Scandinavian club-pop music has been something of a known quantity internationally since at least ABBA’s heyday, even if tastemakers from outside the region have often framed it as kind of kitschy and alien. And in a part of the world like Norway, where club culture’s connection to the idea of “nightlife” could range anywhere from six twilit hours in summer to 18 hours of darkness in the winter, it can be a tricky vibe to pin down — especially since anytime dance music spreads to the furthest-flung corners of the world it’s inevitably accompanied by a subgenre-splintering granularity that never keeps trends fully intact. In strictly commercial terms, the most successful dance acts out of Norway over the last decade or so — tropical house megastar Kygo, EDM hitmaker Alan Walker, prolific complextro synthesist Savant — could be considered the vanguard of the movement, and at least a couple of those names probably come to mind first for the average layperson with a passing knowledge of something that could be classified as Norwegian house music.

But something else ran through Norwegian dance-music currents starting around the turn of the millennium, not just in big cities Oslo and Bergen, but smaller municipalities where music provided an escape from semi-rural boredom. It was an idea that built off a few different impulses that had been percolating throughout dance music circles for a long time, identifiable in certain elements of French touch’s pop-disco reclamations or American indie-dance’s nu-no-wave or Kompakt’s microhouse minimalism. The Norwegians just synthesized something that was redolent of all these movements, and settled on calling their version of it “space disco.”

Space disco is, as forms of house go, fairly recognizable as a sort of link between the sun-kissed mid-tempo Balearic sound that endured from the ’80s through the ’00s, and the more crowdpleasing big-room song-driven tropical house wave that blew up in the mid-’10s. What makes it stand out is how deftly its practitioners sidestep the line between high art and low kitsch. Space disco is deliberately eclectic, largely because it reflects the lineage of the fans-turned-artists who came of age piecing together bits of other countries’ dance cultures in an attempt to figure out where they stood on their home turf. This generation of producers was primarily turned on to club culture and dance music through an adolescent fascination with hip-hop and electro. Like most nascent dance scenes, this one benefited from a nexus of independent radio and club DJs and their labels, like Vidar Hanssen’s Beatservice Records and a disco-revivalist wave championed by future Mungolian Jetset member Pål “Paul Strangefruit” Nyhus. These were people who learned as they went, but learned fast, picking up word-of-mouth highlights of a constellation of dance music scenes written about in UK and American press and developing a largely borderless eclecticism through a voracious yet discerning urge to hear something, anything new. Norway’s relative isolation from the musical hotbeds of England, continental Europe, and the USA didn’t prevent these DJs from finding a real connection to this music, but it did cultivate a breadth through restlessness.

Artists like Nyhus and Prins Thomas (who both hailed from the rural town of Hamar) and a group of scenesters originating out of the far-North small city of Tromsø (including Hanssen, Bjørn Torske, Ole Johan Mjøs, and Röyksopp) were able to maintain a tight-knit community of dance music heads who kept the faith as its popularity rose and receded during a revolutionary stretch of the post-rave ’90s. Oslo might’ve seemed like the ideal big-city culmination for space disco’s development, but the club scene there was a bit mercurial, frequently subject to overzealous policing, and contingent on an earlier-than-usual 3 a.m. curfew — Berlin it wasn’t — that left little room for slow-burning sets and demanded a dense highlight-reel momentum. And while the city’s clubland thrived in the late ’90s, it hit a massive snag by 2000 when two big epicenter venues, Jazzid and Skansen, closed down. But that obstacle just proved to be an important pivot point. The radio partnership of Strangefruit and Olle Abstract ultimately proved more influential than anything emerging from the masses spinning deep house at the nightlife spots. And a dearth of suitably daring club venues meant that developing DJs and producers had the tendency to stray from the genre-bound demands of populist sets and lean into a more personal and rangy, just-play-whatever idea of disco steeped in bedroom-studio networking — though they proved both popular and foundational to the next phase in Norway’s space disco movement when they were let out to do their own thing. (Strangely enough, this also meant that for what seemed like an idiosyncratic regional scene, most participants wound up becoming significantly more popular outside Norway than at home.)

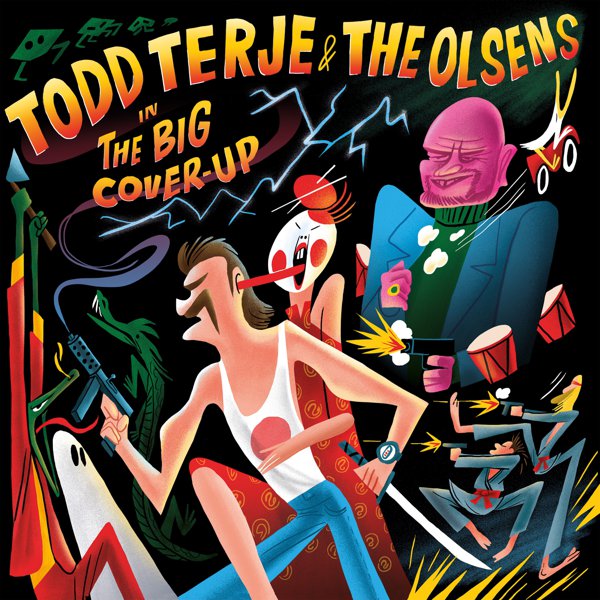

What they developed was a version of disco-house that was eclectic yet accessible, a sound that was less retro or even retrofuturistic than it was unconcerned with putting an actual timestamp on anything. It explored a symbiosis between avant-friendly art-dance and the unselfconscious anthemic drive of big club bangers, and the vibes this sound provided felt unpretentiously cool in a way that felt more welcoming than gatekeeping because it needed all the ears it could get. The intra-scene camaraderie and frequent brainstorming collaboration between a handful of artists proved to be more communal than insular, and the divergent yet compatible backgrounds of its leading practitioners meant that these sounds could retain their intrinsically funky-meets-artsy character without too much risk of it turning into a stagnant tunnel-vision aesthetic. A wave of small but strong artist-run labels ensued — Prins Thomas’s Full Pupp, Lindstrøm’s Feedelity, Todd Terje’s Olsen — though the polygenre indie label Smalltown Supersound proved just as crucial in spreading the work of artists like Torske and diskJokke.

And this stuff really endured. Some of the earliest gems of space disco date back to the turn of the 2000s, with the surprise success of Röyksopp’s debut Melody A.M. in 2001 proving something of a watershed catalyst. But it’s really just a continuation of the original spirit of disco as it existed in its pre-commercial Loft-era days, one that allowed for the kind of versatility that allowed room for proggy instrumental jams and pop-adjacent vocal tracks alike — not to mention the tendency for these guys to remix and edit anything they could get their hands on. (Terje’s litany of edits in particular are well worth tracking down, from excursions into classic disco deep cuts to stunning transformations of big-deal pop hits everyone knows, while the prolific remixer Thomas is equally unpredictable; in 2017 he even drew from his prog/psych enthusiasms to concoct a masterful reworking of Dungen’s Häxan.) Norwegian space disco’s big buzz moment might have come and gone, and in the scheme of things it seems a bit like a niche scene that vastly outperformed its potential. But it still feels vital just because its relatively small core of musicians have stuck with this malleable groove, one that continues to give them a lot of room to experiment and test and eventually expand what few flimsy borders might’ve originally delineated it.