Art school. 60s rock and soul. Classic Hollywood films. Outrageous costumes leading to suave 30s styles. All this, plus an English post-war society theoretically committed, at least temporarily, to the idea that you could make the most of yourself by doing whatever the heck you wanted to as opposed to what society expected of you. Roxy Music arguably could have emerged only exactly when it did in the early 1970s, in a swirling ferment collectively termed glam rock that covered everything from Marc Bolan’s whimsical grooves to Slade’s shout-along stomps. Formed in London but with roots across the map, from guitarist Phil Manzanera’s upbringing throughout the Americas following his English dad’s work commitments and his Colombian mother’s musical leads to lead figure/keyboardist Bryan Ferry’s working class youth in northeast England and early synth player Brian Eno’s small town life in Suffolk, Roxy Music remains a shorthand for both chaotic experimentation and serene elegance in guise of a rock band. As of 2023, having completed a 50th anniversary celebration tour with Ferry and Manzanera joined by other core members sax/woodwind player Andy Mackay and drummer Paul Thompson, the band still exists as a well-loved touchstone, while Eno and Ferry in particular as well as Manzanera and Mackay have carved out lengthy solo careers both as central figures and as collaborators and producers.

Thompson built himself up from scratch, becoming a working drummer while still a teenager and eventually leaving behind a metalworking career to pursue those opportunities further. Meanwhile, all the other key members of the group had student backgrounds that shaped their approaches. Ferry studied fine art in Newcastle, at one point notably having pop art figure Richard Hamilton as an instructor. Eno was similarly involved in fine arts at Winchester, receiving much encouragement from visual artist Tom Phillips, while Mackay studied music and English literature at Reading. Besides the educational pursuits that fed into their future work, all three worked in a variety of bands during those years, while Manzanera worked in student bands at Dulwich College in London.

It was Ferry, who had worked in a student band at Newcastle with bassist Graham Simpson, who got the ball rolling in London in 1970, and following Ferry’s unsuccessful singing audition for King Crimson, that band’s leader Robert Fripp later recommended the formative group to his own label, EG Records. Over the next couple of years the band’s lineup evolved as various players were added or dropped, with Mackay joining first and then suggesting Eno, initially as a technical expert and then adding in a unique chaos factor with early synthesizers. Thompson followed via auditions later, with Manzanera joining first as a roadie to support a separate audition winner, the Nice veteran David O’List. When O’List abruptly quit in early 1972, Manzanera easily slotted in following his own informal audition.

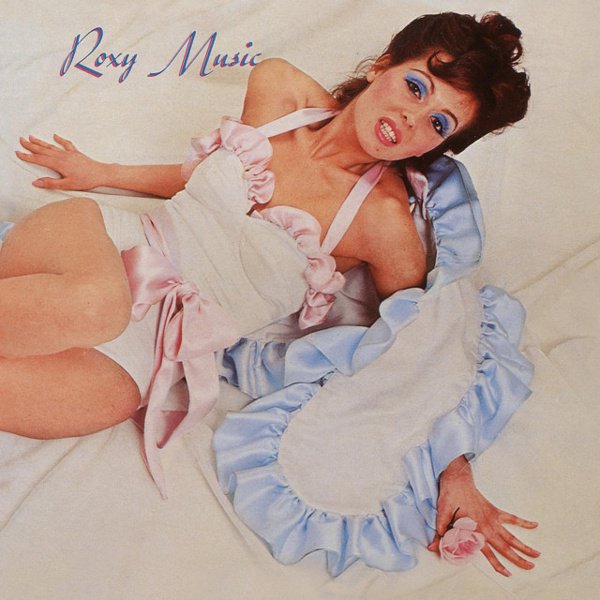

The band made its initial splash via its remarkable self-titled debut album, a kaleidoscopic and simultaneously bizarre and immediately memorable melange of pop styles that played out visually as much as musically, with Eno’s work in particular providing an experimental edge underpinning Ferry’s dramatic vocal approaches. In a sign of what would be permanent instability, Simpson departed soon thereafter, leading to a rotating series of bassists ever since, while the standalone single “Virginia Plain” became a top 5 hit, bringing the group a wider audience and leading to a regular appearances on the UK charts and then beyond.

