The soul music that emerged from the Southern states of the USA, especially Memphis, Tennessee and Muscle Shoals, Alabama, has a particular flavour and style — raw, direct, honest, expressive — that is distinct from the accessible, refined, cross-over pop-soul of Motown, or the slick, orchestrated ‘soft’ soul of Chicago.

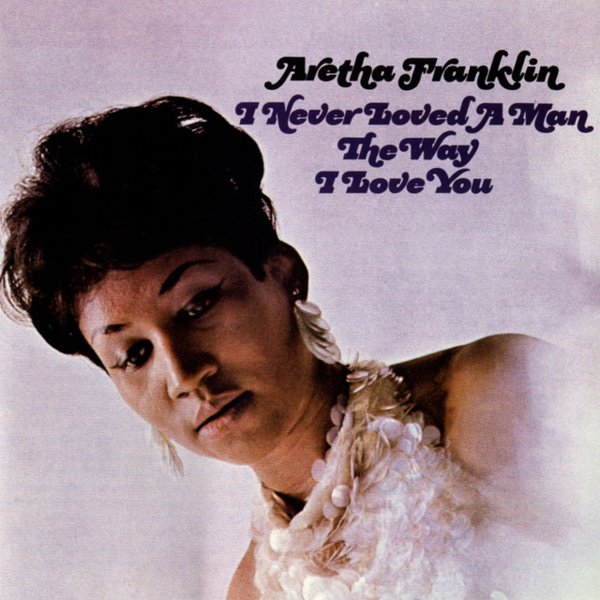

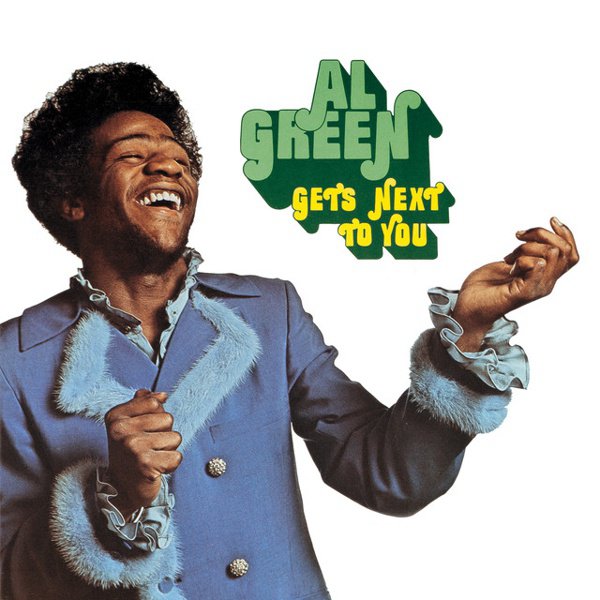

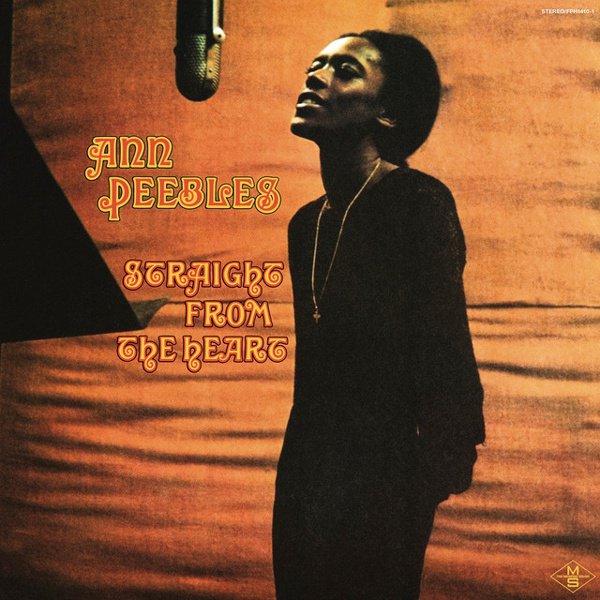

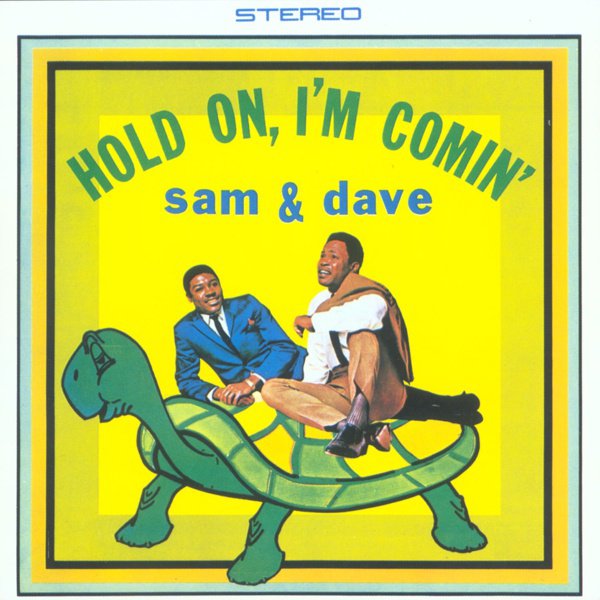

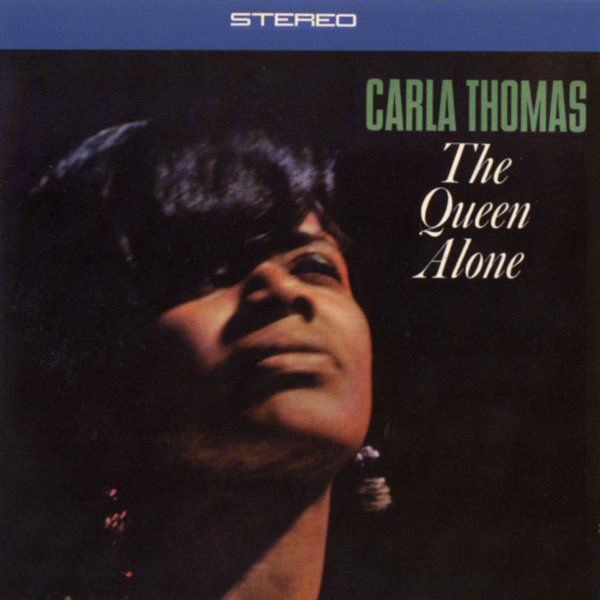

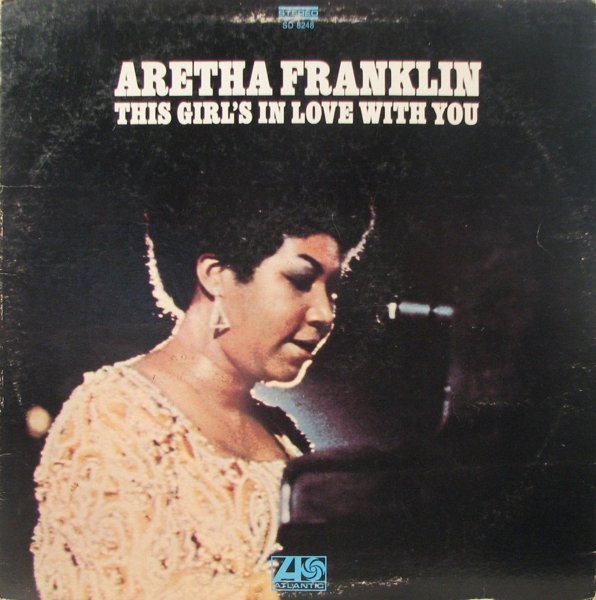

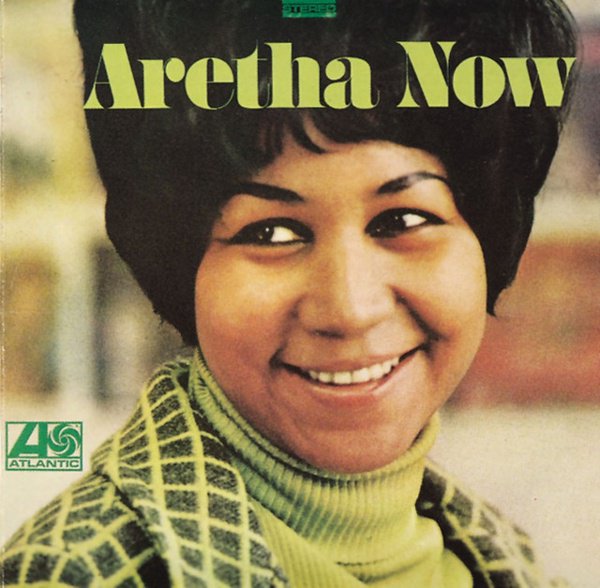

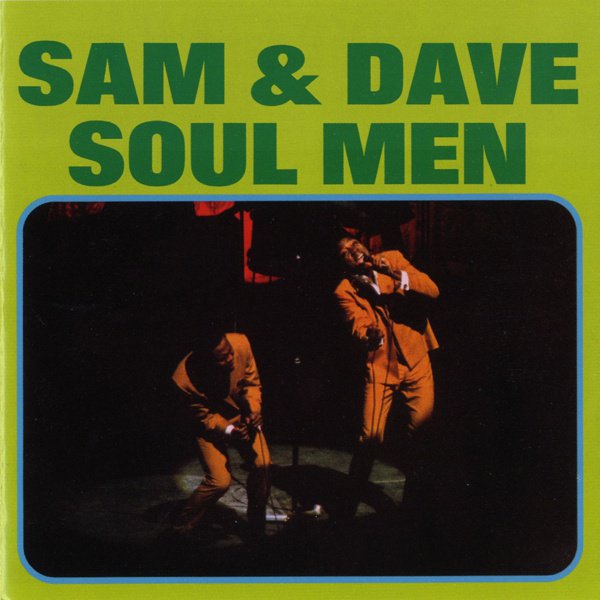

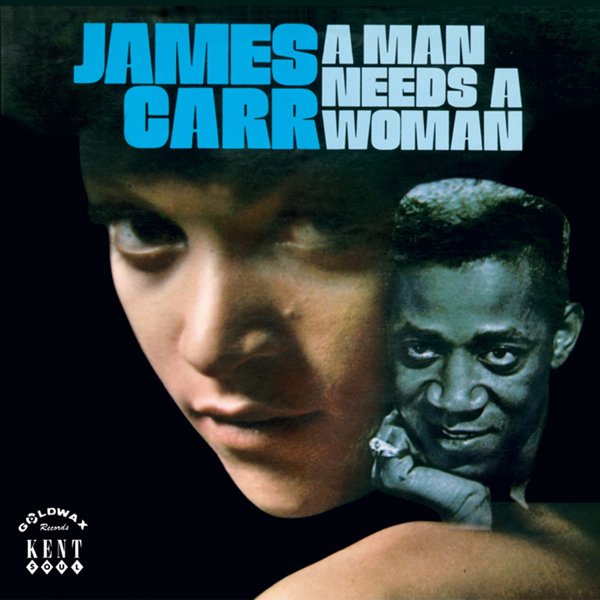

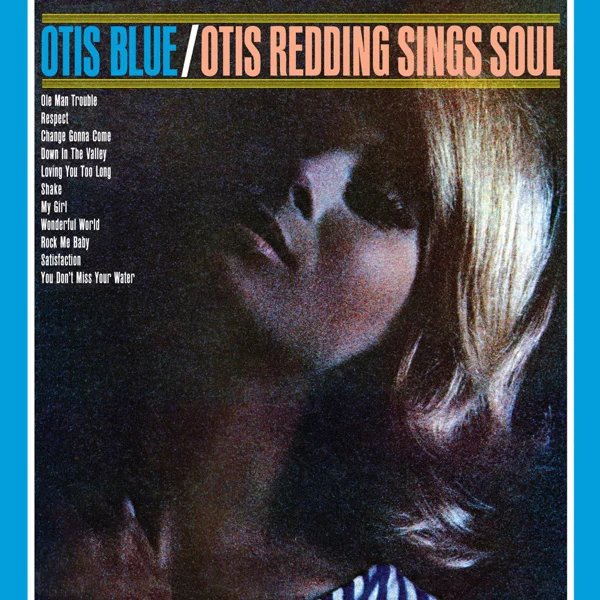

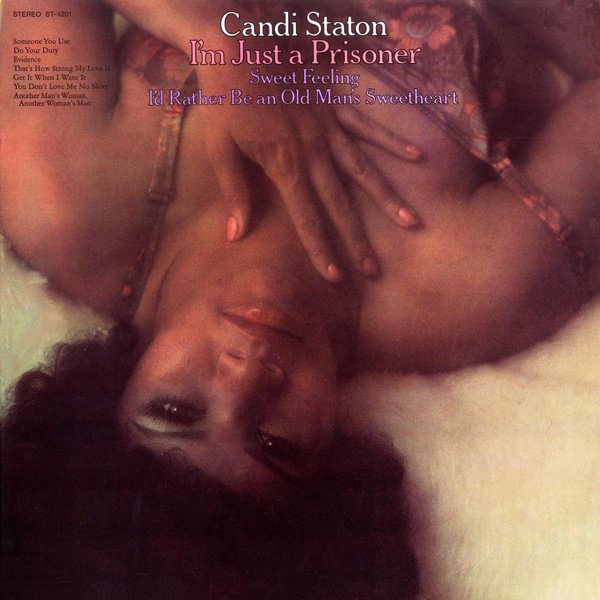

Memphis was home to Goldwax Records where deep soul legends like James Carr and O.V. Wright recorded, as well as Hi Records where Willie Mitchell produced artists like Ann Peebles and Al Green. The biggest Southern soul label Stax, also based in Memphis, released music from Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Carla Thomas, Sam & Dave