Psychedelia was cropping up in lots of different pop and rock in the late sixties, and acts as disparate as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, Funkadelic, Jefferson Airplane, Love and more were all experimenting with non-traditional song structures, fresh lyrical themes, experimental sounds and new studio effects. Inspired by the hippies and movements for social change like the emerging civil rights movement, psychedelia in music also owed a large debt to perception-altering drugs like LSD and cannabis.

One of the most successful early exponents of musical psychedelia in the late sixties was Sly and The Family Stone, who melded a hippie love and peace philosophy with soul, funk and acid rock. It was a potent blend that proved extremely popular and, via an introduction by The Temptations’ Otis Williams, one that was embraced and then developed by Motown songwriter/producer Norman Whitfield.

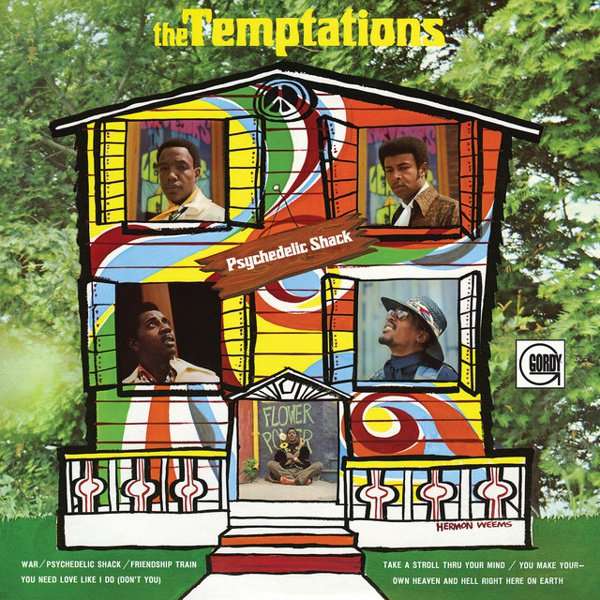

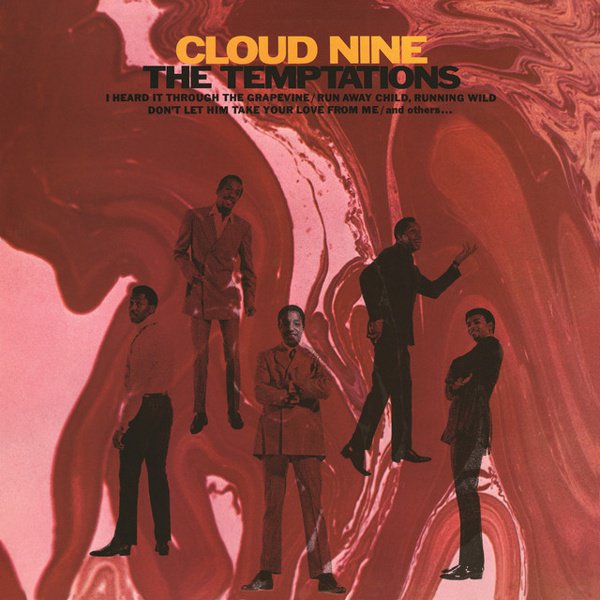

In 1968 (as told in Nelson George’s seminal Motown book Where Did Our Love Go), “…according to drummer Uriel Jones, Whitfield “came into the studio one day and said ‘I wanna do something different. I wanna do something fresh.’” The result was The Temptations’ Cloud Nine, the record which launched the psychedelic soul genre.