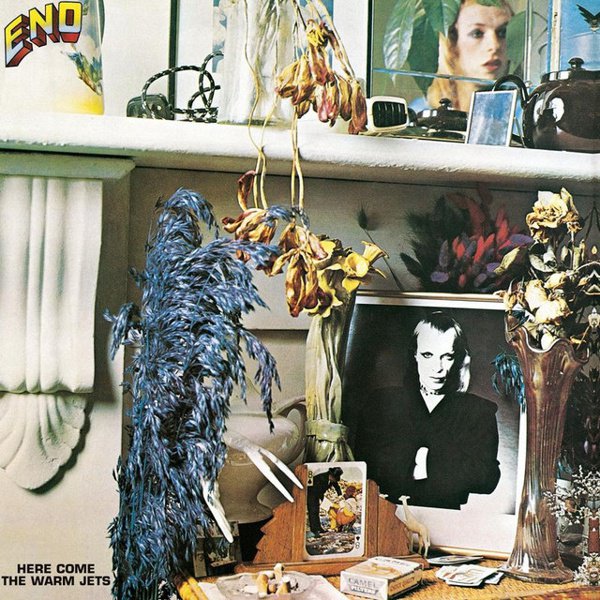

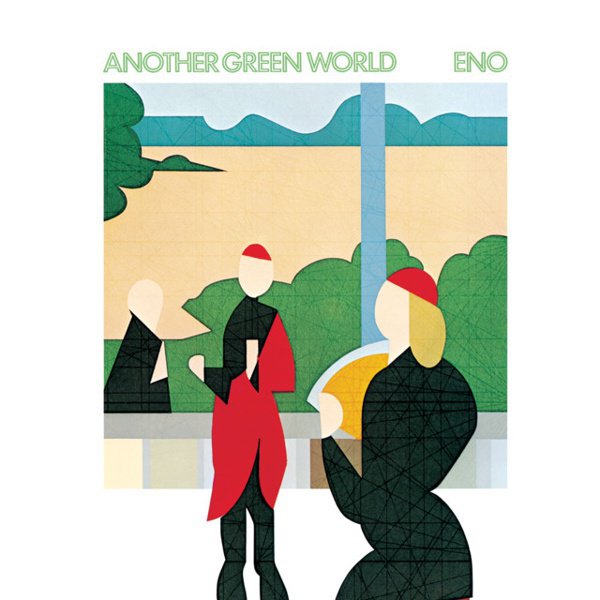

That said, a certain chronic instability at the heart of the band only increased in 1973. On the one hand, following the release of For Your Pleasure and its subsequent tour, Eno found his own artistic goals increasingly at odds with Ferry’s and left the group, initially releasing the first of various collaboration albums with Fripp, (No Pussyfooting), and then beginning a full solo career the following year, often working with Fripp and continuing to work with a variety of Roxy Music musicians as well – Ferry notably excepted. However, Ferry himself began his own solo career in 1973, though in slightly indirect fashion, with his debut These Foolish Things consisting solely of often heavily rearranged and rethought cover versions from a variety of artists stretching back to the Great American Songbook, all also while working with a variety of his Roxy bandmates in turn.

