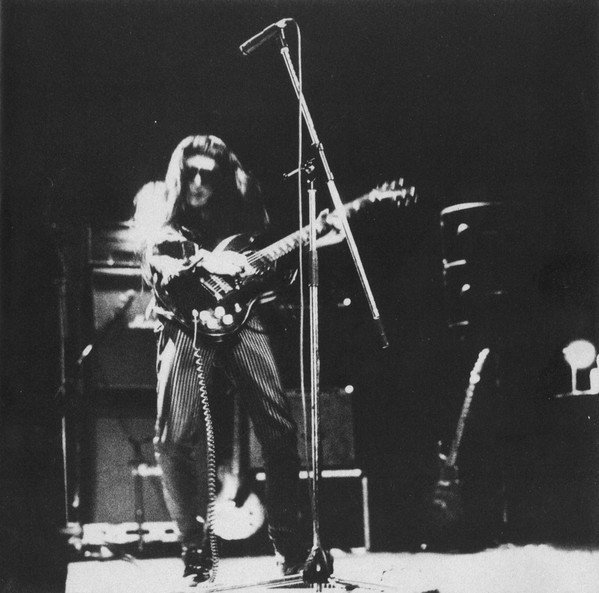

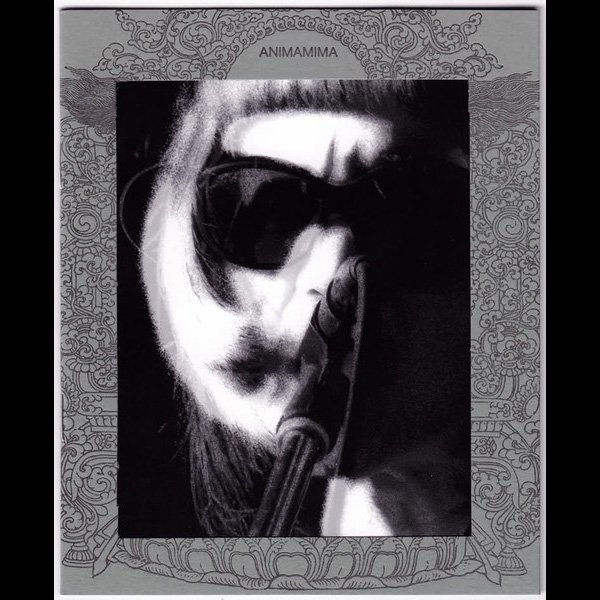

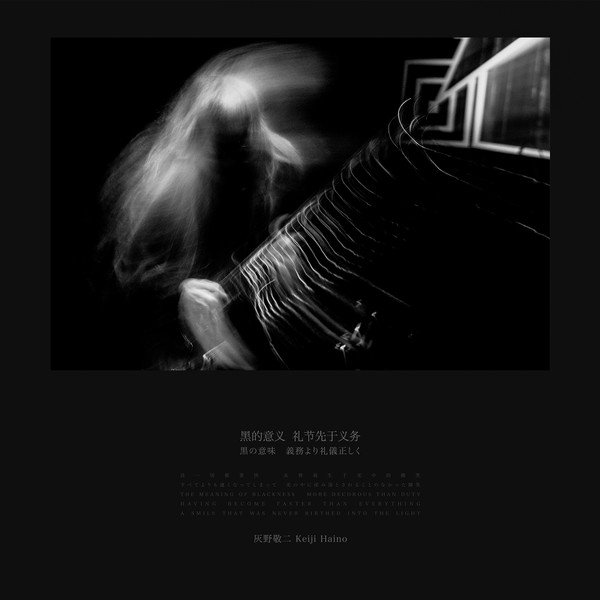

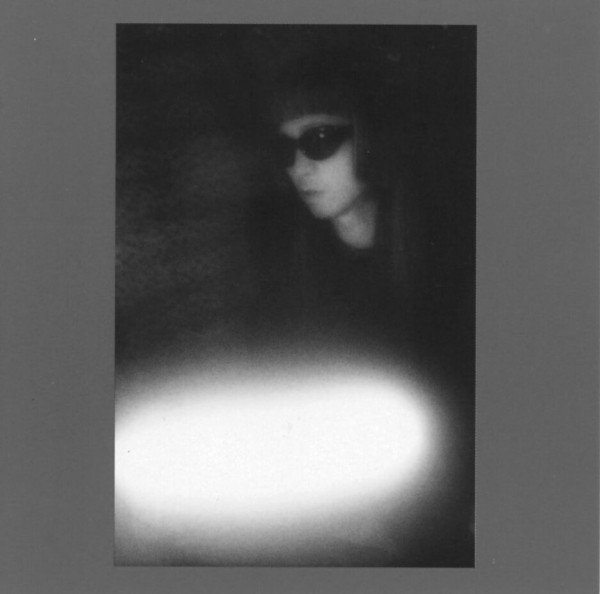

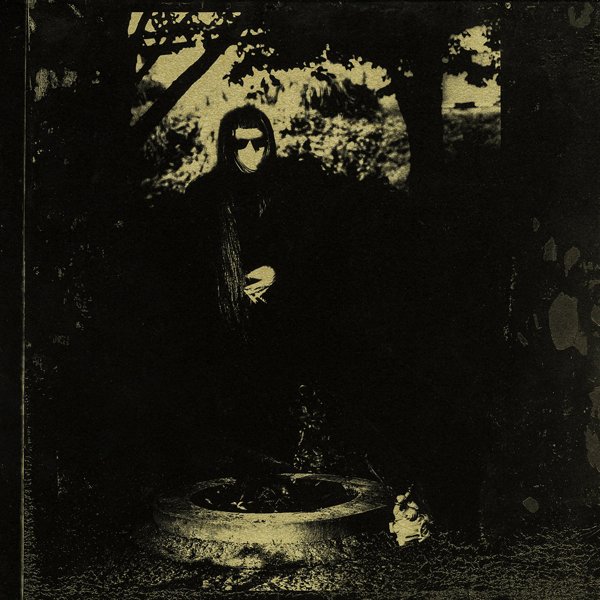

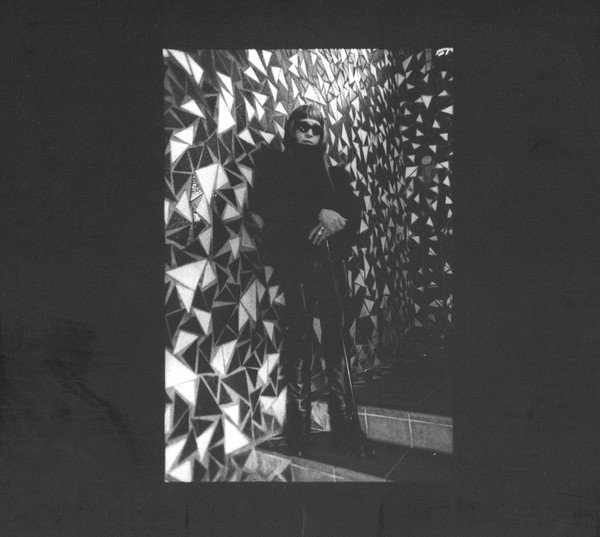

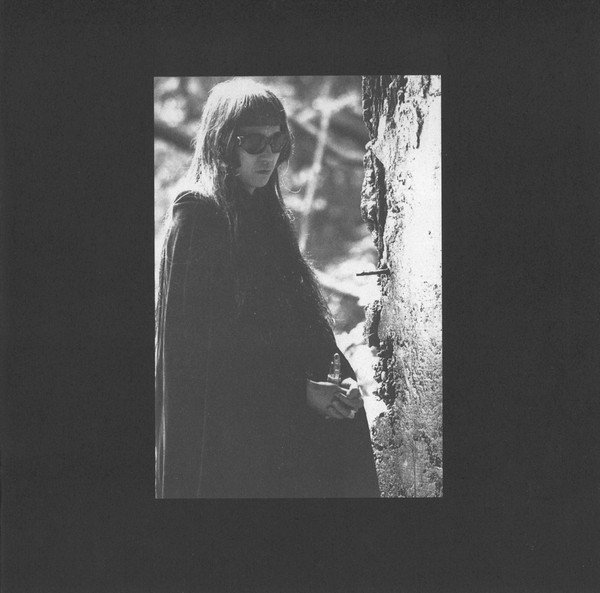

Keiji Haino has never been seen in public without gigantic, Miles-Davis-in-1969 sunglasses. He has never been seen in public in clothes that are not rigorously formal, beautifully tailored, and black from head to toe. He has never been seen in public in sneakers. He has never been seen in public with his waist-length hair (once a glossy black, now a shimmering gray-white) in a ponytail. When he enters a room, he brings the darkness with him, and the ambient volume seems to drop by five decibels. He is Keiji Haino, 100%, always.

Although Haino’s been making music in his native Japan since the early 1970s, solo and with the group Lost Aaraaff, he really “emerged” as a key figure in the