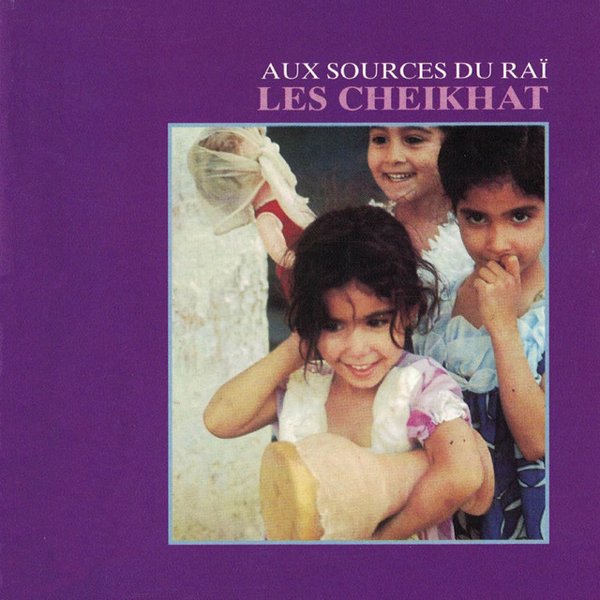

It’s no coincidence that a style as rebellious and eclectic as Raï emerged in Oran, a vibrant port city in northwestern Algeria where Arab, Berber, Jewish, and European culture has mixed for centuries. In classic port-city style, Oran was known for its debaucherous nightlife, for the nightclubs and bordellos where the strict rules that governed the rest of Algerian society were left at the door. It would have been impossible in the 1920s to see Muslim women performing for men in any other part of Algeria, for example. Rather than recite classical Arabic poetry, the cheikhas sang about the harsh realities of everyday life using crude and sometimes vulgar language, accompanied by drums and reed flutes.

The cheikhas usually improvised their lyrics, but always included their — often controversial — opinions on a current matter, or a piece of advice to the younger generations. The style of music became known as Raï, meaning “opinion” or “advice” in Arabic, and quickly became popular among Algeria’s working classes for its mix of irreverent vocals, Berber rhythms, flamenco, French cabaret, and gnawa. One of Raï’s earliest — and most enduring — stars was Cheikha Rimitti, who by the early 1940s rose to prominence with her salacious songs that celebrated sex, love, and hedonism. “I sang all the subjects back then. I sang about misery. I sang about love. I sang about the condition of women. I sang about ordinary life, concrete things. I sang the life I had seen, my own history” she said in a 2001 Afropop interview. But, she added, “Raï music has always been a music of rebellion, a music that looks ahead.”

The subversive force of Raï didn’t go unnoticed by Algeria’s government, and Raï musicians became personae non grata among parts of the country’s conservative society, so much so that Cheikha Rimitti, whose real name was Saadia El Ghizania, changed her name in order to protect her family from the “shame.” But with independence from France in 1962 Raï’s popularity only grew: though both Houari Boumédiène and President Ahmed Ben Bella sought to repress Raï, fearing its subversive potential and placing emphasis on the “Arab and Muslim” aspects of the new Algerian identity (with which Raï was at odds), Raï continued to flourish especially among the working classes. Musicians began replacing traditional instruments with sax, trumpets, pianos, and accordions, and Raï took hold among Oran’s youth.