and more. Stax house band Booker T & the MGs and horn ensemble the Memphis Horns were central in shaping the character of Southern soul, along with the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section from FAME (Florence Alabama Music Enterprises) Studios, who also played on many Stax hits and recorded with artists like Redding, Pickett, Solomon Burke, Joe Tex and Eddie Floyd. The Muscle Shoals band also played on Aretha Franklin’s string of seminal sixties soul albums, as well as music from pop/rock artists like The Rolling Stones, Paul Simon and Joe Cocker.

Southern soul is generally thought of as rawer, more authentic and more immediate than its Northern counterpart, and no doubt the sixties output of labels like Stax or Goldwax were generally more hard-driving, gritty and unembellished than that of Chicago’s Curtom or Motown in Detroit. But that’s not to say Southern soul is less sophisticated. It’s direct, honest music, but Southern soul isn’t just about a down-home country feel — in his epic history of Southern soul, Sweet Soul Music, writer Peter Guralnick notes that the genre arose in a particular time and set of circumstances, the end product of “the bitter fruit of segregation transformed into a statement of warmth and affirmation,” a description you’ll find hard to beat.

It developed in relative isolation, at least in terms of being far from the major urban centres of the music business and was in many ways a cottage industry, peopled with freelancers. Southern soul was also influenced by country music, and white musicians played a substantial role in its development. These factors resulted in a particular musical aesthetic that centralised authenticity above all else and that gave free rein to expression. Southern soul’s musical DNA insisted on a core genuineness, in the playing, production and performance, that would entertain no artifice and that was in no hurry to adopt new musical styles or embrace new musical technology.

While other late 60’s/early 70’s soul artists were pushing forward with social commentary lyrics, wah wah guitars, synths, extended vamps and incorporating jazz or Latin influences, Southern soul took an unhurried, more conservative approach to its development. In fact, that un-hurriedness could be seen as a defining characteristic of much of Southern soul, a genre that could be slow and brooding or high-tempo and steaming, yet somehow often seemed inherently laid back, as though the simmering Southern temperatures had forged a distinctly relaxed musical aesthetic.

All this is not to say that Southern soul didn’t progress. By the early seventies, the Hi label had perfected a cleaned-up take on the genre — typified by Al Green’s Let’s Stay Together — with muted drums, sweet strings and an up-close production where every single musical element is clear in the mix.

In the decade that Southern soul peaked — broadly speaking from the mid-sixties to mid-seventies — the genre made a significant musical journey, from the greasy, gutbucket grooves of Otis Redding’s Stax recordings and Aretha’s church-influenced classic album run, to Al Green’s soft, accessible, intimate recordings. In the process, Southern soul gave us a catalogue of songs both warm and joyful and deep and mournful, an embarrassment of musical riches containing some of the most welcoming but also most uncompromising black music of the twentieth century.