A warning before we begin: this guide is far from comprehensive — it’s deliberately partial and full of major omissions. The thing is, it could only be that way. You could try and make a complete and definitive guide to the Balearic aesthetic in music, but the effort would inevitably destroy your mind and you’d probably have to go into hiding to boot. It is a contentious business to say the very least. Ask any five DJs what it means and you’ll get at a minimum six conflicting answers, and at least two of the DJs will hunker down into a bitter two week argument over whether Apollonia 6 or Wendy & Lisa are the most Balearic. There are even arguments over whether to capitalise the “B” of “Balearic” when referring to the music rather than the geography.

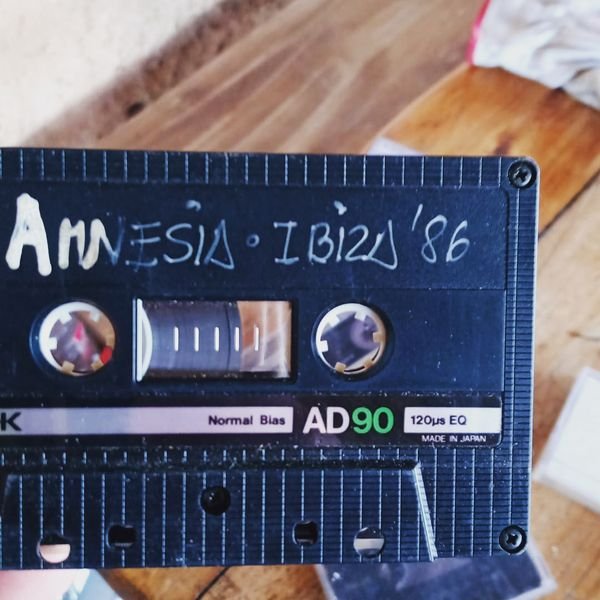

The canonical origin story is deceptively simple. Balearic music began in Ibiza – one of the Balearic islands off the eastern coast of Spain in the Mediterranean, and a longtime leisure spot for bohemians, hippies, queers, and other assorted beautiful people from around the world. The story goes that it began with the musical choices of Argentinian DJ Alfredo Fiorito (universally known just as Alfredo), who began a residency at the Amnesia club in 1984 just as the club got an all-night license, and just as the followers of the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh aka Osho brought suitcases full of ecstasy to the island as they fled their cult compound in Ohio. This then got taken to the world by a bunch of cheeky chappies from London.

Alfredo played all sorts. There was plenty of the pop and soul of the time. Lots of new wave / alternative like Talking Heads, Billy Idol and Siouxie And The Banshees. Euro electronica that bordered on the industrial like Belgium’s Liaisons Dangereuses or Scotland’s Finitribe. 60s and 70s psychedelic rock. Latin grooves. Reggae. Nina Simone. Captain Sensible. The Pink Panther theme. Quite a lot of the cheesiest smooth jazz sax you’ve ever heard. House music as it began to filter in from Chicago and New York. All at a distinctly unhurried pace. In the summer of 1987 a bunch of young London clubbers came to Amnesia, had their ecstasy epiphany dancing to U2 and Mr Fingers at dawn, took the experience back to the UK as evangelists via clubs like Paul Oakenfold’s Future and Danny Rampling’s Shoom, and together with acid house it exploded outwards.

In fact though, it’s a bit more complicated than that. There’s an element of “history is written by the victors” to this narrative – that is to say, those Brits went on to hugely influential positions in the music industry, so the places and sounds that first turned their heads were written into the canonical definition. But when Alfredo started, he played a very simple mix of laid-back pop-soul – mainly a huge amount of Sade – without the variety he’d be known for a couple of years later, and there were plenty of other DJs at clubs like KU and Pacha and bars and parties across the Balearics mixing it up, with influence criss-crossing between them.

These included Alfredo’s own stated biggest inspiration, Frenchman Jean Claude Maury, who had cut his teeth in the 70s discos of Brussels and had brought a lot of the weird Belgian electropop influence with him. Italian KU resident Massimo “Max” Zuchelli was much revered by other DJs. Names like Pippi, Joan Ribas, Gerardo, Patrick Landry, Nelo and Juan Carlos were all mixing, matching and cross-fertilising through the early- to mid- 80s. And one of the key Brit popularisers, Trevor Fung, had been playing Ibiza since almost the start of the decade – while other music lovers and mischief makers came and went, taking Balearic fashion and tastes back to British and other European cities. So as much as the events of 87 and 88 were a tectonic shift, the Balearic aesthetic had already grown in conversation with the rest of the continent long before the mythical 1987 year zero.

Listen now to mid-80s DJ recordings, and you’ll see why the crowd of jetsetters, pop stars, hippies, urchins, drop-outs and weirdos from across Europe revered Alfredo and the other DJs. There was no technical trickery to the mixing, but their pacing and choices draw you in – one minute it’ll be just Simply Red and Sade and you’re wondering how it’s different from oldies radio, then you’ll realise you’re nodding your head to something completely alien, or which shouldn’t make sense yet does. The old cliché of a DJ taking the audience “on a journey” is made vividly real, but it’s not hypnotic electronics or slamming basslines, it’s Spandau Ballet and TV cop show themes getting you there. It doesn’t matter if a track was a million-seller or a mega-rarity, if it fits, then it fits.