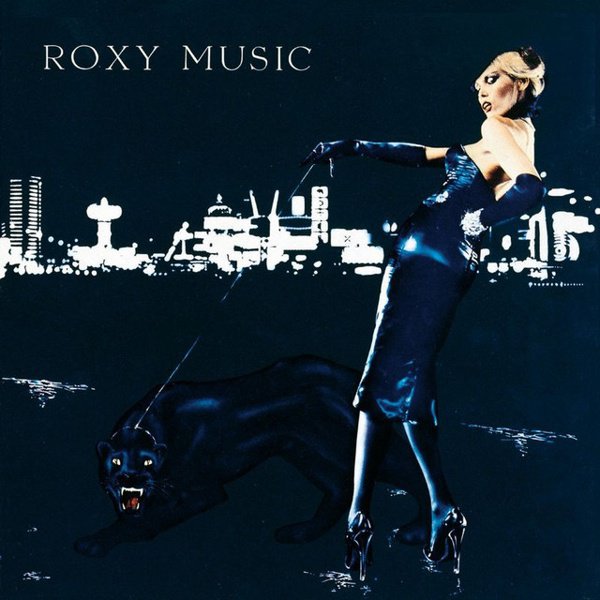

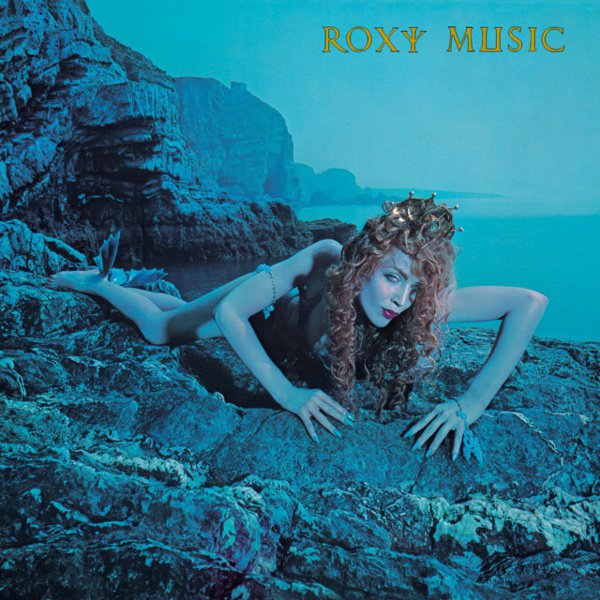

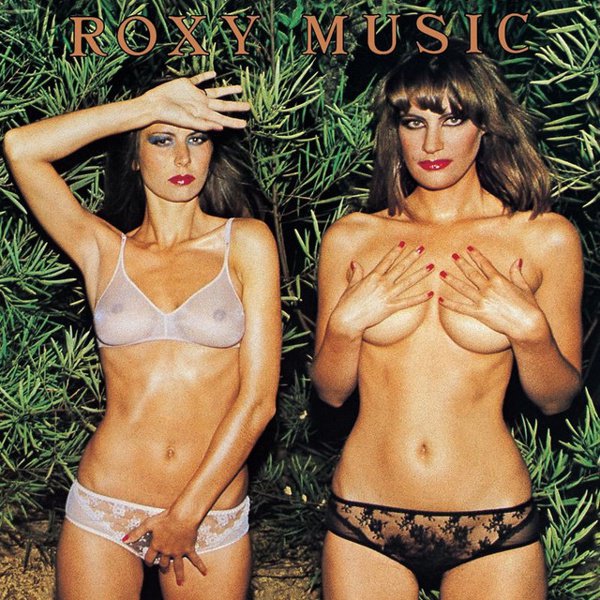

The next few years showed Roxy Music itself moving from strength to strength, with Eno’s replacement, violinist Eddie Jobson, bringing his own creative skills to create new arrangement approaches, with the Country Life album being a particular creative high point; while the subsequent album Siren wasn’t quite as strong, it did also led to an American breakthrough thanks to the crisp, suave funk of the hit single “Love Is The Drug.” Following a tour for that album, however, while Roxy went on hiatus, nearly everybody kept going on a variety of fronts, often interrelated.

