Recommended by

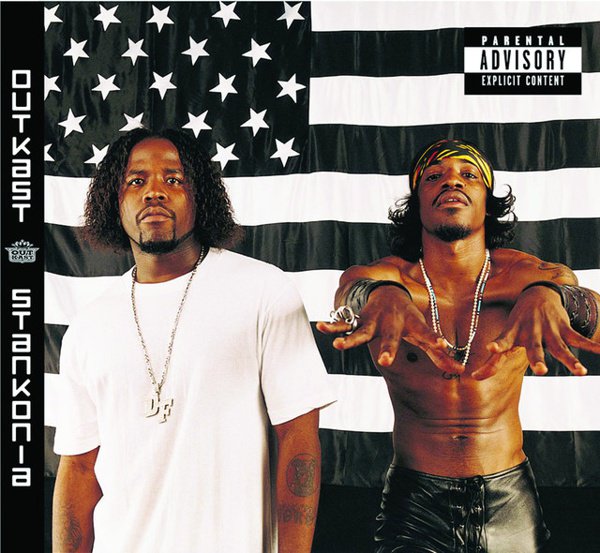

Stankonia

Stankonia is the Atlanta duo’s last truly great album, or at least the last album that had equal parts era-defining smashes and long-lasting deep-cut resonance from start to finish. It feels transitional in retrospect, as Big Boi and Dre were becoming more autonomous in their productions, with only scattered input from the Organized Noize crew that built the sound of their first three albums. But their spirit of experimentation and adventure hadn’t yet driven a split-double-album wedge between the two, and there weren’t any critical illusions of their “transcending” Southern rap as much as they were just adding new routes to it. You can tell just from the big hits: the fast-forward hyperarticulation of “B.O.B.”’s drum’n’bass-with-a-drawl, the way “Ms. Jackson” reinvented psychedelic soul as secular gospel and the breakup song as a simultaneous recrimination/apology, the player-as-dandy-as-freak layers to “So Fresh, So Clean.” But they went for the big-swinging art-funk statement so many different ways that they left countless possible directions open: were they lascivious womanizers (“We Luv Deez Hoez”) or perfect gentlemen (“I’ll Call Before I Come”), celebrants of opulent, violence-tinged danger (“Gangsta Shit”) or its most perceptive critics (“Red Velvet”), lost and uncertain about an unguaranteed future (“Spaghetti Junction”) or defiantly ready to conquer it on their own terms (“Humble Mumble”)? (The latter track features one of Andre 3000’s simplest yet deepest explanations of those multitudes: “She said she thought hip-hop was only guns and alcohol/I said “Oh hell naw!” but yet it’s that too.”) The trick was to make it feel like a unified if duality-borne perspective rather than a series of contradictory ideas, and it helps that more often than not their empathetic side spoke loudest. Think “Toilet Tisha” and its teen-pregnancy scenario, framed less as a moral scolding than a mournful attempt to reckon with a harsh reality, or the way even their angriest political invective in “Gasoline Dreams” acknowledges that you can’t just rail against the system without having real love for its victims. All that was left to do was to make the kind of music that did for funk-informed Southern bounce in 2000 what George Clinton did for doo-wop in 1970: an elaboration so intensely weird and prescient and formative in that prescient weirdness that it felt — and still feels — like someone had invented an entirely new kind of euphoric catharsis.