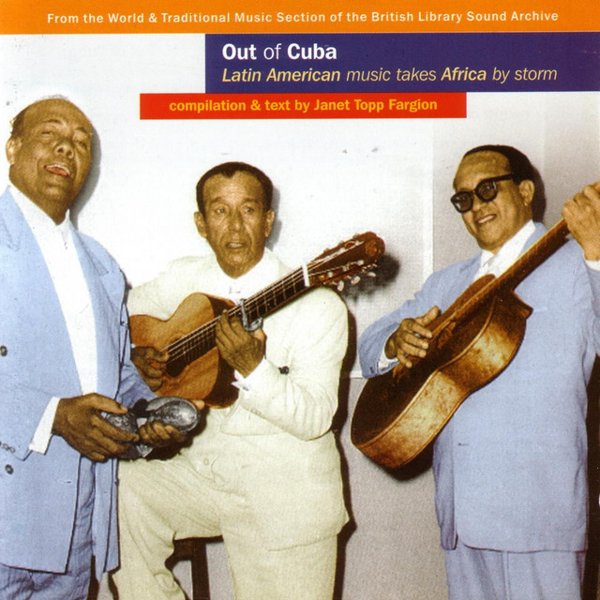

For centuries African sounds and rhythms have been flowing backwards and forwards across the Atlantic, reshaped and renewed by their encounters with new cultures. But while the influence of African music in Latin America and the Caribbean is well known, the same can’t be said for the opposite. Yet the musical cross-pollination has been rich and vibrant on both sides of the ocean.

Cuban music for example is heavily influenced by African culture: over three centuries an estimated 1.3 million slaves were taken to Cuba from different regions of Africa, and by 1840 over half of the population of Cuba was of African descent. The enslaved people never relinquished their culture, and what we know today as Cuban music is based on the complex polyrhythms and call-and-response songs of the Yoruba (from present day Nigeria), the Congolese, the Dahomey (from Benin), and dozens of other ethnic groups from across the continent.

But these new Afro-Cuban sounds quickly found their way back to Africa, through the travels of Caribbean and African sailors and slave trade’s vast networks, and by the 1930s the cultural tide began flowing back towards Africa. With Europe in the throes of the Great Depression, in 1933 Gramophone began repackaging hundreds of Victor’s Cuban recordings for the African market as the African GV series. Among them was “El Manisero‘’, a hugely popular son-pregón sung by Antonio Machín that arguably shaped musical styles across the African continent, and that over the years would be covered by dozens of African bands.

