The story of Anatolian Rock is usually told starting in the 1950s, when Turkish musicians first began mixing Anatolian folk with Western pop and electrified instruments. But while that is when this kaleidoscopic style first started taking shape, it helps to go back a few decades to 1923 to really understand its roots.

For centuries Turkey was the heart of the Ottoman Empire, one of the biggest and most enduring in history. The Empire was based on Islam and over time it absorbed the culture and customs of the Islamic societies it ruled over, and even evolved its own style of classical music. But after centuries of decline the Ottoman Empire collapsed and in 1923 was replaced by the Turkish Republic which through the teachings and a policies of Atatürk, “the founding father of Turkey,” moved away from its Muslim identity and towards a vehemently secular and modern one.

The creation of modern Turkey was a real exercise in state building, carried out through a series of political, economic, and cultural reforms, which included turning away from the classical music of the Ottoman Empire. At one point Turkish classical music was even banned, and the fanciest ballrooms in the country tried (unsuccessfully) to entice people with western jazz and waltzes. But rejecting Ottoman classical music, with its distinctive Sufi features, didn’t mean rejecting all Turkish music: the folk music of Anatolia (the Asian part of Turkey), which came from the Aşık tradition (Aşıks are Turkish bards known for the poetic lyrics accompanied by saz compositions), was seen as a “pure,” pre-Islamic form of Turkish culture, and thus was promoted and encouraged. Soon, the sounds of the ney flute, bağlama, and kemençe began filtering back into Turkish popular music.

Fast forward a few decades and by the 1950s Turkish airwaves were filled with European and American surf and rock’n’roll, inspiring Turkish musicians to pick up their electric guitars. Initially they mostly covered Western songs and sang in English (even Erkin Koray, who went on to be one of the founding fathers of Anatolian rock, started by playing Elvis Presley covers, and one of his first hits was the English language “It’s So Long”), but soon started translating lyrics into Turkish and incorporating Anatolian rhythms and instruments.

There are many fascinating parts to the story of Anatolian rock, but the role of the Altin Mikrofon Talent show has to be one of the most surprising. The talent show ran between 1965 and 1968 and had very specific rules: the artists who competed in the “pop” category had to compose their own songs in Turkish, or rearrange traditional Turkish melodies, but in a “Western” style and with modern instrumentation. The whole idea was to create a new style of Turkish popular music, based on Anatolian tradition but with a cosmopolitan outlook and approach. People who went on to become stars, like Erkin Koray, Moğollar, and Cem Karaca, cut their teeth on the show.

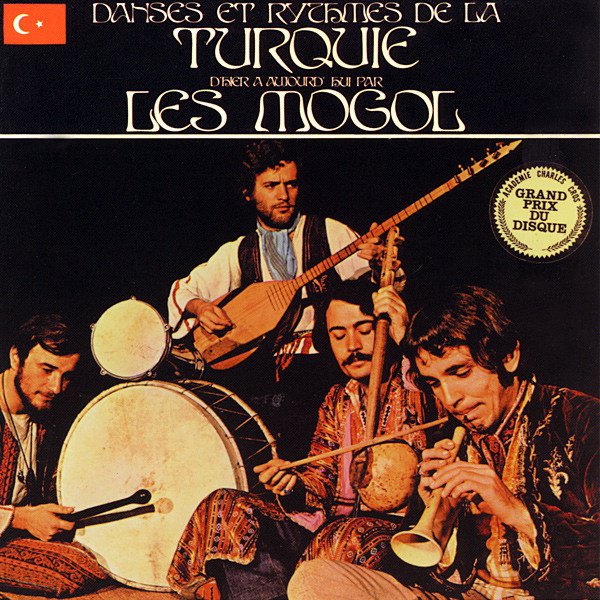

Initially this new hybrid reflected the pop and rock’n’roll sounds coming from Europe and the US, but during the psychedelic revolution of the 1960s Turkish bands began integrating the bağlama and davul while their British and American counterparts were using the sitar and the tambura. In the late 60s and early 1970s Erkin Koray abandoned his rock’n’roll roots and released a series of psychedelic 7” singles, starting with the swirling Anma Arkadaş and culminating with his psychedelic masterpiece, the 1974 album Elektronik Türküler. Moğollar, who in 1971 released the very successful modern folk album Danses et Rythmes de la Turquie, began to move away from their traditional, folksy sonorities and aesthetics in favor of a more psych rock identity and sound.

