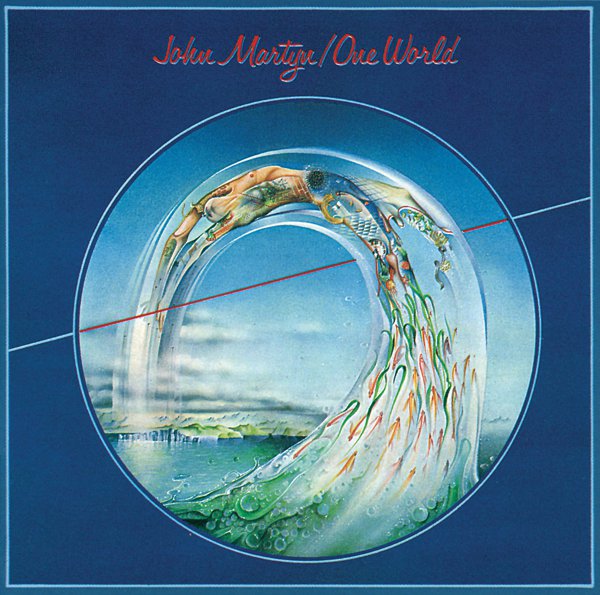

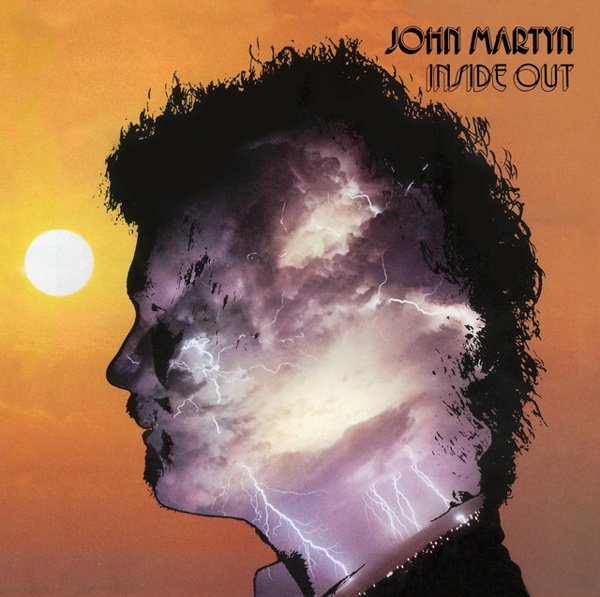

One World

Martyn escapes to Jamaica with Chris Blackwell for several months, commencing with Lee Perry and pissing off a lot of locals. One World was recorded on Blackwell’s Woolwich Green farm in Berkshire, using the Island Mobile truck, with Blackwell producing for the first time. As engineer Phill Brown described it in his memoir, the house “was almost totally surrounded by a flooded, disused gravel pit—a large lake with a house in the middle.” Brown set up mics on the edge of an adjoining stable, capturing the output of a PA pointed out across the water. “The outside mics not only picked up the guitar coming back across the lake,” Brown writes, “but also recorded scurrying animals, birds and the sound of water lapping at the lake’s edge.” Danny Thompson appears only on two tracks, and was soon gone from the Martyn orbit. Steve Winwood appears as does Andy Newmark, Lee Perry, John Stevens, Rico Rodiriguez, and a host of instrumental killers. Running on a steady diet of opium, Blackwell and Brown and Martyn worked surprisingly quickly. The result is the final and possibly greatest album in the Spacey Martyn catalog, right before Bevereley quite rightly divorces Martyn and he heads off into the next stage of his career. “Dealer” is a wild and tense number, soupy and bony at the same time. “Smiling Stranger” has been cited (semi-convincingly) as a precursor of Massive Attack, consisting mostly of wobbling bass, Moog, tabla, and a gorgeous string arrangement. (I often think Martyn’s greatest innovation in the Seventies was eliminating the drum set backbeat.) Martyn was as fond of drum machines as he was echo and wah, and you hear it on “Big Muff,” his goofball collaboration with Perry, which bears no credit for Perry, though many stories confirm Perry was running around doing his thing. The masterpiece here is “Small Hours.” Riding his volume pedal, and working with Winwood’s Moog, Martyn just levitates for almost ten minutes, barely playing. As quoted in Graeme Thomson’s magnificent Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn, Blackwell said the song is “like Gil Evans. It’s in the top three of records I’ve ever produced. When I say I produced it, I mean I was there, so I get the credit, but the musicians produced that music. It just floats, and the sound of the geese on the lake and the train going by—it’s so alive. I remember the whole experience as pure magic. The atmospherics were so great, and he was so excited about how it sounded, that he’d captured this fleeting magic. Winwood’s playing is unbelievable. It’s like leaves [falling] from a tree, the way he plays. It’s one of those magical things.”