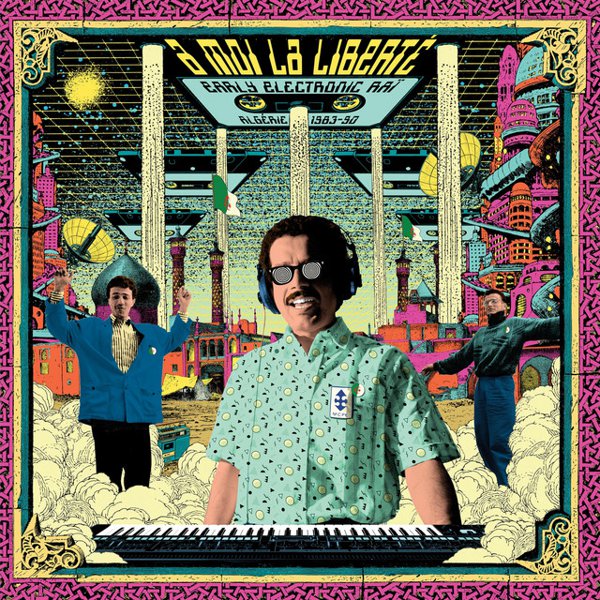

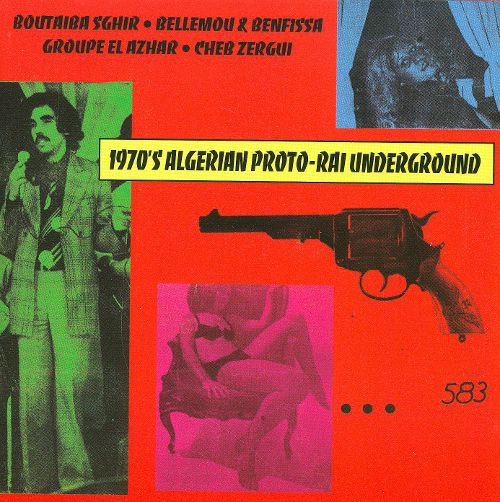

In the 1970s cassette tapes enabled musicians to record cheaply and sell their music widely, giving life to a whole new generation of musicians, and Raï spread across Algeria. New musical technologies also began changing the way Raï sounded: Ahmad Baba Rachid for example was among the first, in the late 1970s, to blend pop and electronic production in his music. In the late ‘70s a new government also changed its stance on Raï, recognizing it as an important part of Algerian culture, especially amongst young people. Though they still maintained tight control of lyrics, Raï was finally aired on radio, and in 1986 the government even funded the Oran festival.

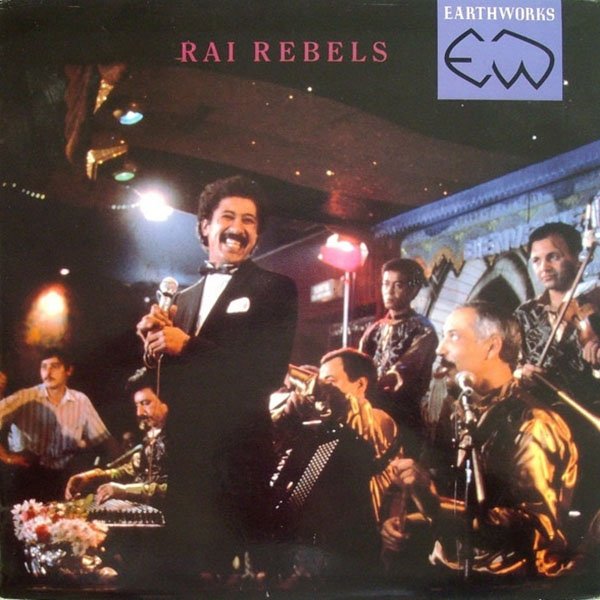

By the 1980s singers had abandoned the titles of Cheikh and Cheikha, and instead went by Cheb and Chaba to differentiate themselves from older musicians playing the more traditional style. They further incorporated synths, drum machines, and electric guitars into their music, and embraced a much more pop aesthetic. Raï became Algeria’s most popular dance genre, and the simultaneous rise of the “World Music” Industry propelled it to a global audience.

