Outside of personal razors, barrel-aged whiskey, and light beer (and of course, menthols), “smooth” as a descriptor is pejorative. It’s even less desirable when deployed to describe music. It gets cast as the diametric opposite of authenticity, hardness, urgency, truth; it becomes synonymous with wallpaper, docility, selling out, the status quo, corporate. Call jazz “smooth” and the connotations are anathema to the form: bland, phony, toothless, mindless, lifeless. For generations, smooth jazz belonged in the dustbin of history alongside new age, easy listening, and Muzak, genres unworthy of reconsideration, much less a consideration in the first place.

But new age and its ilk have undergone a reappraisal in the 21st century, while smooth jazz remains unreformed. As late as the reform-minded 2007’s A New History of Jazz still brushed off smooth, labeling it as “the antithesis of improvisation, collective interaction, swing, soul, or heart.” Even with the well-received doc Listening to Kenny G, it still felt like we were laughing at the poodle-haired multi-millionaire, not with him. Blame it on chiropractic waiting rooms, dental x-rays, malls, being put on hold, or waiting for your pedicure to dry, but “smooth” still suggests purgatory. (Or as this Far Side panel suggests about jazz players, hell.)

If fiery spiritual jazz roars, rages, and emotes at one of the musical spectrum, with “swing, soul, or heart” right in the middle, then smooth breezes and toots along on the other side as its extreme opposite. But is it the opposite? To only hear the energy and bustle of jazz is to miss its inherently more mellow aspects. It’s there when the band cools one in a set, or when a horn player proves his or her mettle across a gentle ballad, when a certain lightness is required to convey the mood. Maybe spiritual jazz and smooth jazz might not be so different after all?

As writer Francis Gooding argued in “I Dream of the Sea: Smooth Jazz and the Radical Tradition,” an eye-opening essay for the Finnish We Jazz Magazine last year: “Smooth is in fact the musical successor of the spiritualized and experimental jazz avant-gardes of the late 1960s and 1970s. Far from being formally retrograde, it was formally innovative, signaling among other things a new interest in the value of changes, a reconsideration of the nature and purpose of the solo, and the forging of new connections for jazz between soul, boogie, early rap and house. It also linked into wider musical developments in the Caribbean and the wider Black Atlantic diaspora.” In his estimation, “smooth” cast off the critical burden and intellectual aspirations that had shadowed jazz since the 1940s: “Smooth finally managed to shut the white hepcat out.”

“Smooth” didn’t come as a descriptor until the late ‘80s, coming out of market research conducted by the industry, when the Smooth Jazz Network appeared alongside Jones Radio Network satellite station creations like Good Time Oldies. Prior to that, it had fallen under tags like “lite-jazz” or “jazz-pop.” Neither name stuck except in the craw of critics, collectors, and jazz cognoscenti alike. While they had long fetishized high-minded jazz, extolling the virtues of serious album works of the late 1950s and ‘60s, they gave short shrift to the more popular jazz fare of the day. While soul-jazz and albums by Ramsey Lewis, Ahmad Jamal, Jimmy Smith, and Wes Montgomery sold by the truckload, they were derided as light-gauge, not nearly as profound as Sonny Rollins’ The Bridge, John Coltrane’s My Favorite Things, or Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come.

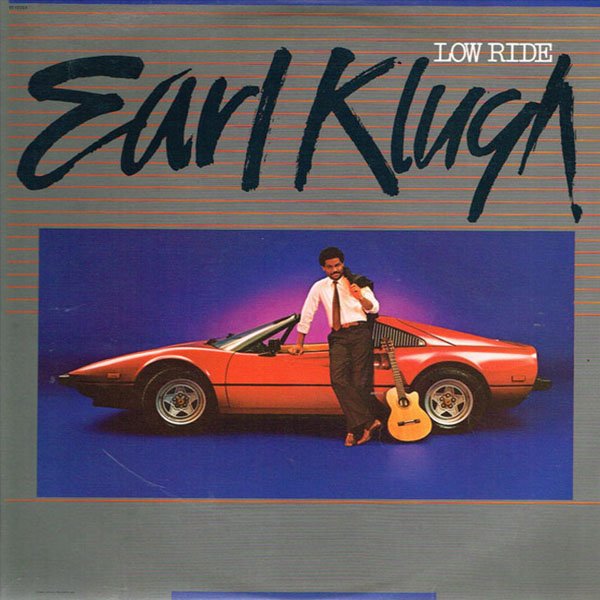

The hipster-built ghettoized mainstream continued on into the 1970s. Fusion might have begrudgingly become acceptable in some quarters (especially Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters, Mahavishnu Orchestra, and Weather Report), while its slickest practitioners (think Spyro Gyra, Bob James, Earl Klugh, releases on the extra-slick Kudu label) were still perceived as dreadful dreck. (I also hear the roots of smooth in the productions and arrangements of the Mizell brothers, who favored hummable hooks, R&B choruses, and arrangements that folded the individual soloist into a streamlined, holistic groove.)

At the same time, smaller independent labels like ESP-Disk, Strata East, Black Jazz, and Tribe became increasingly fetishized and revered. These were albums that didn’t sell well, or garner much airplay, or help sustain these artists so that they could build a career. So where could they turn? Look closer at some players who cut smooth albums and you’ll notice many crucial figures of 1970s independent jazz there.

