The loft jazz scene, as its name indicates, was as much about economics (and the New York real estate market) as music; the two evolved side by side. Two deaths marked major transition points for the avant-garde jazz community. In July 1967, John Coltrane died of liver cancer, and in November 1970, Albert Ayler’s body was found in the East River. Coltrane’s wholehearted embrace of free jazz in his final years, which included getting Ayler, Archie Shepp and Pharoah Sanders signed to Impulse! Records, had brought a great deal of attention to the music, but also solidified its image in many minds: to the average person, it was all about assaulting the listener with endless screaming horn solos, angry poetry, and oceans of percussion. Ayler had embraced rock and gospel in his final years, alienating some listeners but never losing the intensity that had marked his work since the beginning.

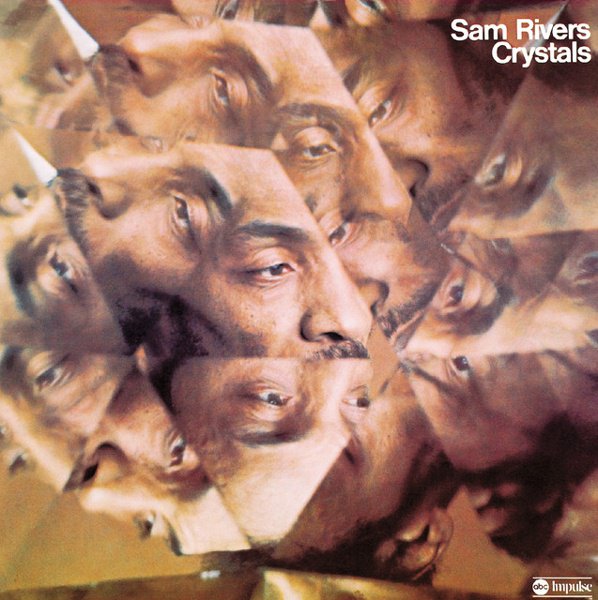

With these two tenor titans gone, the music seemed to draw in on itself, becoming more introspective and experimental, just as the overall economy of New York City took a tumble. (By the middle of the decade, the city was on the brink of bankruptcy.) Real estate was dirt cheap, and actual jazz clubs didn’t like booking free/avant-garde players, so some musicians took matters into their own hands. Drummer Rashied Ali opened Ali’s Alley on Greene Street, while saxophonist Sam Rivers and his wife Beatrice named their Bond Street loft Studio Rivbea. Ornette Coleman purchased a building on Prince Street which he called Artist House, and jazz singer Joe Lee Wilson opened the Ladies’ Fort, also on Bond Street. Other, less well-known players opened similar spaces: saxophonists David S. Ware and Alan Braufman, along with pianist Cooper-Moore, had a loft on Canal Street where David Murray may have made his New York debut.

