The 90s blossoming of dance and electronic music saw a corresponding rise in artists using the techniques, sound palette and musical tropes of dance floor genres like house, techno or hip hop in new, non-dancefloor music like ambient, chill out, downtempo and trip hop.

Trip hop is something of a maligned 90s electronic music genre, to the point that many ‘classic’ trip hop artists reject the label entirely. And it’s kind of understandable; trip hop is a clever pun, but it doesn’t really adequately sum up the serene beauty of much of Massive Attack’s work, or the deep emotion contained within the lovingly trimmed samples in DJ Shadows’ Endtroducing…... And its reputation hasn’t been helped by the fact that since its birth — Mixmag journalist Andy Pemberton first coined the term in print in 1994 describing DJ Shadow’s In/Flux single — there have been plenty of landfill-quality trip hop releases. However, there are also many musical gems that broadly fall into the genre, particularly from its first early/mid-90s flowering, albums that cleverly drew together a number of related, and disparate musical elements to craft a fresh, immersive and influential sound.

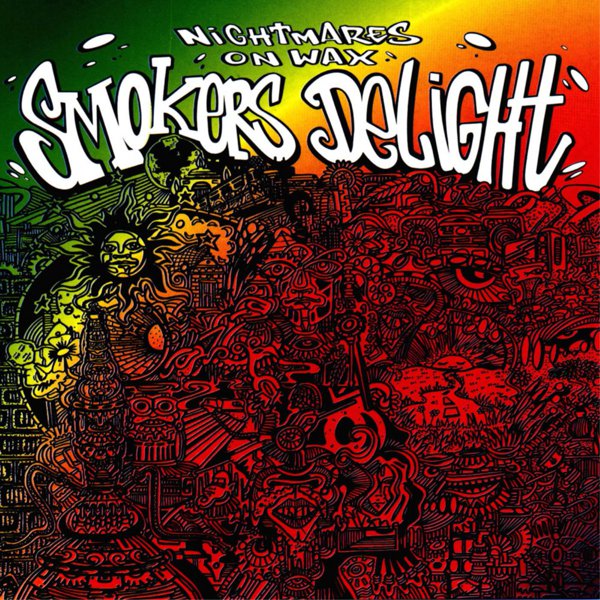

So it’s a journalist-created genre that was applied to some music retrospectively, but with that caveat in mind, were we to sum it up, trip hop is essentially instrumental hip hop, often with a psychedelic bent, variously incorporating elements of dub reggae, ambient, soul, funk, noir soundtracks, spy film/cop show themes and jazz. It’s a heady mix, one that generally explores an introspective, often unsettling aesthetic, with an oft-otherworldly sonic palette of bass, abstract atmospheres, mutant sampling and a focus on the emotional possibilities of texture and timbre. Languishing in sleepy tempos between 70 and 90 bpm, trip hop emerged, much like ambient, as a club-adjacent genre for after-club listening, a tripped-out, soporific audio balm to soothe clubbers returning from a night of the ‘mentalism’ of early 90s UK clubbing.

Obviously hip hop was the main genre parent, passing on the traits of sampling, scratching, a certain tempo range, and a particular rhythm — the boom bap beat, adapted and repurposed from 70s funk — but other musical DNA was involved too. The space, depth, pace and bass of dub reggae, were all crucial elements in the sound and feel of much trip hop. Trip hop shared ambient music’s non-dancefloor, psychedelic and experimental approach. And besides sampling 70s soul and funk in the hip hop tradition, lots of trip hop also drew from library music, nostalgic 60s TV themes and mod-ish film soundtracks, often producing a slightly queasy, out-of-time and unsettling feel to the genre.

There were trip hop antecedents — Double Dee & Steinski, Coldcut and Bomb The Bass for example all produced sample-based instrumental hip hop collage records in the late 80s — but bohemian-friendly UK city Bristol with its long-established reggae sound system culture was the birthplace, and Massive Attack’s debut album Blue Lines is the original. A smouldering, glowing gem in UK electronic music history that emerged from the city’s sound system and underground party scene, Blue Lines was released in April ’91 and became ingrained in a generation of clubbers’ psyches as it looped around on repeat, the soundtrack to countless post club sessions.

Blue Lines is a contradiction in the trip hop story though; whereas much trip hop that followed was largely instrumental, it featured beautifully delivered vocals, rapping, and premium quality songs. But much of what was pioneered on Blue Lines would become codified in many future trip hop releases: the funereal tempos, dub-derived sense of space, the same rhythmic bare bones used in hip hop, and the science of drum beat reconstitution and recycling. It also, in contrast to much of the party-friendly vibe and ‘wacky’ samples of outfits like Coldcut, pioneered a very different aesthetic. Defined by smoked-out, edgy, introspective raps to match the smoked-out, edgy, introspective soundscapes, Blue Lines exhibited a soft sensitivity to the fragility of the post-rave soldiers, mixed with the paranoia-tinged unearthly oddness of the comedown.