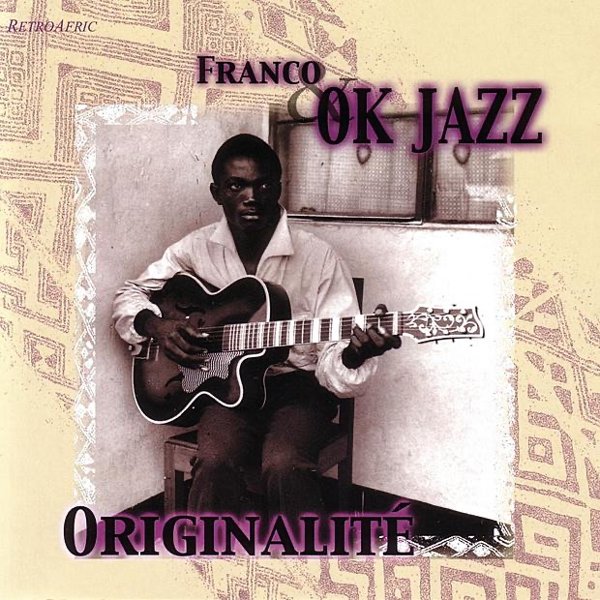

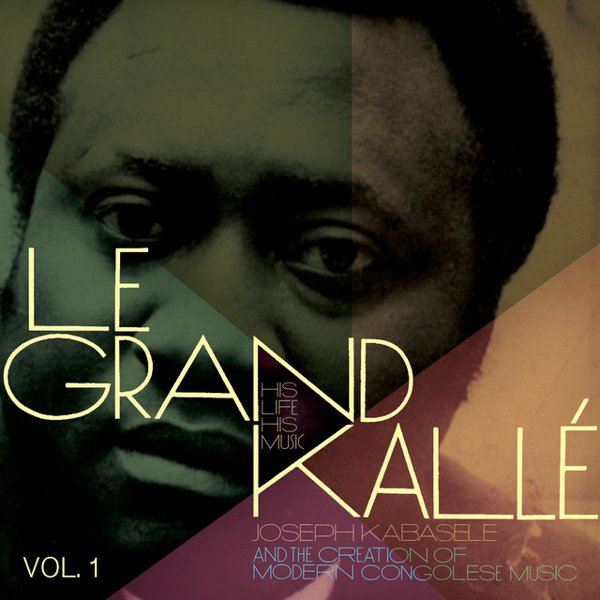

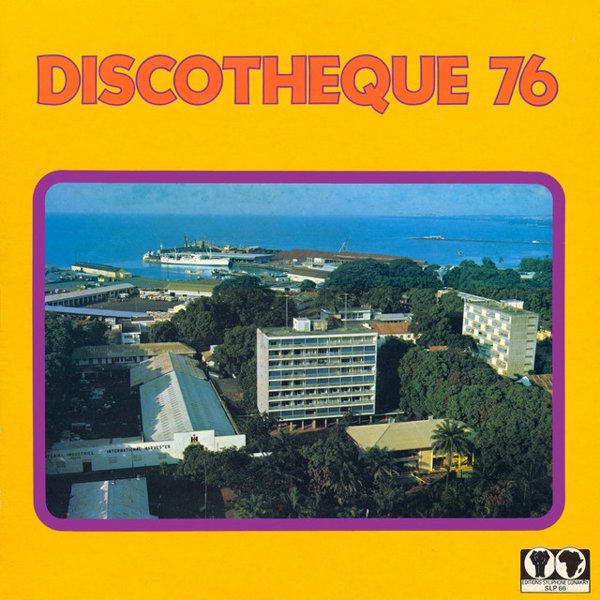

These Cuban songs, with their familiar African rhythms, quickly became the favorite in nightclubs in Dakar, Accra, Cotonou, and Ouagadougou, and bands began covering the most popular hits, often singing phonetically in Spanish. In Congo the GV records had a profound impact on musicians and inspired the emergence of the Congolese Rhumba, a style that in time has become such a intrinsic part of Congolese culture it is protected by UNESCO, and has in turn had its own huge impact on music in other regions of Africa.

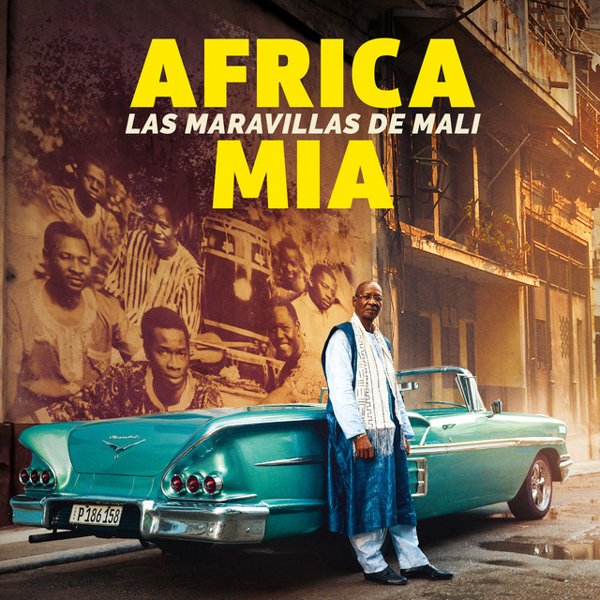

The end of colonization also gave Cuban culture a new level of significance in many African countries. With Ghana and Guinea gaining independence in 1958, Mali and Senegal in 1960, and many others between 1960 and 1962, the anticolonial struggle coincided in many cases with the 1959 Cuban revolution, when Fidel Castro came to power after overthrowing an illegitimate US-backed government. Castro’s anti-imperialist ideals resonated in African countries that were fighting to free themselves from colonial rule, or that had recently become independent but were trying to break free of their cultural shackles. Sensing the opportunity, Castro developed diplomatic and cultural ties with African countries by sending humanitarian aid and Cuban professionals such as doctors and teachers to Africa, as well as setting up scholarships for African students to study in Cuba. African students in Cuba set up their own bands, and Cuban bands like Orquesta Aragòn, Pancho Bravo, Orquesta Jorrìn and Orquesta Sensacìon toured extensively in Africa.