global avant-rock underground in the early 1990s, when a flood of releases began, mostly on the PSF label with a few titles showing up on other imprints. He immediately gained a reputation as an almost shamanic performer, his vocals alternating between a mournful croon and a harsh, choked-off shriek and his guitar delivering bursts of shearing postpunk noise and floods of distortion that fill the room like storm clouds. I saw him live for the first time at CBGB, performing a solo guitar piece at eyeball-vibrating volume that gradually transformed into a duo with saxophonist John Zorn, neither man giving an inch as they attempted to blast the tiny club’s walls down.

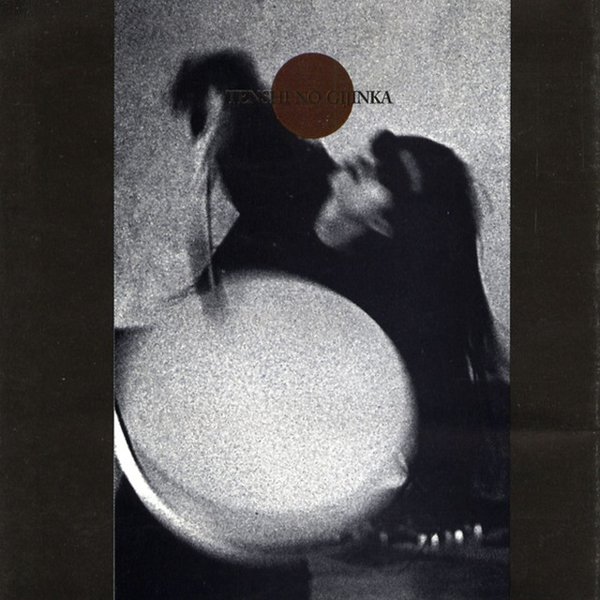

His work is never pure noise in the Merzbow-ian sense, though. There is always a calm at the center of the storm, and a slowly building, almost ceremonial structure to his performances, whether he’s playing just electric guitar or hurdy-gurdy (a stringed instrument operated by turning a crank) or synthesizer, or switching between them over the course of several hours. He will transition suddenly from extremely loud assaults to passages of almost suspenseful silence, and often works with drones, filling the room with rising swells of sound until it seems like even he can’t take the pressure, and he begins to chant and wail. After the fact, pieces will be given long, poetic titles like “If A Billion Curses Already Exist, You Should Draw Out The Billion And First Prayer” or “(Not At All Wanting To) But Has Become” or “Staring At A Point In Time Memorizing. Vowing Never To Return.” Watching one of his performances, it’s easy to find yourself holding your breath, and even some of his CDs, particularly the most overtly ritualistic ones like the all-percussion Tenshi No Gijinka or the electronic Abandon All Words At A Stroke, So That Prayer Can Come Spilling Out can have that effect, a remarkable demonstration of his work’s almost elemental power.