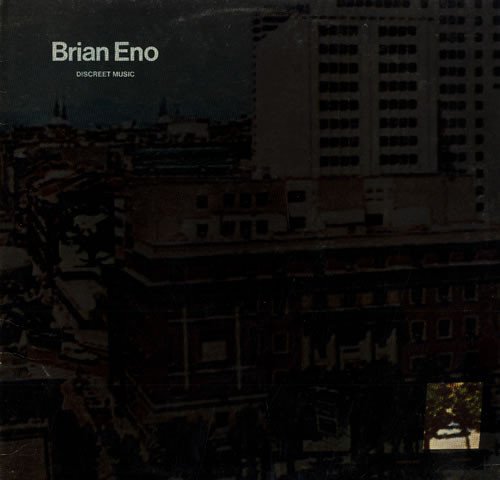

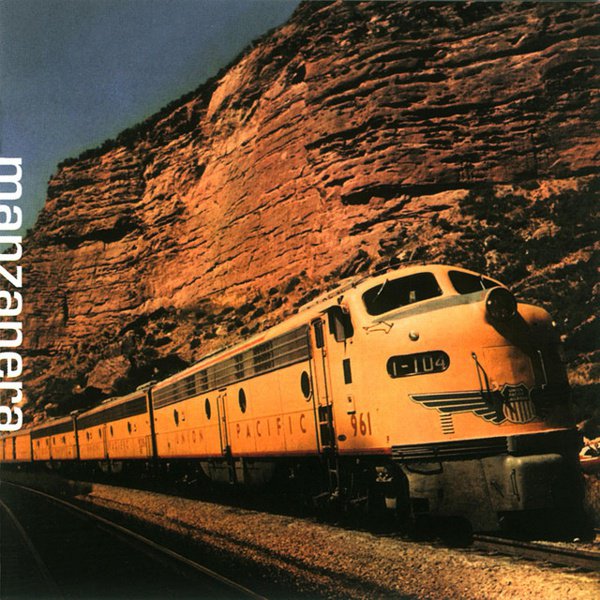

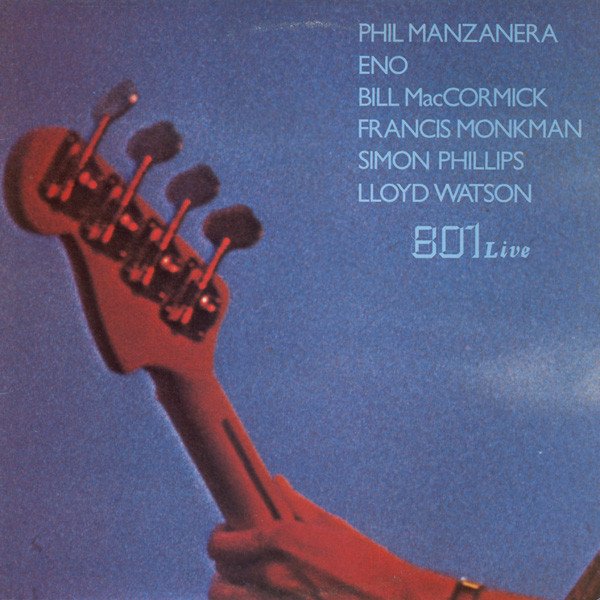

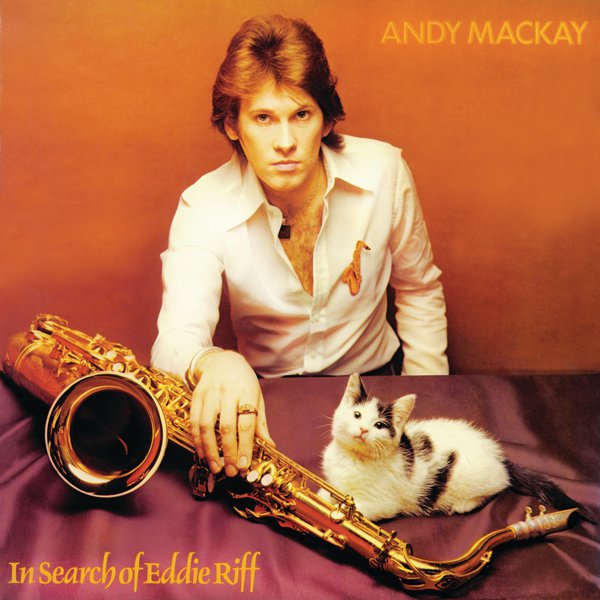

Accompanied by various Roxy compatriots like Manzanera, Thompson and Jobson, Mackay had released an initial instrumental solo debut in 1974, In Search of Eddie Riff, though it was the later soundtrack to the UK TV show Rock Follies, about a struggling vocal trio, that gave him a 1977 number one hit album in that country in collaboration with lyricist and series screenwriter Howard Schuman. Manzanera had pulled off a bit of a double side project debut in 1975 with both his own Roxy-performer-heavy solo debut Diamond Head and a self-titled album by Quiet Sun, reuniting members from a pre-Roxy band of his to record their old material. A subsequent project including Manzanera and one of his Quiet Sun bandmates Bill MacCormick, 801, made its debut via a live album drawing from 1976 concerts; another 801 member, who had also taken lead vocals on two of Diamond Head’s tracks, was Eno. The latter’s own solo career was not only thriving but was soon to lead into the first of many famed efforts as a producer for and collaborator with