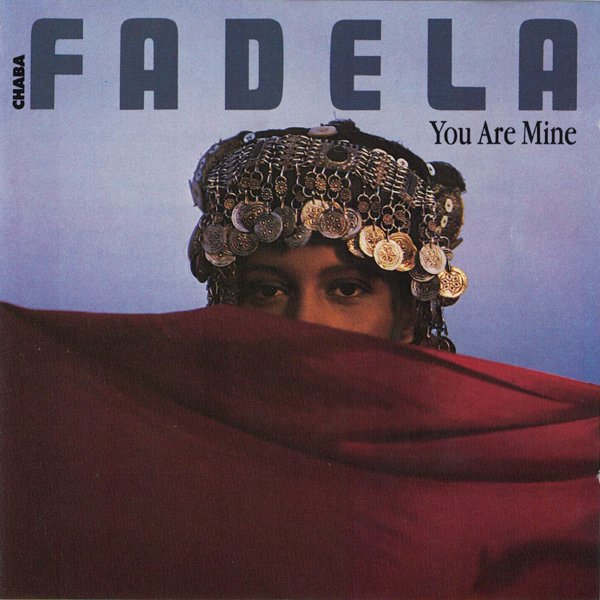

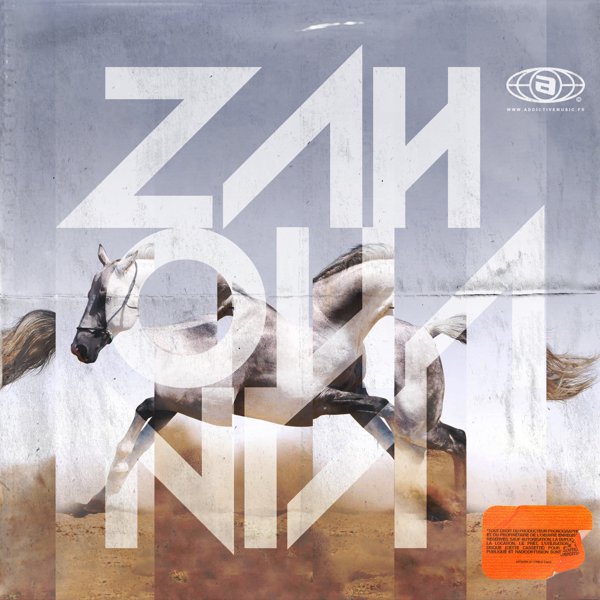

Raï superstars like Cheikha Rimitti, Chaba Fadela, Cheb Sahraoui, Houari Benchenet, Cheb Hamid, Chaba Zahouania, and Cheb Mami began touring the world. But no one would come to represent Raï on the globe stage as much as Cheb Khaled, the much-loved “King of Raï” who would become a controversial figure in Algeria.

His song “El Harba Wayn (To Flee, But Where)” became a protest anthem in 1988, a year that saw some of the country’s biggest anti-government riots and the death of hundreds of protestors, a sign of the bloody conflict that would break out three years later. Over his career Khaled would have a complicated relationship with the Algerian government, albeit not as antagonistic as usually depicted — in fact, it was originally Lieutenant-Colonel Hosni Snoussi, the director of the state-supported Arts and Culture Office, who supported Khaled and invited him to perform at the Festival de la Jeunesse pour la Fête Nationale in Algiers in July 1985, an major event which helped boost his career.

After a brief period of openness however the Algerian government once again tried to suppress Raï in the wake of the 1988 riots, tightening the cultural policies which promoted classical Arabic culture at the expense of the multi-cultural aspects of Algerian culture, excluding regional dialects and languages like Berber from state-controlled media. Raï is sung in Warhan Arabic and borrows words from Spanish, French, and Berber, so most Raï music was banned from state radio, a policy that, coupled with the bloody civil war that took over the country in the early 1990s, led artists like Cheb Khaled to leave Algeria for France.

His 1992 hit “Didi” made Khaled (he dropped the “Cheb” title from his name in the early ‘90s) an international superstar, and gave Raï an unprecedented global reach. But while artists like Khaled and Cheb Mami played to arenas around the world and collaborated with global superstars, Raï in Oran continued to evolve, influenced by an even wider array of styles as the cell phones and internet connections became more available. Even U.S. R&B and dancehall have bled into modern Raï production — just listen to Cheba Wahida’s hypnotic party bangers. As the true music of the people, Raï never needed big promoters, festivals, or official support in order to thrive. First through live performances, then through cassette tapes and now through social media and bedroom producers, Raï has continued to flourish outside official channels.