Recommended by

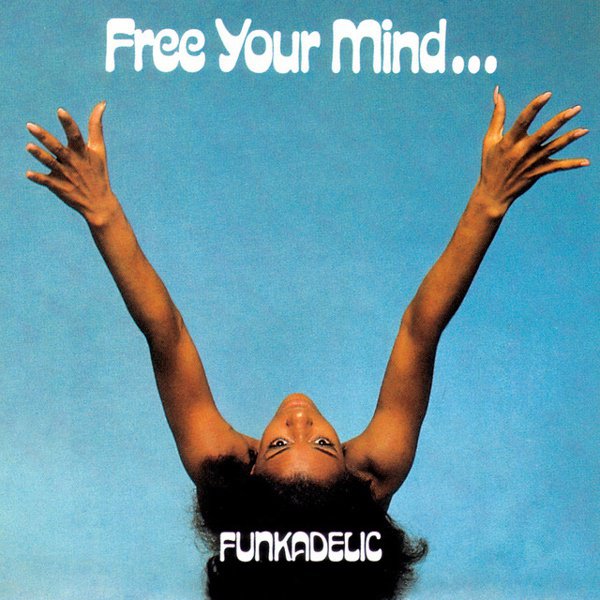

Free Your Mind…And Your Ass Will Follow

Perched in the crook of a joint connecting their gauntlet-toss self-titled debut and the heaviest-possible-funk of Maggot Brain, Funkadelic’s sophomore LP and their second of 1970 tends to be remembered best for its title — which, damn, what a title, and the song that shares it is a real wig-out oh, they’re completely acid-fried watershed, too. Those less patient with that opening salvo’s brand of freakout stargate-sequence funk can still find plenty to love, though; for an album apocryphally envisioned as a product of nonstop LSD consumption, the best bits cohere with a sort of paradoxical sloppy clarity that betrays George Clinton’s absolute mastery of blues and soul (and heavy metal while we’re at it). It’s like they fell into a fugue state, played out of their minds, and after they came down they’d discovered they’d given us a string of counterintuitive miracles: a song about spending your tax return on getting fucked all the way up (“Friday Night, August 14th”) that goes to drum-reverb echo dungeons that Lee “Scratch” Perry wouldn’t spelunk for another few years, followed by a bitter reckoning with everything capitalism’s wrought (“Funky Dollar Bill”) that beat the O’Jays to the gut punch, and then into “I Wanna Know If It’s Good to You?” and its post-Jimi declaration that there’s a thin line between love and dilating your third eye. (Its origins as a 45 make the album version a bit of a no-clutch gearshift, but the LP’s splice of the vocal and instrumental sides makes for an abrupt look out here I come wall-of-squall transition that sounds like the funk-jam equivalent to everything that happens after Lou Reed yelps “and then my mind split open” on “I Heard Her Call My Name” — only better because the apocalyptic noise is coming from Eddie Hazel’s guitar.) All that’s left to account for is the plastic-and-aluminum blues of “Some More” (featuring even more proto-dub refraction and the top-tier metaphor “I’ve got headache in my heart/Heartache in my head”) and the lysergic player-hater glories of tape-warping closer “Eulogy and Light,” and you’ve got an album that stands as an early but fully-formed (and wonderfully malformed) example of the Mothership’s fully operational powers.