others such as David Bowie and Talking Heads; even more crucially, he’d begun to explore what he would soon be famed for: extensive, understated instrumental pieces he termed ‘ambient’ music, essentially founding a genre tag as a result.

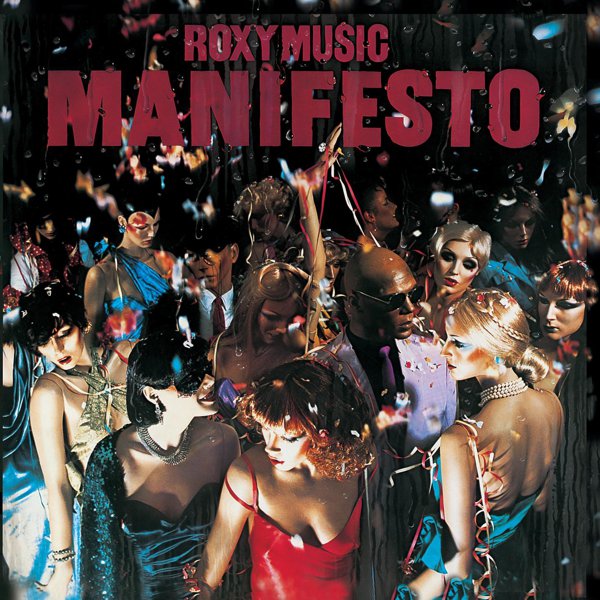

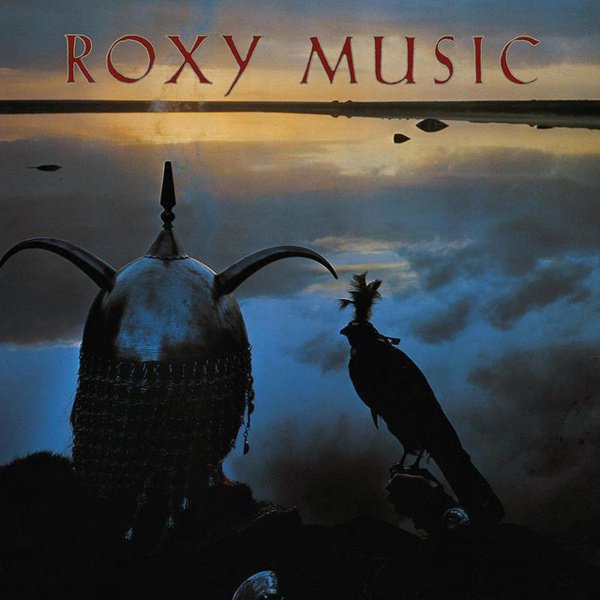

Ferry, meanwhile, continued his own solo career both before and after the Roxy hiatus, continuing to cover various songs by others but shifting more towards original efforts. In 1978, he reactivated Roxy, rejoined by Manzanera, Mackay and Thompson as well as other new players. Thompson, however, would only briefly appear on the recordings for 1979’s Manifesto, working elsewhere during what proved to be the last run of Roxy studio albums, including 1980’s Flesh + Blood and 1982’s Avalon. The latter became a landmark of mood music for that decade and beyond, with the chaotic leanings of a decade prior now turned into heavily shaped but beautifully compelling songs for late evenings at nightclubs and lovenests. Along with a valedictory salute to the slain John Lennon via a cover of “Jealous Guy” that reached number one in the UK, that ended Roxy as a formal recording unit.