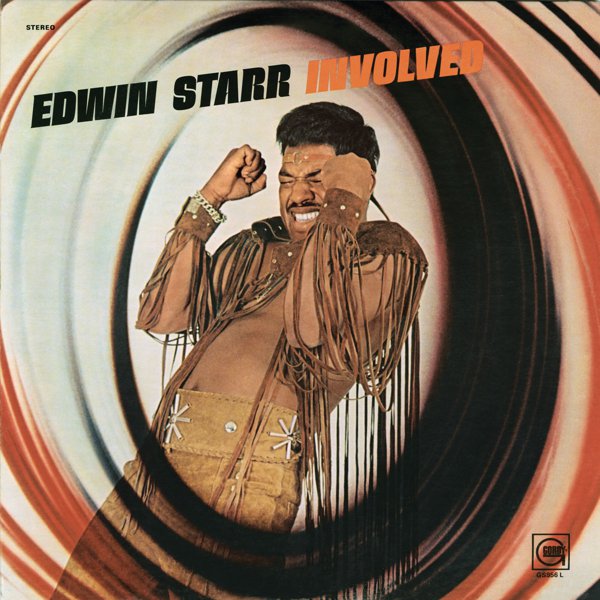

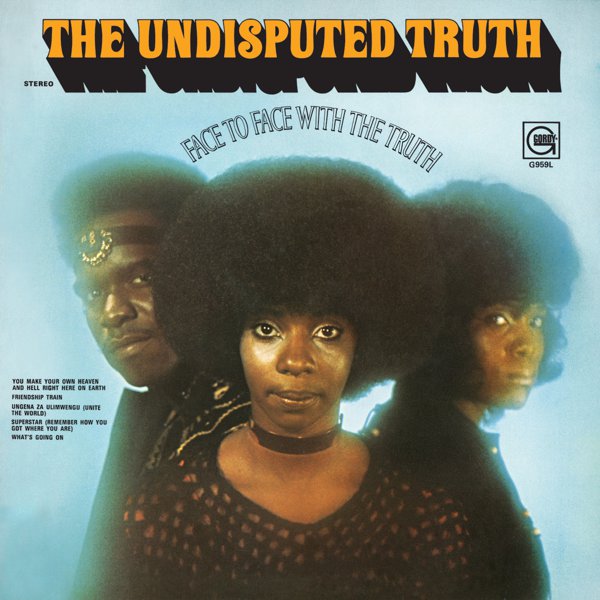

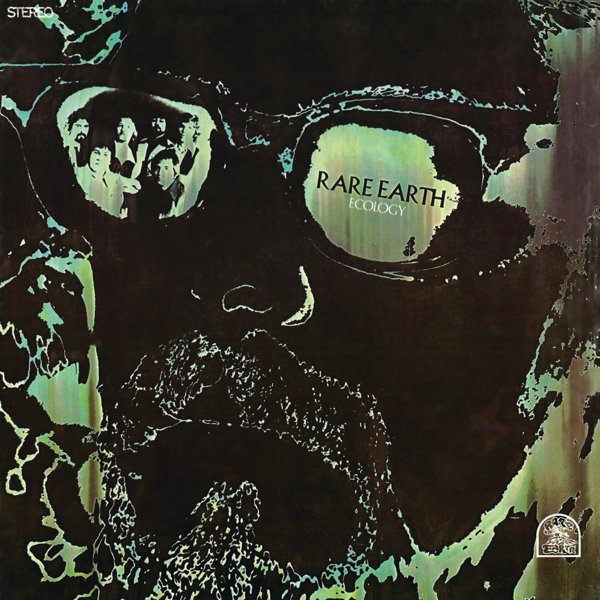

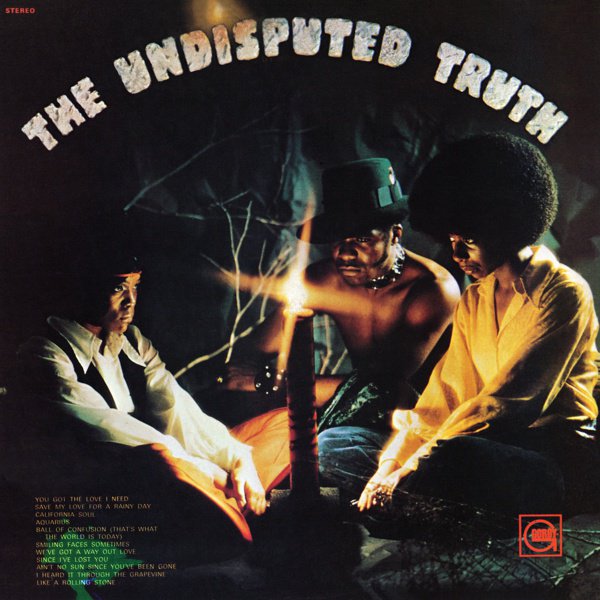

Throughout the late sixties/early seventies, Whitfield, in partnership with songwriter Barrett Strong, pioneered his vision of psychedelic soul with The Temptations, The Undisputed Truth, Edwin Starr and Rare Earth at Motown. It was an expansive, experimental sound which was characterised by topical lyrical themes that were often edgier and darker than Motown’s traditional love songs. Psychedelic soul introduced ‘trippy’ sound effects and production techniques to Black music, and its extended musical vamps and extensive percussion were also a precursor to the disco sound that would dominate the mid/late-seventies.

Cutting his music in Motown’s new, better equipped LA studio and using new musicians like funk guitarists Dennis Coffey and Melvin ‘Wah Wah Watson’ Ragin, Whitfield introduced a number of studio innovations. Cloud Nine was the first Motown record to use a wah wah guitar and Whitfield employed Cuban percussionist Mongo Santamaria to add the layers of fiery Latin percussion which would become a staple of the psychedelic soul sound.

To hear just what a dramatic change Cloud Nine was, you can compare it to the three 1968 Temptations singles that preceded it, ‘Please Return Your Love To Me’, ‘I Could Never Love Another (After Loving You)’ and big hit ‘I Wish It Would Rain.’ They were all a product of the classic Motown sixties production line, with lyrical themes of love, and straight-up pop/soul instrumentation sweetened with strings. Cloud Nine by contrast, with its harsh, realist lyrics, kinetic rhythmic rush, dark, brooding mood and futurist sound, arrived like a record from another planet.

Whitfield’s groups began to sing about subjects like racism, inequality and poverty rather than the love songs Motown had previously been famous for. Again influenced by Sly Stone, Whitfield also changed the way the Temptations sang, getting them to swap lead vocal lines back and forth and developing a much more percussive style of backing vocals.

Whitfield’s records also experimented with delay and reverb effects on vocals and acknowledged the emergent acid rock sound by extensive use of fuzz and distortion on guitars. He also began to elongate his productions, adding lengthy intros, instrumental vamps and breakdowns, stretching out his songs into huge, epic, looping grooves, pioneering many of the musical tropes that would come to define disco a few years later. In Where Did Our Love Go legendary Motown bassist James Jamerson observed that “Norman had never just wanted danceable grooves, but ‘monstrous funk’ that used two or three basic chords to define the different grooves on any particular record.”

The length of many of Whitfield’s productions opened the door to a new, progressive and experimental period for Motown, whose albums throughout the sixties had often been little more than a collection of hits and some filler. Whitfield’s records also influenced artists such as Curtis Mayfield, Isaac Hayes and Gamble and Huff at Philadelphia International Records, all of whom George says “…owed a debt to Cloud Nine for opening up black music and preparing the black audience for more progressive directions.”

Whitfield’s psychedelic soul productions simultaneously made the classic Motown soul sound an anachronism while completely revitalising the label. He, along with Motown house band The Funk Brothers, produced a body of revolutionary, edgy, funky, widescreen psychedelic soul music that proved to be extraordinarily influential and much of which sounds as fresh and exciting as it did when first released.