Apartheid became an official policy in South Africa following the victory of the National Party in the 1948 general elections, and its racist measures were consolidated and enforced over the following decades. The emergence of South African jazz and the pinnacle of its cultural and political significance coincided with this period of increasing violence and racial segregation, as cultural expressions became forms of protest and resistance. The story of township jazz is one that exemplifies the role that music can have in dismantling oppressive systems.

The urbanization process that started in the late 19th century following the Mineral Revolution resulted in a new, black proletarian melting pot that brought together Africans from various ethnicities and cultural backgrounds. The conditions in these rapidly expanding shanty towns were dire, and one of the few places people could find reprieve from their daily hardships were the shebeens, illicit bars that offered bootleg alcohol and a place where people could gather, play music, dance, and sing. Rhythms and melodies from different parts of South Africa mixed with the music of the Cape Malays, and instrumentation brought over by the white colonizers was thrown into the mix too. This new sound became known as marabi, which laid the groundwork for the development of styles such as mbaqanga and township jazz.

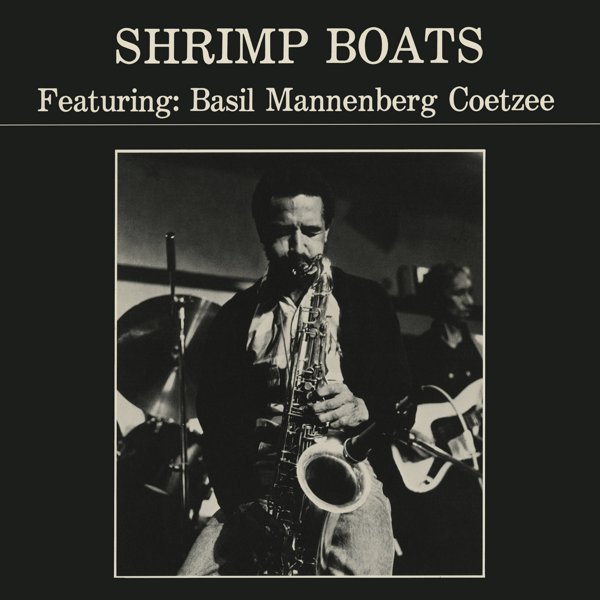

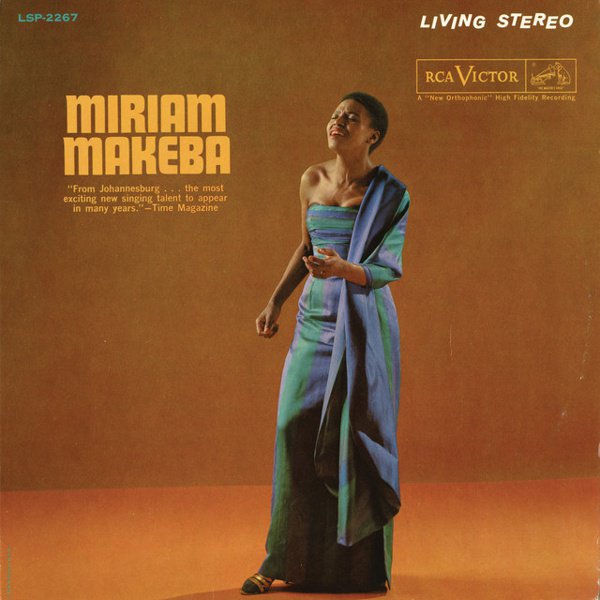

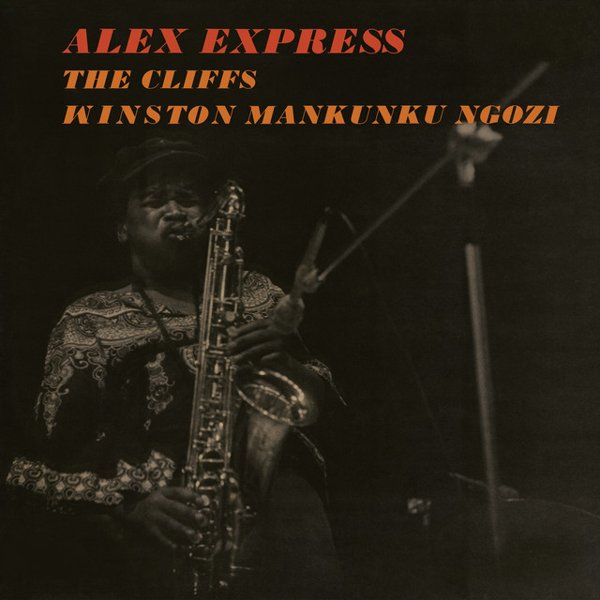

In the late 1940s and early 1950s Cuban and American jazz records started making their way to Africa, first through sailors from the other side of the Atlantic, and later through major labels who decided to open up the African market. While Cuban music quickly became the sound du jour in much of Central and Western Africa, in South Africa it was jazz that made an impact, with hard pop and free jazz quickly fusing with the already eclectic sound of township music. Township jazz was the sound of the new, non-tribal, urban black identity, and the apartheid regime was threatened by it. At the same time, white promoters tried to capitalize on its growing popularity, and there are many horrendous stories of black musicians being made to play behind screens while white “musicians” mimicked the notes onstage. Even famous musicians such as Miriam Makeba were exploited by white promoters and made to play for very little money and for all-white audiences.