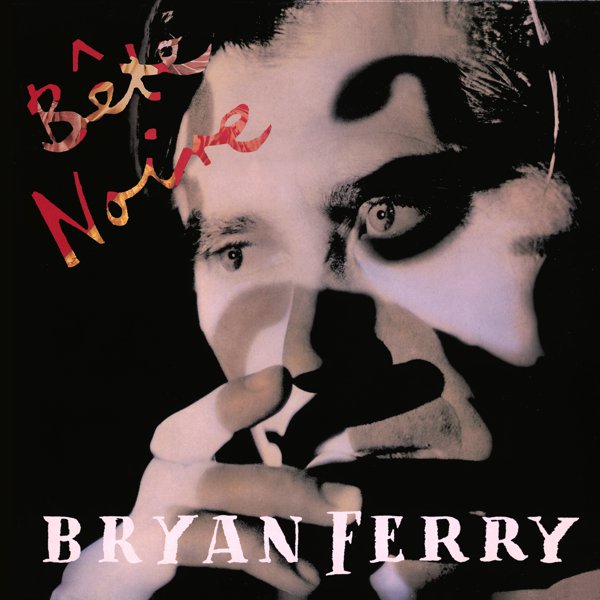

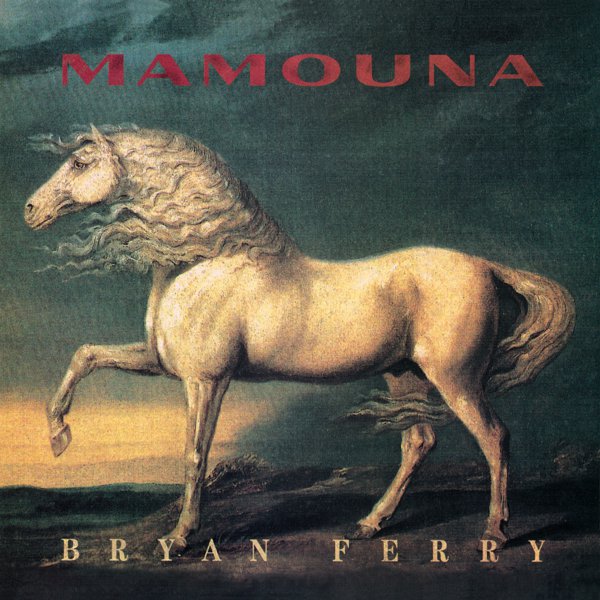

Ferry worked off and on with many veterans from Roxy’s later incarnations in his revived solo career beginning with 1984’s Boys and Girls, essentially taking up where Avalon left off. Manzanera and Mackay’s own solo careers continued over the decades, both individually as well as a Roxy-ish collaboration in the 1980s as the Explorers as well as any number of collaborative and session player credits, particularly on Manzanera’s part; Thompson in turn has played with Mackay as well as a variety of other bands and efforts over the years, including Concrete Blonde and Lindisfarne. Eno, meantime, became a superstar producer in his own right, most famously thanks to his work with U2 in particular, while continuing to record both ambient and instrumental efforts as well as occasional vocal turns, particularly in more recent years.

While Eno firmly sat out the irregular Roxy live reunions that began in 2001, he’s still contributed efforts to Ferry’s solo releases here and there over time, as have Manzanera, Mackay and Thompson. Roxy Music is very much a legacy now, but whether the obvious stylistic descendants like Chic and particularly Duran Duran or the more shaggily inclined or unexpected disciples like noted Ferry fanatic Robyn Hitchcock or the Welsh sonic wizards Super Furry Animals – and those all are just the 20th century examples – it’s a legacy that’s still reverberating.