Detroit is the birthplace of techno and Chicago is the birthplace of house; but Detroit has also been making house music since before techno even had a name. It’s hardly surprising that Detroit house exists, given house and techno’s common musical ancestry, and that they developed at the same time in US cities around 300 miles apart via the same synths, samplers and drum machines. The pioneering mid/late 80s techno releases of ‘Belleville Three’ Juan Atkins, Kevin Sanderson and Derrick May, along with other Detroit producers like Eddie ‘Flashin’ Fowlkes, were some of the biggest selling tracks on the nascent Chicago house scene, and there were plenty of Chicago records from the time that would later be classified as techno too. (Quick caveat: many of the artists mentioned here make both house and techno, as well as various hybrids, some of them would probably dispute my categorisation of their music as one or the other genre, and some simply reject the genres completely; the space between what’s definitely techno and what’s definitely house will always remain something of a musical grey area and open to debate).

In their infancy the boundaries between the two genres were far from clear, with techno only really receiving its own distinct identity after the name of 1988’s genre-defining compilation Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit was changed from The House Sound of Detroit due to the last-minute inclusion of Juan Atkins’s “Techno City“. However, there were differences between the scenes that Chicago house and Detroit techno emerged from that affected their sound and character, and this was also reflected in Detroit house as it developed.

While there were exceptions, Chicago house was a largely gay scene whereas Detroit techno was generally straight. Chicago house had more songs while techno, except for Inner City and a few other acts, was generally instrumental. House was happy to reuse disco bass lines, recycle old disco vocals, and re-edit disco tunes. Techno meanwhile was more forward-looking and less enamoured of old-style disco. It was instead entranced by the musical possibilities hinted at by the various disco upgrades of new wave, synthpop and Italo disco that were the soundtrack of early 80s Detroit parties and clubs.

Writer Dan Sicko in his excellent Techno Rebels book spoke of a generation of Detroit kids who wanted to escape their city’s musical history of Motown and George Clinton and so turned to European new wave and synthpop, not realising they were just turning to another white interpretation of black music. “It was inevitable,” he observed, “with all that post-urban introspection, sci-fi images and affection for stark European synthesisers that Detroit’s music would end up someplace different to that made by the party kids of Chicago.” Those party kids inhabited a club scene that was, according to authors/DJs Bill Brewster and Frank Tope’s seminal Last Night A DJ Saved My Life, full of “big, fired-up clubs, all those kids frantically making records, hanging out, biting ideas off each other.” In contrast, techno was incubated in the quiet suburbs of post-industrial Detroit, and the character of the two cities clearly had an influence, as described in Last Night…: “The two styles were very different emotionally too, in keeping with the cities that bred them: while house was about lustful churchy energy, techno deals in lament and anxiety.”

Inevitably many of the influences that drove the style, approach and sound of techno also influenced the house music that came out of Detroit at the same time. Perhaps the stylistic differences aren’t immediately apparent, but fans will tell you that Detroit house has its own distinctive character. Certainly initially, Detroit house music wore its disco heritage quietly, eschewing its diva vocals and camp energy in favour of outré chord stabs, stately synthetic pads and sci fi synth work. Early/mid-90s Detroit house like the pounding, efficient, shimmering, abstract grooves of K-Hand, the clear, crystalline, functional-funk of Mike Huckaby, or Octave One’s occasional forays into emotive, uplifting deep house were often a little more futuristic and spacey than their euphoric, sweaty Chicago counterparts and often felt a little more measured, restrained and controlled too.

Sibling producer duo (sometimes trio) Octave One’s classic second-wave techno EP Day By Day from ’92 features a couple of great examples of the early Detroit house sound in “Jackie’s Theme” and “In The Breeze.” The piano riffs, the Moog-sounding bass lines and the synth washes are all very similar to contemporaneous Chicago house but the drums sound different; Detroit house drums often had less swing and ‘jack’ than Chicago house and sometimes came with a more rolling, relentless, production-line style rhythm. There tended to be less sampling and more programmed elements than Chicago house tracks too, making for a more futuristic aesthetic. And Detroit house, much like techno, was not as obviously joyous or excited as Chicago, with some kind of restraint and reserve in the chords and melodies, a sense of introspection and melancholy, and perhaps even a flavour of that famed Detroit post-industrial-malaise that was so vital in defining techno’s character.

