For a label that’s been releasing consistently trend-warping and creatively daring albums for over three decades, something about Ninja Tune still feels a little frivolous — not superficial or inane, but at least a bit refreshingly unserious. In a UK-rooted post-rave landscape dominated by similarly-minded peers and successor labels from Warp to Mo’Wax to Planet Mu to Hyperdub, the spirited sense of irreverence that fueled much of Ninja Tune’s initial ascent still looms as a definitive part of dance music history. That irreverence was fueled by the liberating potential of so many Wired-ready ’90s-futurist concepts: culture-jamming multimedia manipulation, a powerful belief in the aesthetic recontextualization that came from sample-based composition, and a por que no los dos refusal to adhere to punk’s old “fuck art, let’s dance” binary. If that meant that the road to some of the deepest avant-dance albums of the last ten years ran through an early wave of comedic turntablism, quirky acid jazz, and some of the most British-eccentric takes on hip-hop production thinkable, that just makes the entirety of Ninja Tune’s whole 30-plus-year corpus feel even more astounding.

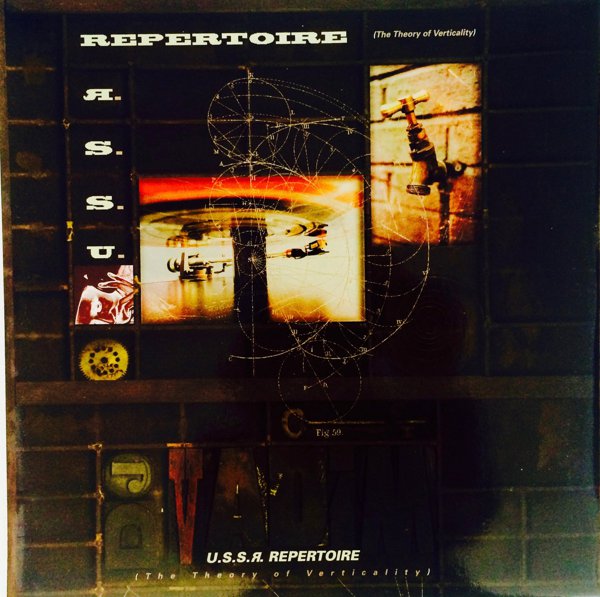

Established in 1990 by Matt Black and Jonathan More of cut-up wizards Coldcut, Ninja Tune first found its footing in the same hip-hop-besotted DJ circles that Coldcut helped popularize in the UK to start with in the late ’80s. Jazz Brakes, a series of beat-battle and sample-fodder weapons released under the artists-collective aegis of DJ Food, provided the bulk of the fledgling label’s sales and attention in the first half of the decade, and served as integral components of the assorted sounds that would define UK sample-based music — downtempo, acid jazz, and trip-hop — for the remainder of the ’90s. By the decade’s end, their most reliably progressive-minded and exciting artists, from hip-hop-rooted The Herbaliser to drum’n’bass superdeconstructionist Amon Tobin to the filmic evocations of Jason Swinscoe’s symphonic jazz auteurism as The Cinematic Orchestra, staked a strong claim somewhere between the crowdpleasing go-go dance party hedonism of big beat and the frantic rhythmic iconoclasm of IDM.

But while the cast of characters that made up the label’s early efforts would remain pivotal to the label for decades, Ninja Tune benefited greatly from an ability to take the traditional community-building base of radio shows and dance nights and expand them into something that fit the global-village potential of the early internet. Coldcut’s futurist fascination with music as just one component of a multimedia experience would soon expand into a DIY-cultivating mission to democratize the creation of electronic music. This manifested in a cross-disciplinary incorporation of “video sampling” and interactivity as part of their live shows and home-listening experiences, abetted by frequent collaborations with Hex Media and their successors Hexstatic in creating simple, fun music creation software and CD-ROM playthings. It was the old ’70s punk-fanzine “this is a chord, this is another, this is a third, now form a band” catalyst for a new generation and a new means of production.