Azar Lawrence, who served as sideman for the likes of Miles Davis, McCoy Tyner, and Elvin Jones, cut a slick bit of smooth jazz-boogie with Shadow Dancing. Philly flamethrower Byard Lancaster roared with the likes of Sun Ra and Sonny Sharrock, but he also blew smooth and groovy on My Pure Joy and on Napoleon Cherry’s Rosetta Stone of smooth, Cool Waters. The rare, Latin-tinged Caribbean Breeze is an album made by the duo of Omar Hill and Art Webb, gents whose resumes include Pharoah Sanders, Cecil McBee, and the Sounds of Liberation. Black Jazz alum Calvin Keys self-released two beautiful albums in Maria’s First and Full Court Press. Tribe prime mover Marcus Belgrave cut the smooth single “Two Ships Passing in the Night” by 1985. And then of course, there’s Miles himself, pivoting to the slicker sound of Black radio in the 1980s, ensconced in misty synths and Marcus Miller’s silky bass, covering Michael Jackson and Cyndi Lauper in the process.

Gooding detects a connection between the rise of sophisti-pop stylings of Sade and Luther Vandross in the decade and how smooth mirrored that trend. “Not since the days of the great vocalists and instrumental balladeers of the swing era had jazz dwelt at length on romantic love in the here and now – sex, companionship, and the long evening hours of happiness with the one you love,” he writes. “This is what smooth chose to speak on.”

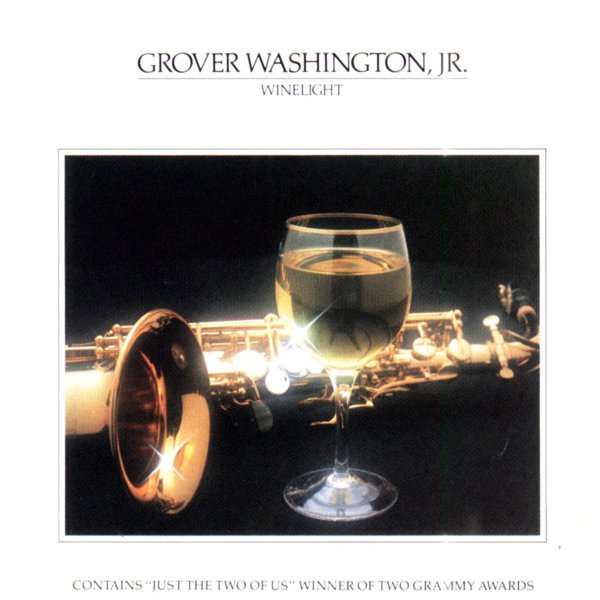

Smooth has many characteristics beyond flickering candlelight, rose petals strewn across silk bedding, and an oaky Chardonnay. The sax or trumpet (or better yet, soprano sax and flugelhorn) takes on the role of vocalist, swaying closely with the melody rather than ranging far from its contours. Rather than spontaneous group interplay, smooth favors pre-recorded instrumental beds, with the soloist set atop it, an aspect certain to rankle most jazz fans.

More often than not, there is more than one cover of instantly-recognized hits. But venture beyond those hits, beyond that sense of the music as mere “wallpaper” or hold music, and smooth gets odd and quirky fast. You can hear how a canned handclap, a synth bass ostinato, or maybe a sensuous vocal hook gets purred and, track by track, some strange new song comes into focus. It’s not quite R&B or quiet storm, not jazz in the traditional sense, not quite disco or club music; it’s smooth.

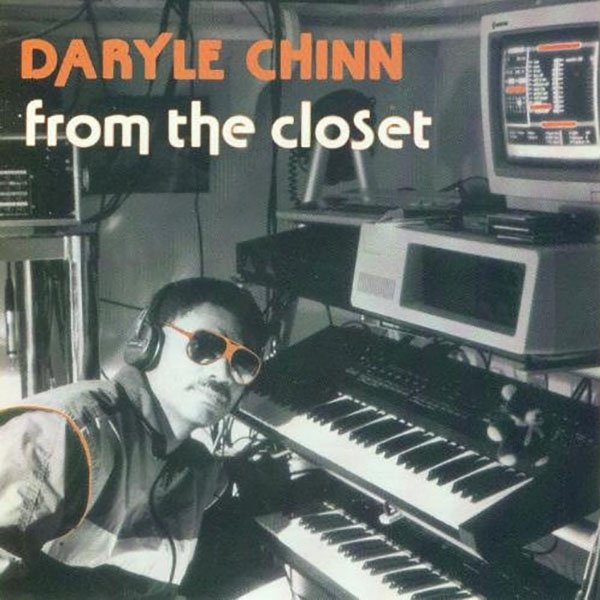

Nascent home recording technology is crucial to the rise of smooth, including synthesizers, drum machines, MIDI, samplers, and digital recording techniques. This new tech made it possible for certain players to create everything all by themselves, a late 20th century update of the one-man band. Smooth benefited from home recording studios and as a result, a cottage industry of self-released music flourished.

Just like early house, electro, and hip-hop producers of that same era, smooth players no longer needed to book out expensive studios to put their ideas down to tape. Perhaps because the presets and canned handclaps and snares hit similarly across genres, there’s also a willingness in smooth to intermingle with these other forms: quiet storm, downtempo house, new jack swing, even hip-hop. Listen closely and productions made by Chicago house music legend Larry Heard, the lithe albums made by Sade and Luther Vandross, and select smooth cuts sound more like first cousins than total strangers.

In Natalie Wiener’s interview with smooth innovator George Shaw, a trumpeter/ flugelhorn player who “integrated synths and drum machines in a way that anticipated plenty of 21st century music,” it reveals how smooth was really slick. Shaw may have been making what he calls “musical wallpaper,” but he was in on the joke, until you realize he got the last laugh. His music graced elevators, grocery stores, hotel lobbies, doctor offices, and even made it to an Apple ad. Unlike generations of jazz players who relied on club owners and promoters and record labels for cash, smooth players wound up getting paid. Radical indeed.