Octave One were one of several artists given a kickstart by inclusion on the Equinox compilation on Carl Craig and Daniel Booker’s Retroactive label. Craig would go on to be one of Detroit’s most influential and idiosyncratic electronic artists, his productions and labels often redefining and broadening the sonic possibilities of both house and techno. Retroactive only ran for a year in 1990 but as Sicko in Techno Rebels says, it was “…a preview of the next two years of Detroit techno — a subtle declaration that its sound could no longer be defined simply by the productions of Atkins, May and Saunderson.” Amid the compilation’s second-wave-defining techno was a pair of beautiful, dreamy deep house tunes, Urban Tribe’s “Covert Action” and Craig’s “As Time Goes By (Sitting Under A Tree)” featuring Sarah Gregory, along with a very housey tune, “The Theory,” from techno militants Underground Resistance.

Although best known for hard-hitting purist techno, Underground Resistance also recorded some very-house material during this period too. Their 1990 “Your Time Is Up” with vocalist Yolanda came with a distinctly Italian house-sounding mix, and the hissing 707 disco hats, chunky Moog-ish bass and smooth keys of their “303 Sunset” sound very Chicago house while maintaining that Detroit cool, detached, serene aesthetic that techno had perfected.

Octave One’s 430 East label, established in 1990, mainly released techno but also put out fellow Detroit-er Terrance Parker’s first EP in ’92. Parker would go on to be another influential figure in Detroit house, pursuing his own strand of devotional, gospel piano house to substantial impact and success.