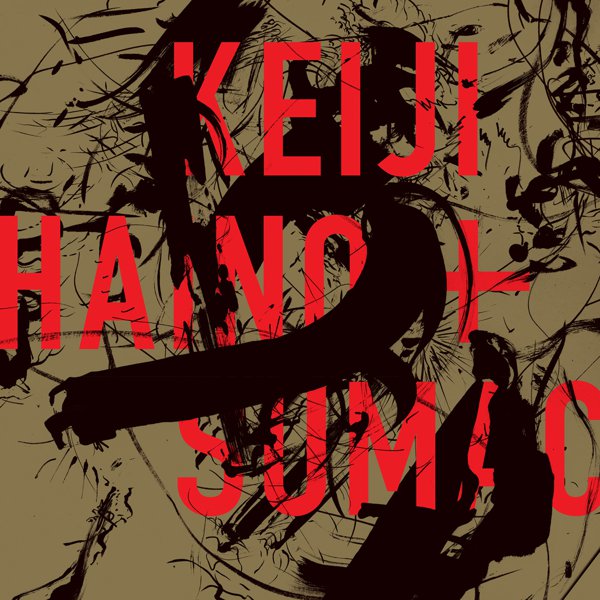

Haino has always been open to collaborations with a vast range of creative partners, from heavy rock acts like Boris and Musica Transonic, where he riffs in an almost metallic fashion, to European improvisers like Derek Bailey and Peter Brötzmann to Jim O’Rourke, Stephen O’Malley of Sunn O))), and even the Finnish electronic music crew Pan Sonic. He’s also expanded his instrumental palette over the years, developing an interest in solo percussion rituals (cymbals, gongs, tambourines, etc.), then becoming fascinated by the hurdy-gurdy. He’s recorded and performed on synthesizers, drums (electronic and traditional), harmonica, flute, saxophone, and sometimes his voice alone. He approaches every situation with the same intensity, always living in the moment as an improviser but treating each encounter as a chance to explore the darkness that is his chosen territory.

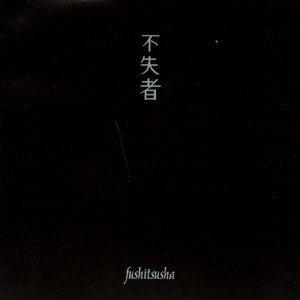

By far his most famous project is his long-running group Fushitsusha, a psychedelic power trio that’s as heavy as any doom metal band but as free as any improvising unit. The classic lineup, with bassist Yasushi Ozawa and drummer Jun Kosugi, were a remarkably attuned unit, Ozawa often serving as a co-lead instrumental voice as Haino’s guitar created vast fields of scorching noise and Kosugi slammed the drums with militaristic fervor while completely ignoring any conventional sense of time. Their 1991 double live CD, sometimes referred to as Live II but also as a self-titled or untitled release, is one of the key documents not just of his work but of 1990s Japanese psychedelic rock in general. Other live albums, like Gold Blood, I Saw It! That Which Before I Could Only Sense…, and Purple Trap, are less universally lauded but every bit as powerful. Somehow, in 1997, Haino jumped from PSF to the Japanese major label Tokuma, and released four stunning studio discs with Fushitsusha — A Death Never To Be Complete, The Time Is Nigh, A Little Longer Thus, and The Wisdom Prepared, the last of which consisted of a single 76-minute track. (He also put out two solo albums, one featuring guitar and the other hurdy-gurdy, on Tokuma.)

Haino’s discography is vast at this point; the albums reviewed below barely scratch the surface of his body of work. But they give a good idea of its scope, while also revealing the thick black through-lines that unify all of it. And he continues to record and perform, bringing a little bit of darkness with him wherever he goes and somehow making the invitation to join him there impossible to resist.