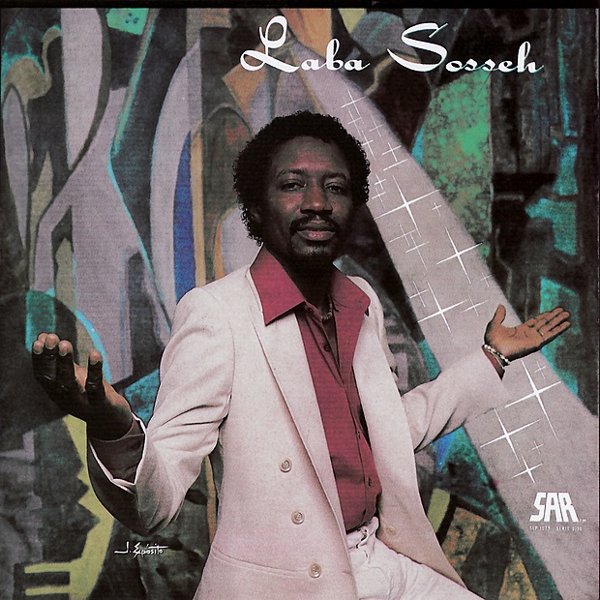

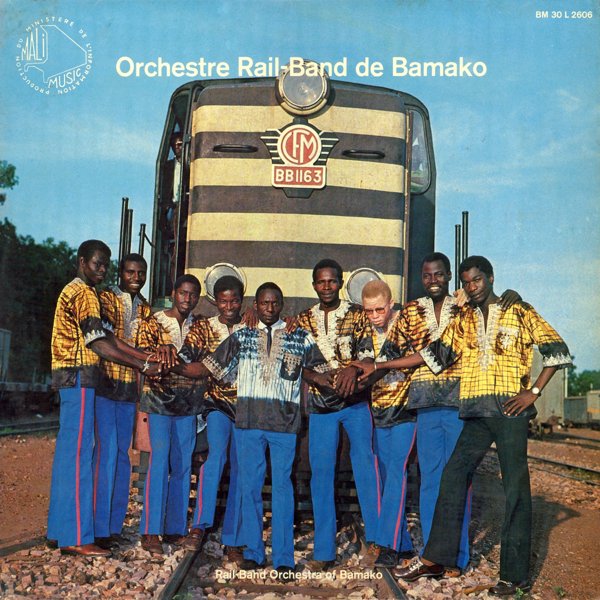

In the context of post-independence, Cuban music represented a viable alternative to Europe’s hegemonic models of “modernity.” It retained traditional African elements yet sounded modern, and symbolized a form of much desired urban cosmopolitanism while being something other than European. Dancing to Cuban music gave young Congolese, Senegalese, Beninese, Guineans and Malians the opportunity to be part of a modern world, while still embracing their anti-imperialist stance. As the newly independent states worked towards becoming nations and building new national identities, musicians moved away from mere imitation of Cuban music and began to integrate local instruments and folkloric elements into their music, working towards a process of indigenization.

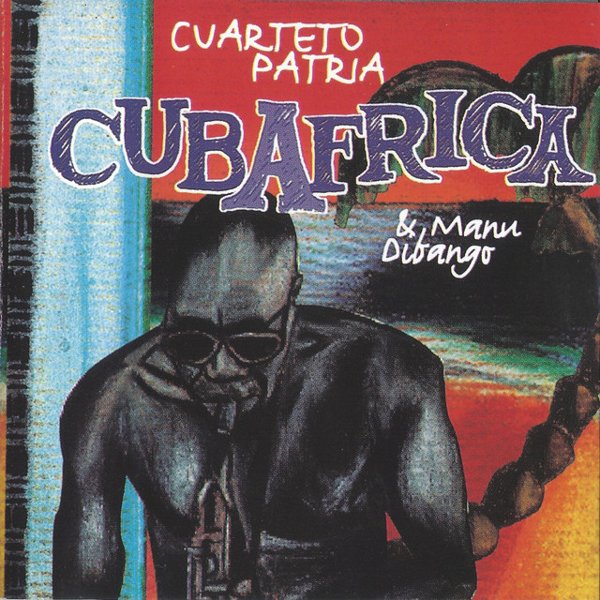

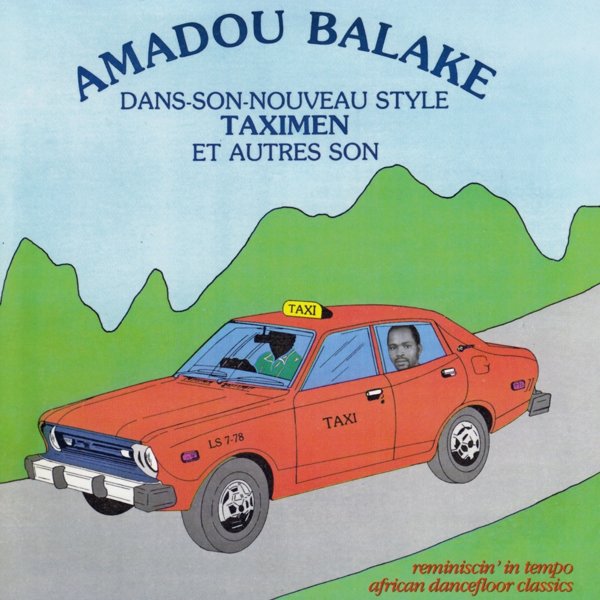

Today, across West and Central Africa, Cuban music can still be heard blaring out of taxis and roadside bars, and the same bands that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s (that have remained popular or in some cases been “rediscovered”) continue to play their unique melange of local and Cuban styles. Collaborations between Cuban and West African musicians have continued to thrive: Africando is a project formed in 1992 that unites New York based salsa musicians and West African vocalists; in 1998 Cameroonian great Manu Dibango recorded the album CubAfrica with Cuban artist Eliades Ochoa; and Cuban pianist Roberto Fonseca and Malian singer Fatoumata Diawara have been recording and touring together for years.