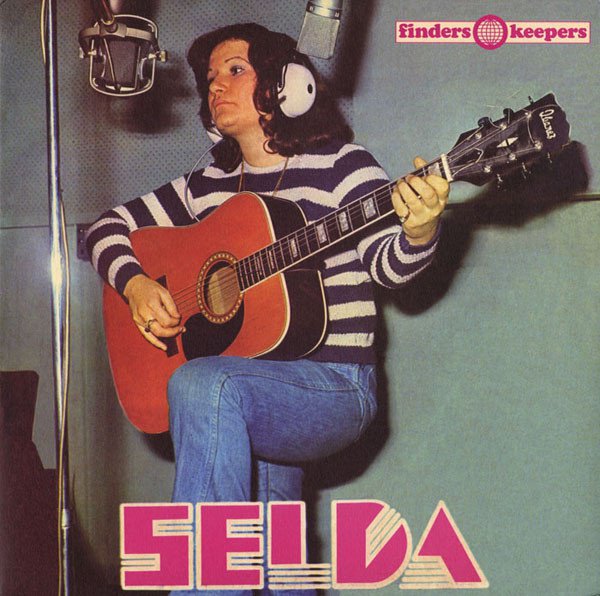

By the mid 1970s, against a backdrop of political turmoil and violence, psychedelic rock became the sound of the left wing resistance, with artists like Selda Bağcan and Cem Karaca penning lyrics that were openly critical of the state and the nationalist, right-wing squads it sponsored. Although the rock scene was flourishing, the country was collapsing, and on September 12, 1980, the Turkish army overthrew the government. During the military rule that followed the coup musicians were subject to censorship and banned from playing, many fled the country, and the scene all but came to an end.

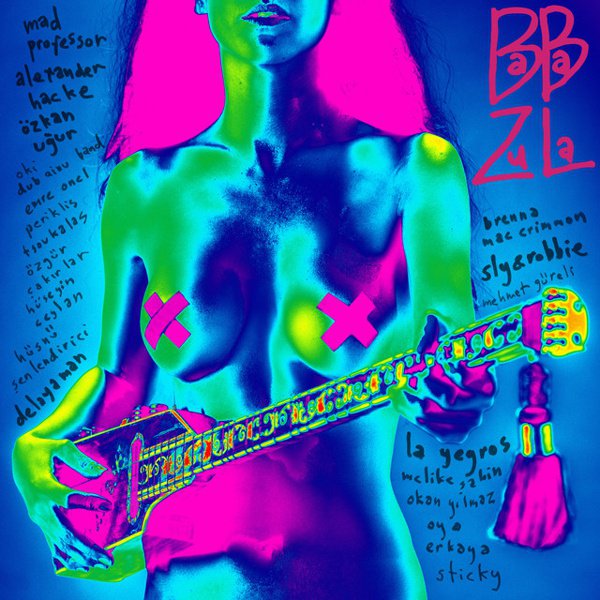

But the same strange alchemy that had given birth to Anatolian rock never really disappeared, simmering below the surface for almost two decades. Already in the 1990s some of the legendary 1970s bands began reuniting, and new groups like Baba Zula emerged to take up the baton.