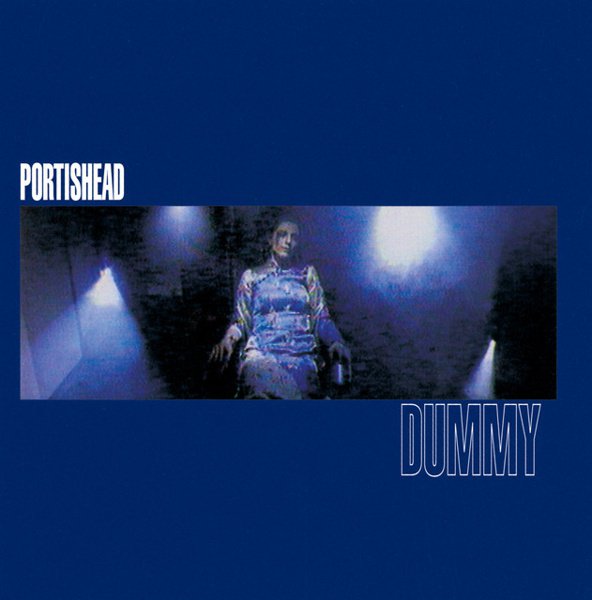

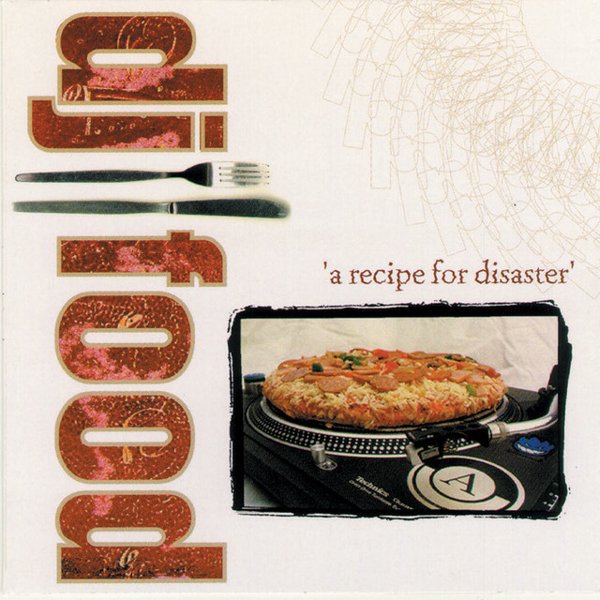

Different artists took the template in their own particular direction. Portishead released Dummy in August ’94 which went on to win the Mercury Music Prize the following year. It was a dark, cinematic, sombre opus, with home-made beats (they recorded new rhythms then treated them like samples, cutting them up, looping, re-editing them and running them through fx equipment to add a layer of audible studio grit and grime) the basis for their updated take on heartbreaking, bluesy torch songs. DJ Cam on the other hand produced a series of dreamy, uncomplicated, instrumental hip hop albums using a sample palette of jazz piano, horn, vibraphone and strings, while DJ Food pursued a more upbeat direction packed with brash beats, turntablism and rhythmic experimentation that went far beyond the original trip hop template.

DJ Food, along with artists including Funki Porcini, The Herbaliser and London Funk Allstars recorded on UK label Ninja Tune, whose mid-90s output was a gloriously eclectic collision of hip hop, dub, drum & bass, electronica and turntablism. Ninja, along with Mo Wax — home to DJ Shadow, La Funk Mob, Attica Blues, DJ Krush, U.N.K.L.E., and Palm Strings Productions — released much of the best mid-90s trip hop. Manchester’s Grand Central Records also put a series of lovingly crafted instrumental hip hop tracks in the mid-90s, less ‘trippy’ than say, the sonic experiments of Luke Vibert on Mo Wax, but beautifully put together, with pristinely produced rhythm tracks and a snare sound you could cut glass with. And French producers like La Funk Mob, Kid Loco and DJ Cam also created their own, respectively, minimal, lounge and jazzy takes on the genre.

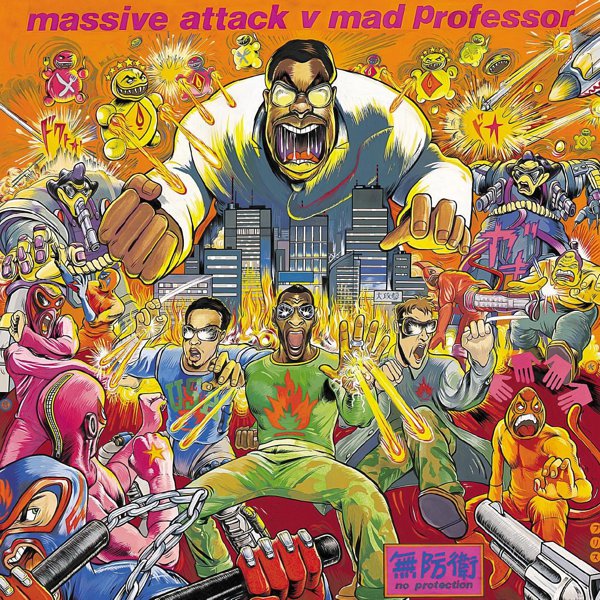

At its best, trip hop has produced some extraordinary albums; from DJ Shadow’s pioneering Endtroducing….., a haunting and emotive debut that truly demonstrated the possibilities of sample-based hip hop, to the cold, minimal, distilled goth-hop of DJ Krush’s Meiso, to the hushed, enigmatic, nocturnal light and shade of Massive Attack’s Protection, the genre with the bad name includes some truly beautiful music.