It could get silly, and that was part of the liberating effect the label had. Stalwarts like the cartoonishly eclectic Mr. Scruff and comedy-scratch virtuoso Kid Koala approached their often complex and visionary work with an almost childlike unpretentiousness, which proved to be an accessible route to some of the label’s more outre and counterintuitive sounds. First-decade label-sampler compilations like 1998’s Ninja Cuts: Funkungfusion and 2000’s Xen Cuts embodied this feeling better than anything; having a wigged-out sample-collage by honorary paterfamilias Steinski or one of Luke Vibert’s manic funky-drummer breakdowns share space with a rising Brit-rap star like Roots Manuva or retrofuturist psych-jazz-fusion group Loka made it clear how holistic the label’s approach really was. And that’s before you even account for their history of offshoot labels — particularly the experimental-focused Ntone and the still-thriving art-rap imprint Big Dada Recordings — that made their already nebulous sense of beat music feel practically limitless.

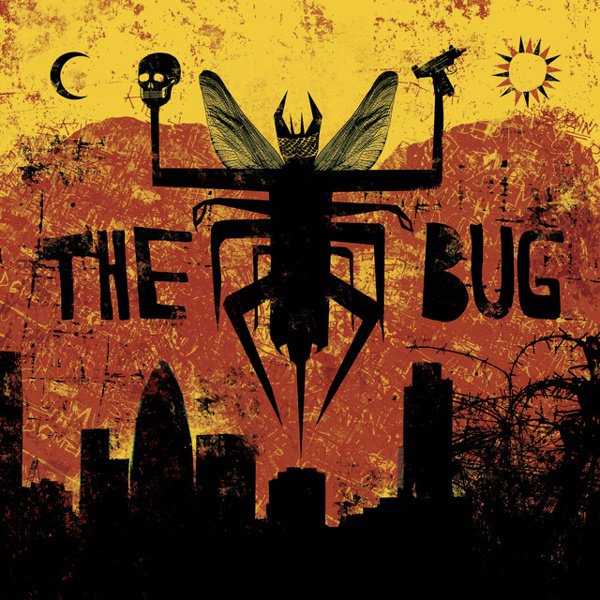

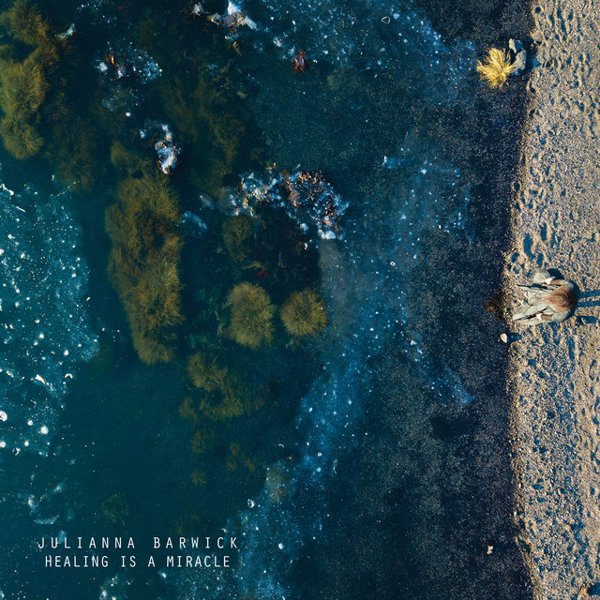

This could be why Ninja Tune weathered the industry-downturn 2000s so well — that, and their tendency to champion artists who the struggling majors wouldn’t even deign to touch. But while their sustainability through the aughts produced a good share of vital and exciting records, it was their expansion in the 2010s that elevated them from lingering survivors of the wide-open no-rules ’90s into a renewed pillar of cutting-edge experimental electronic music. This was thanks to distribution deals and co-signs with heir-apparent labels like Flying Lotus’ Brainfeeder and Actress’s Werkdiscs, combined with a litany of next-generation label signees that took Ninja Tune’s post-genre dance precedent to even deeper, more viscerally experimental places — think the percussion-rending clubland anxiety of Forest Swords, the glitchy warmth of Floating Points, and the prismatic smears of Julianna Barwick’s cathedral-of-the-voice ambient. Long may they cut.