Bluegrass music is an American country subgenre generally known for conforming to a fairly specific formula: the typical band consists of guitar, mandolin, banjo, fiddle, and bass, with the guitarist singing lead and the mandolinist singing tenor harmonies. While traditional bluegrass bands have varied from this formula somewhat over the decades, the formula has nevertheless persisted. The musical content of bluegrass, however, has steadily expanded over the years, from an early focus on traditional fiddle tunes and ancient (or ancient-sounding) songs to adaptations of pop songs, increasingly jazzy instrumental compositions, and fusions of various other genres with bluegrass inflections and instrumentation.

What would come to be called “progressive” bluegrass has some of its earliest expressions in the late 1950s, when the Washington, DC-based Country Gentlemen formed and almost immediately began adapting non-bluegrass material such as “A Good Woman’s Love” by Cy Coben and the wind band composition “Under the Double Eagle.” They would eventually add to their repertoire songs by Graham Nash, the Beatles, John Denver, and others, while maintaining a more or less traditional bluegrass instrumentation and playing/singing style.

The Gentlemen paved the way for more adventurous experiments. In 1971, several forward-looking young musicians including mandolinist Sam Bush and banjo player Courtney Johnson (both of whom broke off from the Bluegrass Alliance) formed a band called the New Grass Revival. Sporting long hair and hippieish clothing, this group went even further afield in its style and repertoire, adapting rockabilly and reggae songs to the bluegrass format – much to the consternation of some more tradition-minded fans. Elsewhere, the Seldom Scene was organized by several former members of the Country Gentlemen and continued that group’s tradition of expanding the stylistic boundaries of the genre, including playing long and exploratory solos in its live concerts that could at times (in their length and discursiveness, at least) evoke the psychedelic excursions of the Grateful Dead. During the 1970s women began taking a more prominent role in what had historically been an almost entirely male scene, as Kathy Kallick and Laurie Lewis formed an all-woman band called the Good Ol’ Persons and eventually went on to illustrious and stylistically expansive solo careers.

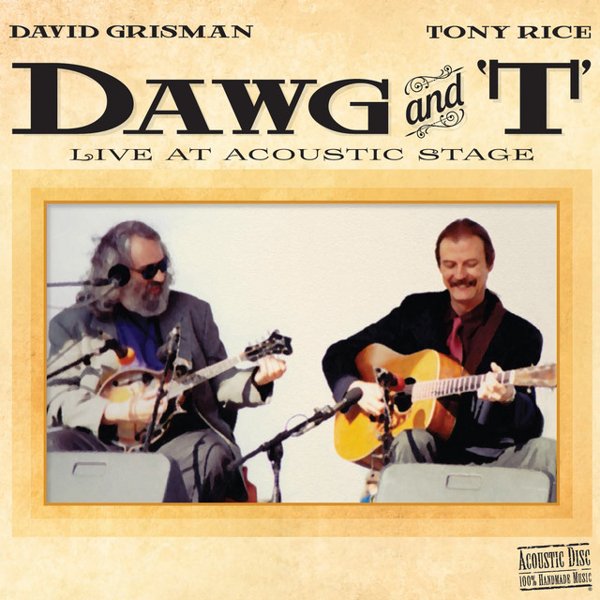

In the later 1970s came the emergence of what would come to be called the New Acoustic Music movement. This phenomenon was largely a product of the California bluegrass scene, where a core of musicians centered around mandolinist David Grisman, guitarist Tony Rice, and mandolinists/fiddlers Mike Marshall and Darol Anger were experimenting with a fusion that blended elements of hot and Gypsy jazz with bluegrass conventions and instrumentation to create an entirely new genre of acoustic music.

In recent years all remaining walls around bluegrass convention seem to have fallen, with sometimes thrilling results. Bands like Nickel Creek, the Punch Brothers, the Infamous Stringdusters, and Mumford & Sons (as well as solo artists like Sarah Jarosz and Billy Strings) have created new and at times highly personal pop and roots subgenres that draw significantly on the history and traditions of bluegrass, while pledging no stylistic allegiance to those traditions. At the same time, highly traditional bluegrass artists have continued to enjoy success, suggesting that despite the apparent stylistic tension between them, these multiplying streams of musical style will continue to coexist fruitfully for many years to come.