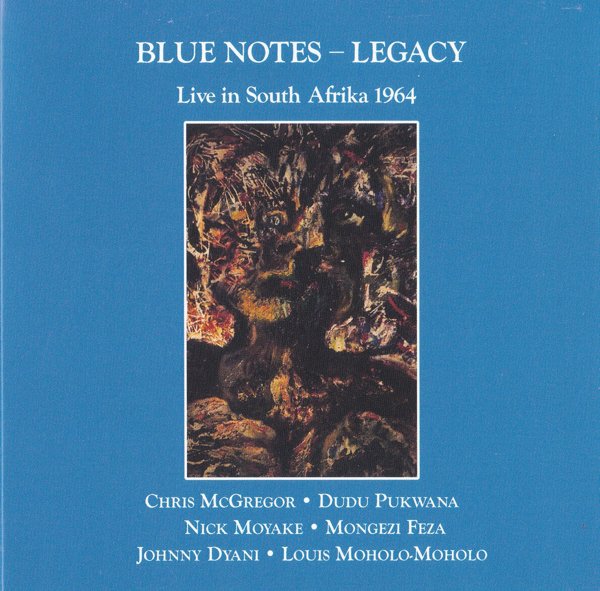

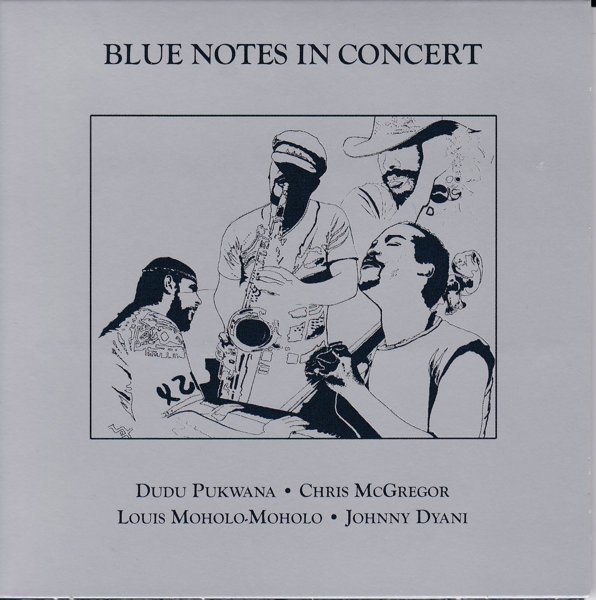

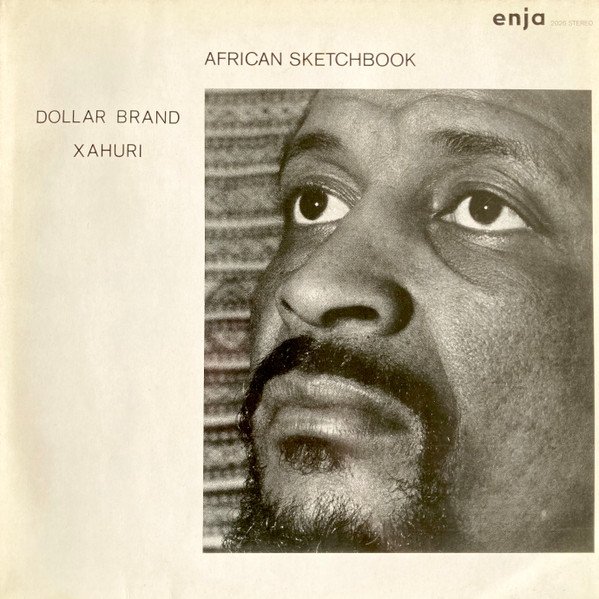

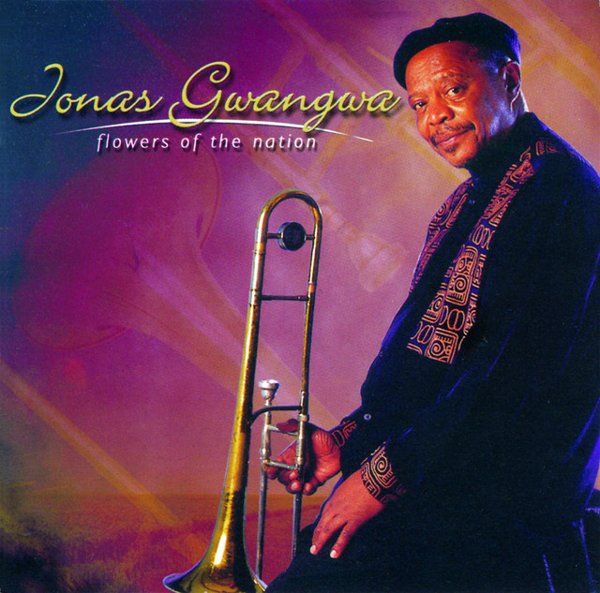

Censorship, curfew, oppressive labor conditions, and travel restrictions caused many of the pioneers of township jazz, such as Hugh Masekela, Miriam Makeba, Abdullah Ibrahim (aka Dollar Brand) and Jonas Gwangwa to leave South Africa and live in exile in Europe and America, where they also had a big impact on the jazz scene. But far from abandoning their cause, they had a major role in internationalizing the anti-apartheid movement and gaining support on a global scale.