Right away the disagreements start. Does a song become Balearic because Alfredo played it, or is there a distinct quality that made it Balearic all along? All those other clubs and cafes through Ibiza, Formentera, Menorca and the other Balearic islands started playing diverse connoisseurs’ selections too: are they also officially Balearic music? What are the qualities that link these songs? Certainly there’s a certain inclination towards high production values, clean lines, a bittersweet melancholy that speaks to the fleeting bliss of the ecstasy experience. But a sense of fun is just as present, and the smoothness can be interrupted at any time with a psyche rock wigout or some rough-edged Euro EBM.

And the complications multiply once you factor in what people took away from the Amnesia, KU and Pacha dancefloors. Even in the mid-80s, artists were aware of the sound of those clubs, and either deliberately tailored their work to be playable or simply took inspiration from the Balearic DJs. From the ostentatious lushness of soft rocker Chris Rea to New Order fully leaning into their electronic tendencies while recording and clubbing in Ibiza, the Balearic vibe radiated outwards, creating feedback loops together with mainstream and alternative music. Other club scenes from Belgian new beat to Italian cosmic disco likewise existed in a state of sympathetic vibration with the Balearic isles.

But that was as nothing to what happened after 1988 and in the first couple of years of the 90s. That year, ecstasy culture exploded out of Ibiza across the clubs of Europe and particularly the UK. Already a few oddballs within the football terrace and club cultures had adopted the hippie-ish Amnesia style, but with the acid house revolution, it was suddenly everywhere, with DJs hunting down Alfredo’s playlists obsessively. And the Ibizan sound blurred into many other things. UK street soul birthed the likes of Soul II Soul and Smith & Mighty, whose unique loping breakbeat style and soundsystem bass would feed heavily back into Ibiza. Indie bands went to Ibiza or hung out with DJs who had. The likes of Happy Mondays, Primal Scream and the Beloved created a whole Balearically-inclined indie-dance movement. Acts that were neither indie nor dance, like Saint Etienne, Moodswings, The Grid, Innocence and many more, produced downtempo and emotive anthems.

Meanwhile in 1991, something happened that confused definitions even more: already well-practiced DJ Jose Padilla began his residency at Ibiza’s Cafe Del Mar, playing as the sun set over the ocean. His sets, though they could include dance and soul-funk beats and were as varied as Alfredo’s, were fundamentally more chilled. Playing soundtracks by Ennio Morricone and Ryuichi Sakamoto, new age and minimalist tracks by the likes of Penguin Cafe Orchestra, and selling tapes of his sets, he created an association between Ibiza and chillout music that changed the meaning of “Balearic” even as it was settling into the wider public consciousness. And to mess things up more, that public consciousness would also start to think of the banging trance and prog house of mid- to late-90s megaclubs as Balearic as well.

Since then, layer upon layer of variation have been added. DJs around the world from Copenhagen to Kyoto made careers from a laid back yet ecstatic vibe. Some, epitomised by Andrew Weatherall, led with the darker, more industrial side of Alfredo’s tastes, merging into more techno flavours. Some found overlaps with other stylistically voracious hedonistic scenes - like the cosmic disco of 1980s Italy led by Daniele Baldeli, or the Loft parties started in New York by David Mancuso going way back to the start of the 70s. Indeed, Colleen “Cosmo” Murphy, an associate of Mancuso’s, has lately presented a Balearic Breakfast Show on Worldwide FM, shoring up the sense of kinship between similar open-minded ecstatic dancing scenes.

Whole labels have grown up from releasing new dreamy dance experiments with a Balearic flavour (one is even called “Is It Balearic?”), or from digging up and re-releasing the type of obscure records that Alfredo might have played. Local variants have sprung up like the Norwegian disco scene of the 00s which tapped into cosmic disco, Ibizan influences and a whole load of bongos to create some of the most genial music of the new millennium. But is it Balearic? Well, here come the months-long arguments. Some say it’s not Balearic unless it’s actually a fish shack on an island beach with a wizened old hippie or hooligan playing Cocteau Twins and Jimmy Cliff singles. Some think it needs to be connected to certain clubs in London or Manchester. Some think there’s an aesthetic with rules, others demand that there must be rule-breaking curveballs to count.

But the brilliance of the legacy of those original, endless 1980s Ibiza nights is that nobody ultimately can decide what is real or authentic any more. So much of the magic is tied up with contingent experiences, the time of night, the juxtaposition of tracks, the cultural mix and expectation of a crowd at any given moment, the colour of the sunset, the flux of innocence and experience…in that sense it’s the epitome of club/DJ culture’s unique constitution: a record itself, or even a DJ set, can never be the definitive artwork, because the artwork – the creativity, the expression – is made up of the night, the weekend, the summer, the life story. This is a musical experience that shifts, shimmers and changes with every experience across decades and nations.

So with that in mind, I’ve selected some good records that have had the B-word attached to them at one time or another – many of them are explicitly Balearic compilations, in fact – but I ascribe no great claim to definitive status for any of them. Rather, think of this as a way in, a hint of how to navigate your own tastes, a waft of pine and patchouli as you try and track down that great mythical Mediterranean party of the mind…

![Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5116979142197248_600.jpg)