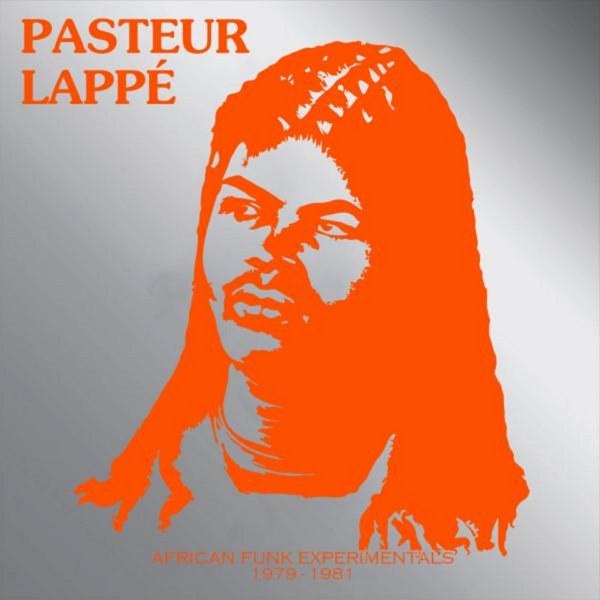

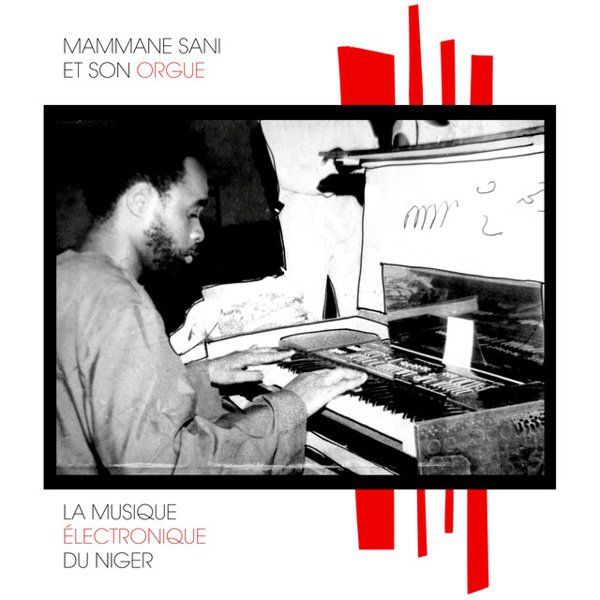

Just like the Ghanians in Germany (and those back home who wanted to emulate their modern new style), musicians all over the continent experimented with these new technologies, in many cases maintaining traditional melodies and scales but with an ear to developments in other parts of the world. In Cameroon Francis Bebey placed synthesizers and drum machines alongside traditional African instruments; In Somalia, bands like Iftin and Waaberi began using synths in their tracks, fostering a “Golden Era” of Somali music; just over the border, Ethiopian musician Hailu Mergia played his old accordion alongside a Rhodes piano, synthesizer, and drum machine on his 1985 record Hailu Mergia & His Classical Instrument, creating a sound that is at once evocative and futuristic. In Kenya many bands imitated the slick sounds of American disco, but in some cases experimented with more local electro hybrids, such as in the case of African Vibration’s mijikenda track Hinde.