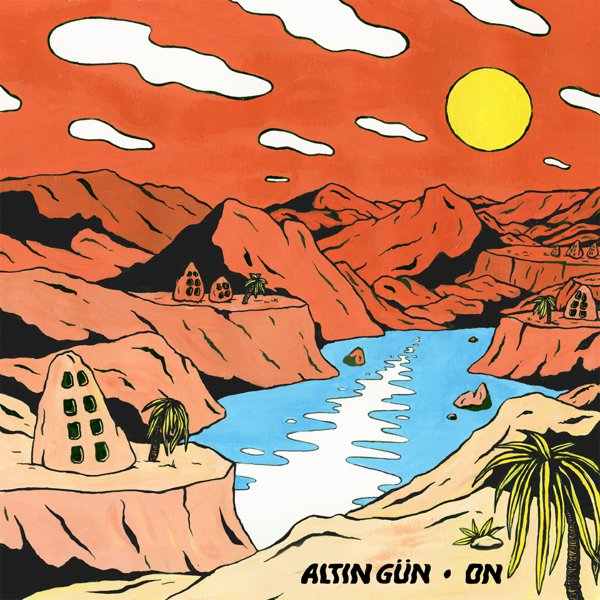

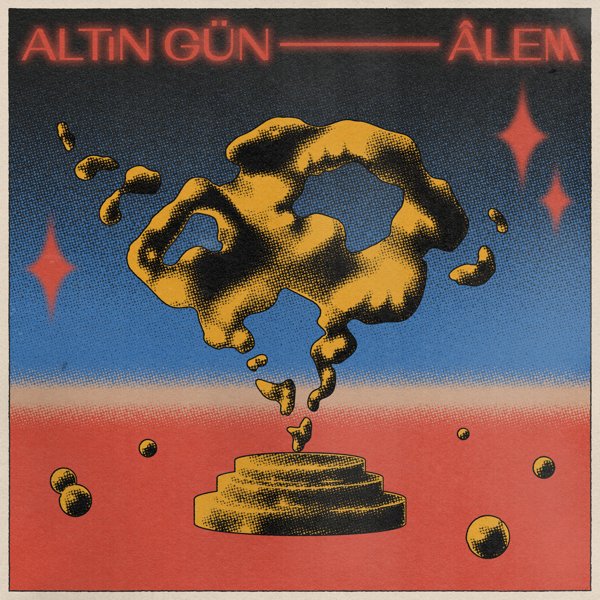

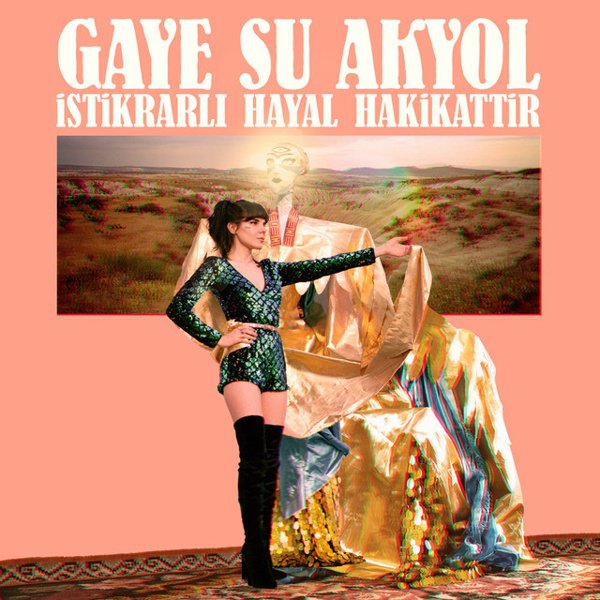

Since the early 2000s there has been a real renaissance of Turkish rock, a term which has now come to signify the mix of any “Western” style, from prog rock to funk, disco, and psych, with Anatolian folk music. But rather than being nostalgic tribute acts, artists like Altin Gün, Gaye Su Akyol, and Derya Yildirim and Grup Şimşek are able to move the sound forward with their synthesis of traditional and modern sounds.