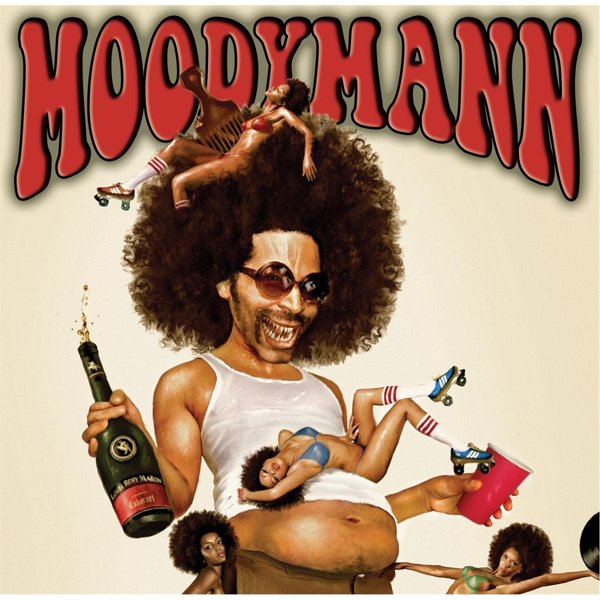

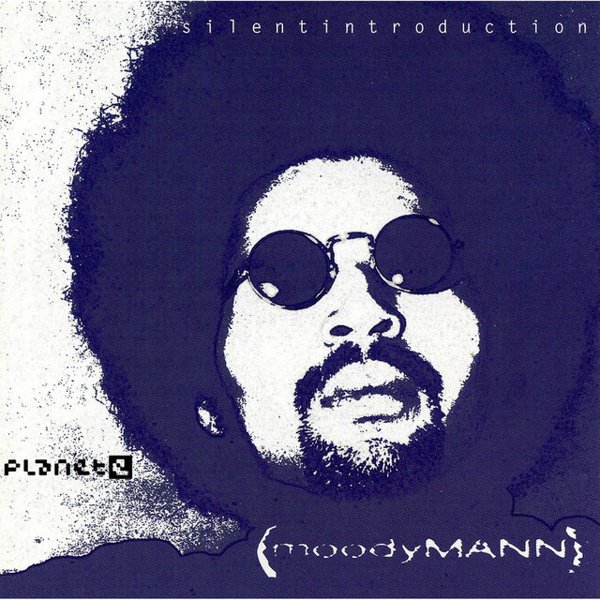

After Retroactive folded, Craig established his Planet E label in 1992, home to mostly forward-thinking techno but that also put out a pair of brilliant and influential Detroit house albums, Recloose’s Cardiology from 2002 and Moodyman’s Silent Introduction from 1997. Moodyman was one of several Detroit producers who in the mid-90s re-embraced disco but in a distinctly Detroit way: playing down its celebratory and euphoric nature and distilling it down into relentless, looping, psychedelic grooves. Moodymann launched his KDJ label in ’94 and, with occasional select releases from the likes of Andrés, Alton Miller and Rick Wilhite, for twenty years turned out a catalogue of raw, rolling, disco/R’n’B-sample house: hypnotic, hazy, occasionally out-there but always dance floor ready. Chicago house producers at the time like Glenn Underground, Gene Farris or DJ Sneak tended to use their disco samples to generate excitement and euphoria, rinsing out the most uplifting orchestrated two-bar sample loops and placing them on a bed of skippy, highly swung garage-house beats. The mid/late 90s Detroit house of artists like Moodymann, Andrés and Rick Wilhite took a different approach to the drums, often using crackly old vinyl drum loops and chunky hip hop-tinged MPC beats alongside Roland drum machines, and they worked disco and R’n’B elements into a new, narcotic, gauzy, twisted and space-age version of deep house, futurist and detached, like its older brother techno.

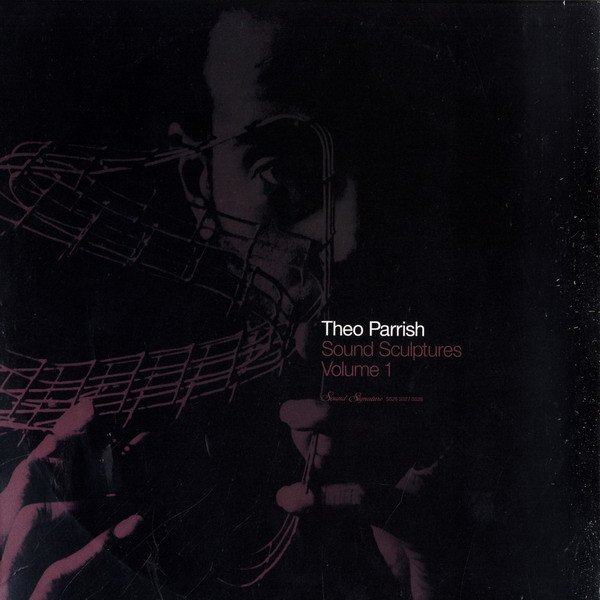

This strand of Detroit house was part of a clear broadening of the sound in the second half of the ‘90s that also included the sonic experimentalism of Theo Parrish, a Detroit producer and DJ who launched his influential Sound Signature label in ’97. In different ways both Parrish and Craig were key in redefining what house music could be, widening the possibilities through experimentation, and often transcending genre entirely. In 1998 Parrish, along with Moodymann and Rick Wilhite launched Three Chairs, a Detroit deep house label for their collaborative Three Chairs project (Marcellus Pittman joined in 2003), re-tooling ancient disco and soul into new, hypnotic shapes, continuing the Detroit tradition of integrating jazz and electronic music, and again, pushing the boundaries of what house could sound like.

2002’s Detroit Beatdown Vol 1 compilation, put together by Detroit producer and DJ Norm Talley, was a great audio snapshot of the more introspective and laid-back side of Detroit house at the start of the 2000s: Malik Alston’s “Butterfly” was a delicate, light-touch melding of soul-jazz and deep house, Rick Wilhite’s “Ruby Nights” delivered that languid, twisted, intense Detroit narco-house sound, Theo Parrish’s “Falling Up” was a skeletal dissection of house and jazz rhythms, and the album introduced the slick, space-age deep grooves of Delano Smith, Mike ‘Agent X’ Clark’s nocturnal disco-chuggers and Pirahnahead’s sparse, electro-tinged house.