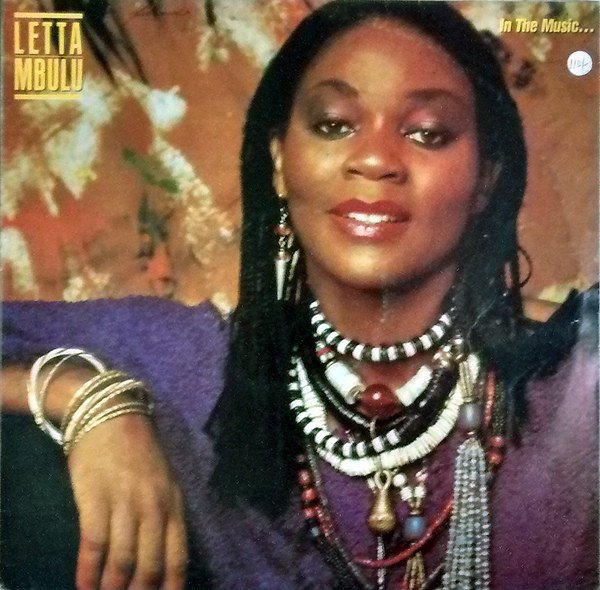

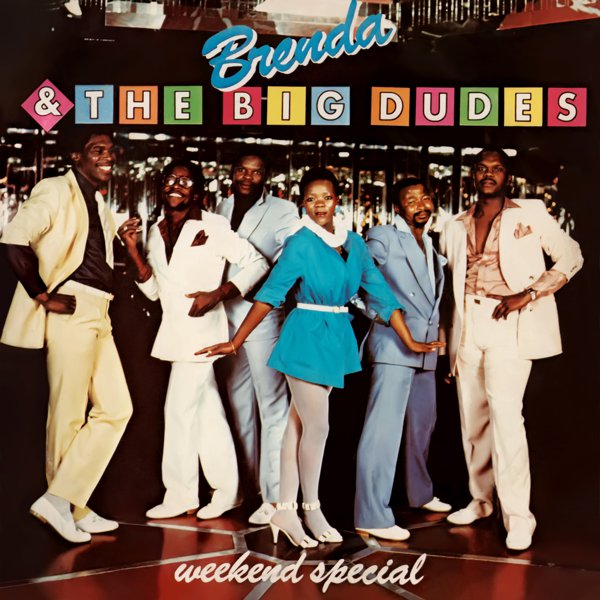

But nowhere did the arrival of synthesizers have as much of a widespread impact as in South Africa, a country still in the violent grip of apartheid segregation and discrimination. Despite the socio-political situation, the airwaves were filled with the joyous grooves of bubblegum music, which was pioneered by the likes of Brenda Fassie and Sello “Chicco” Twala and merged synths, keyboards, drum machines and soulful vocals with typically South African harmonies and melodies. Outwardly frivolous and fun, bubblegum’s appeal overcame the racial divide and quickly became a political battleground, with musicians openly including anti-apartheid and pro-Mandela messages in their music.

Bubblegum reigned throughout the 1980s, but as apartheid ended so did bubblegum’s popularity. Music became increasingly electronic and dance focused, and Kwaito emerged as the expression of South Africa’s new-found freedom, combining the sound of mbaqanga with simple percussion loops, bright synth stabs (the Korg M1 was especially popular), and rapped vocals. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s shangaan disco, pantsula, Bacardi House, gqom, and most recently amapiano, emerged as new music and dance styles in South Africa.

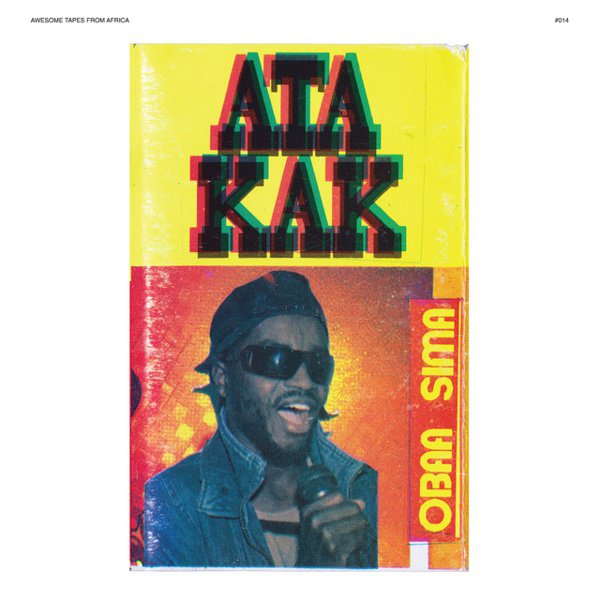

All over the continent 1980s synth music has evolved into countless new sounds as synthesizers, computers, and programs like Fruity Loops have become more widely available. In some cases these new musical technologies have fostered the emergence of homegrown, localized electronic scenes rooted in traditional sounds, such as the electroacholi scene of Northern Uganda or modern Fra Fra music in northern Ghana. At the same time a growing number of African producers are making techno, trap, and house music, inspired by sounds from outside the continent (and vice versa, as the internet has made this exchange much easier). Today, in all its forms, African electronic music is as exciting and vibrant as ever.