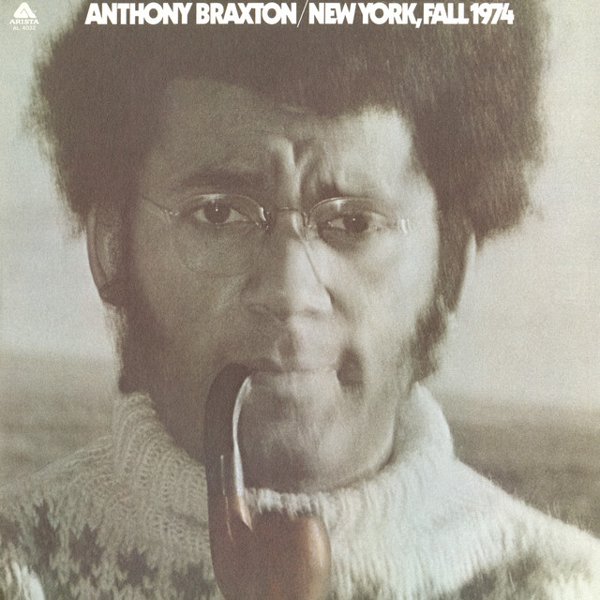

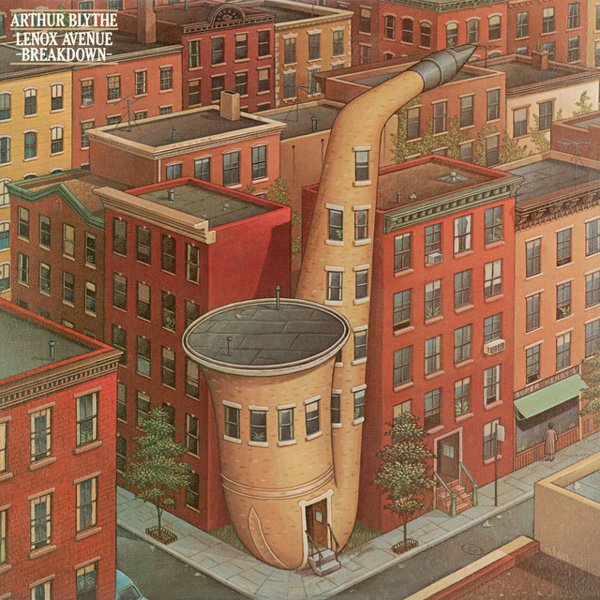

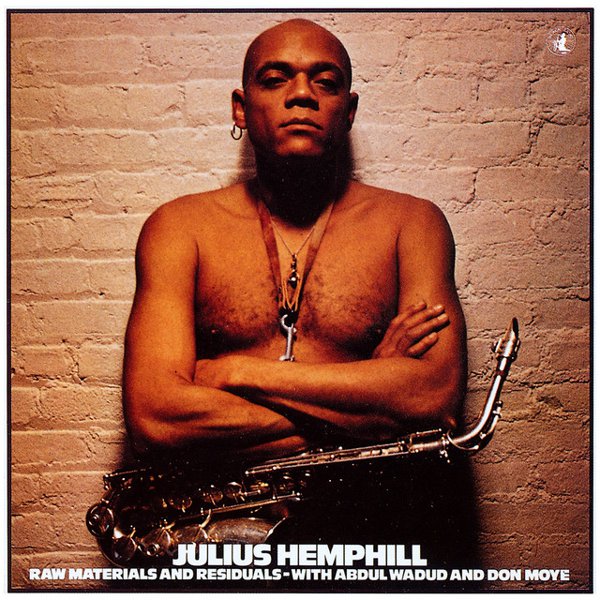

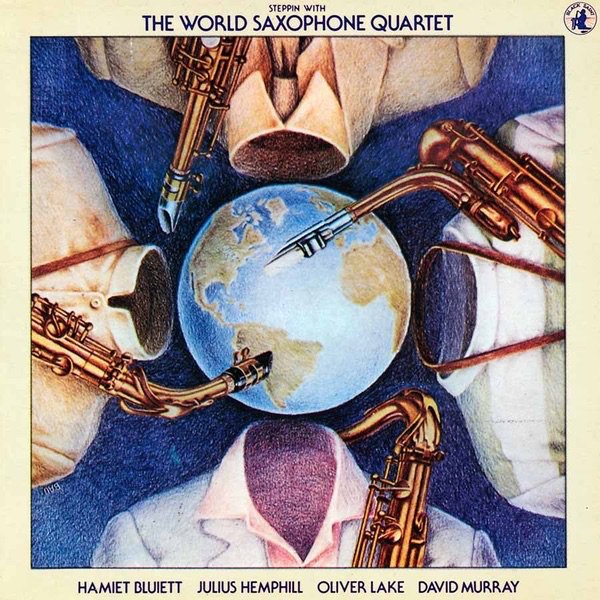

Murray, originally from Oakland, California, was just one of a whole school of new players to arrive in the early ’70s, bringing different ideas about the forms the music should take. Saxophonist and composer Anthony Braxton, pianist Muhal Richard Abrams, and several members of the Art Ensemble of Chicago migrated east, as did St. Louis’s Julius Hemphill, Oliver Lake, and Hamiet Bluiett. Alto saxophonist Arthur Blythe came from Los Angeles. Cecil Taylor, meanwhile, returned to New York in 1974 after teaching at the University of Wisconsin and Ohio’s Antioch College.

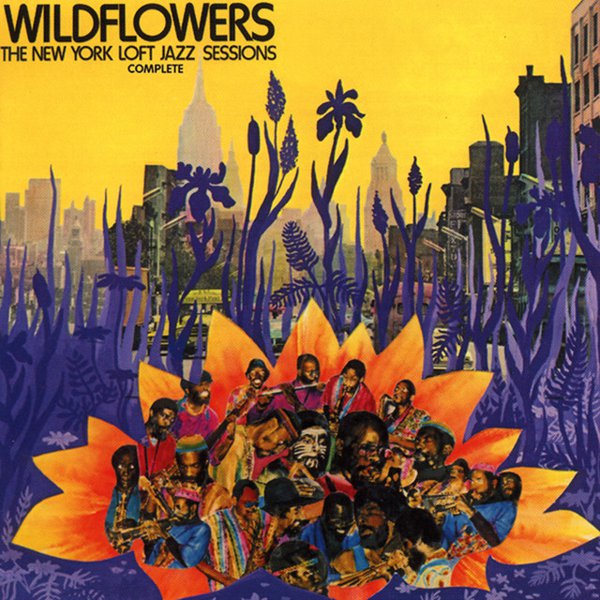

While expanding the music’s parameters through unorthodox instrumentation, extended solo recitals, blends of jazz and poetry, and other ideas, the artists on the loft scene also fostered self-determination and small-scale collectivism. Independent labels like India Navigation, Flying Dutchman, and Strata-East documented some of the music, and producer Alan Douglas talked the Casablanca label (yes, the home of Parliament, Donna Summer, the Village People and Kiss) into releasing five LPs’ worth of live recordings from Studio Rivbea as Wildflowers, but Hemphill, Smith, Taylor, and Ali released their own work on their own Mbari, Kabell, Unit Core, and Survival imprints.

Ultimately, the loft scene was an interregnum between the free jazz era and the more conservative jazz scene of the early 1980s. Gentrification and rising rents, which forced many musicians out of the spaces that had hosted so many performances and recordings, coincided with the arrival of the Marsalis brothers, Branford and Wynton, and the hard bop-oriented classicism of the so-called “young lions.” Still, the best music made in mid to late ’70s New York is as vibrant and creative as any in jazz history and planted seeds which flowered in the Downtown scene of the ’80s and ’90s, and the 21st century jazz avant-garde, which continues to exist and push the music forward to this day.