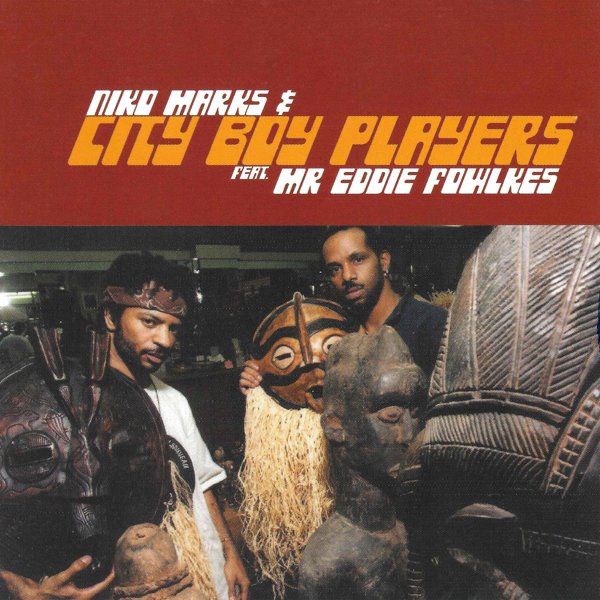

In 2012 Marcellus Pittman collected together his first few vinyl releases on his Pieces album, the conflicting cross rhythms and technical/production wizardry on show demonstrating just how far Detroit house had moved on from the warm fluffy pad chords, Rhodes keys flourishes and 909 beats house music template. Through all its various stylistic mutations and hybridising, genre divisions and sub-divisions — the crisp, space age, raw grooves of Rick Wade, K-Hand and Mike Huckaby, the potent, hazy, smoked-out, sampleology of Moodyman or Rick Wilhite, the angular, fragile, loose and unconventional rhythms of Theo Parrish, Three Chairs’ psychedelic discoid jazz house, or the secular devotional piano anthems of Terrance Parker — the Detroit house community has produced a rich, potent and influential catalogue that has continued to be further developed by new generations of artists. Detroit producer Patrice Scott’s Sistrum label has been putting out smokey late-night house cuts since the mid-2000s, including music from seminal players like Alton Miller and new school Detroit producers like Javonntte, whose current 12” releases continue to fly the flag for sophisticated, forward-facing instrumental Detroit deep house. Producer, songwriter and DJ O B Ignitt’s Obonit label put out a small but perfectly formed discography of silky deep house and understated techno between 2014 and 18. Detroit singer, producer and keyboardist Niko Marks remains a remarkably prolific house and techno producer, clocking up around 50 albums in 25 years, his latest mini-album Jazz Nagas another bumper package of quality dance floor house music. Kyle Hall’s Forget The Clock label has been slowly crafting a refined catalogue of funk-filled, sophisticated deep house since 2019, while Rick Wade’s career may have started in ‘94 but he’s still putting out relevant, cutting-edge house music on quality labels today.

The Detroit house spectrum in the 21st century includes music that has moved far away from the standard 4/4 kick/hats/snare basics, where ill-quantised beats fall apart and reassemble themselves, where off-key samples create queasy, hallucinatory house, and where sound design, found sound and sonic experimentation push the boundaries of what house can be. But it also includes the highly orchestrated and pristinely arranged accessible soulful house of Alton Miller, those mesmerising tripped-out disco-narco grooves of Moodymann, the club-ready raw ’n’ real deep house of Norm Talley, the sensuous sci-fi tech soul of Marcellus Pittman, and much more. From a city that has given the world so many musical innovations, Detroit house music in the 21st century is quietly, with class, restraint, and undeniable groove, continuing to deliver.