Erik Satie remains as confusing a figure in the history of classical music as he was in his day. The French composer, born in 1866, received his music education at the prestigious Conservatoire de Paris, but was considered an unremarkable student due to his sparse playing style and unconventional way of writing musical notation, often neglecting to use bar lines or note time signatures. (He was called the laziest student at the school by one of his instructors, and was even expelled for underperforming in 1882.) His contemporaries, however, saw potential in him. He found kindred spirits in fellow Conservatoire pupils Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, who appreciated his experimental spirit and drew influence from his style as they went on to become leading figures in musical Impressionism.

Satie composed his first piece while furloughed from his studies, and signed his name as “Erik” for the first time. (His birth name is Eric; it’s unknown why he decided to alter the spelling.) From then on, he would reinvent himself again and again throughout the course of his life, pushing his music further toward the avant-garde with each successive transformation. He briefly rejoined the Conservatoire in 1885, becoming more obsessed with gothic architecture and Gregorian chant than applying himself. He wrote his Ogives (1886) during this time, but soon thereafter departed again to become the resident pianist at a cabaret.

He enjoyed an untethered lifestyle there, free from the rigidity of academia and imperious professors, and recorded his most famous pieces around this time – the Gymnopédies (1888) and the Gnossiennes (1889, 1890). After that, he founded his own church; he was the only member. In 1893, he started and saw the end of his only relationship. (During this five-month stint, he composed the Danses gothiques as a way to keep himself emotionally grounded.) The despair this episode brought upon him spurred another change. His way of coping was to assume the persona of “the Velvet Gentleman,” replacing his wardrobe with seven identical tan suits. He was never recognizable as the same man for too long.

Satie’s accomplishments eventually gained him respect within the institutions of classical music, but what makes his legacy endure is how much influence he would exert outside of it. His Furniture music (1917) series, which were meant to be played in various locales and not actively listened to, ostensibly invented the concept of ambient music. The ideas he conceptualized would echo decades beyond his death in 1925, being turned on their head by avant-garde minimalist John Cage in the ’50s and ’60s. With Satie in mind, Cage developed his theory that the space between the notes written on the sheet music are equally part of the performance, contextualizing ambient sound as essential to any musical experience rather than something to be tuned out.

In the following decade and on the other side of the world, Japan experienced an explosion of interest in Satie’s work that would be dubbed the “quiet boom.” Kuniharu Akiyama, an associate of Cage and an early participant in the Fluxus art movement, programmed a series of shows in Tokyo called the Complete Works of Erik Satie. This started a firestorm of Satie-related events across Japan, many of them multidisciplinary events that incorporated his music into works of cinema, dance, theater, and, of course, performances in communal spaces just like the Furniture music pieces. Notable disciples of Satie in Japan included Satoshi Ashikawa and Hiroshi Yoshimura, the fathers of kankyō ongaku (environmental music).

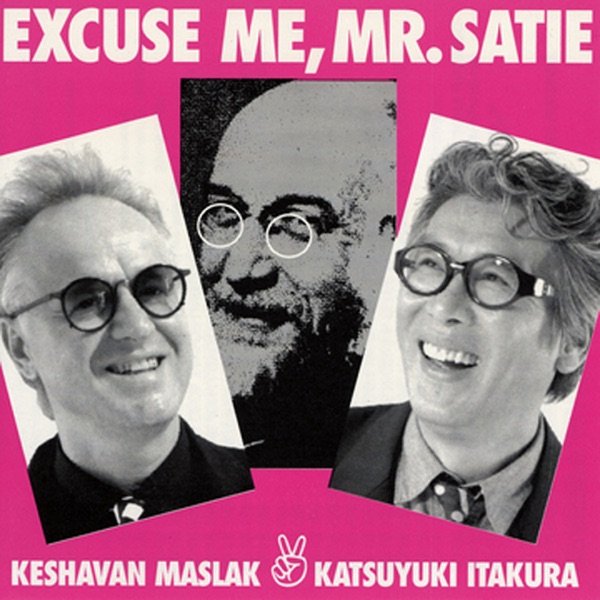

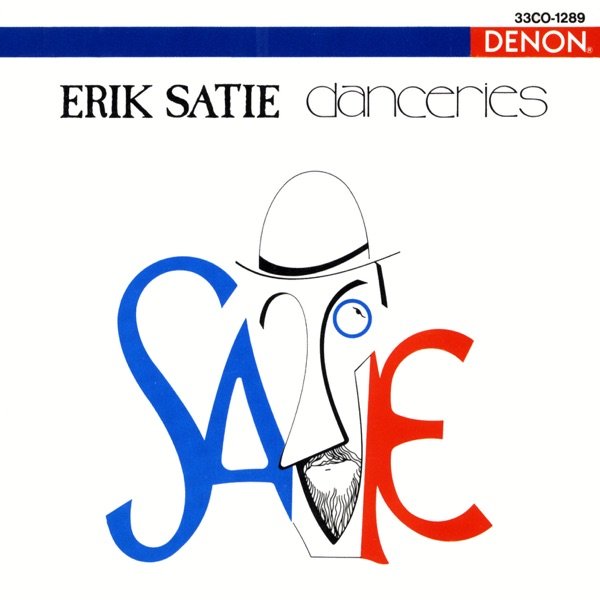

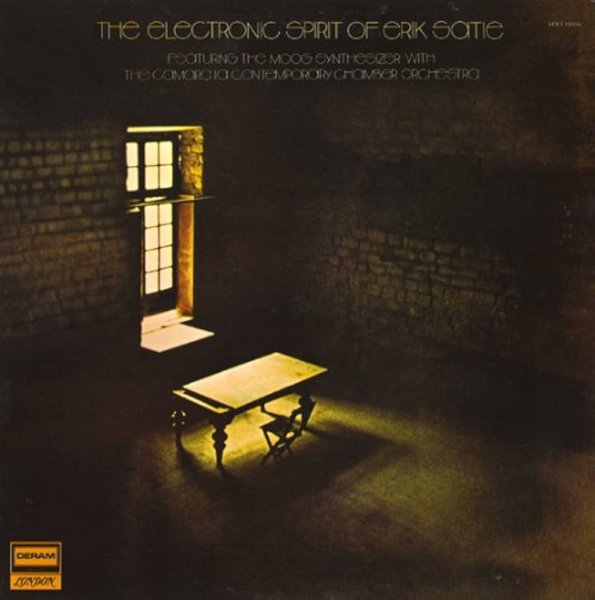

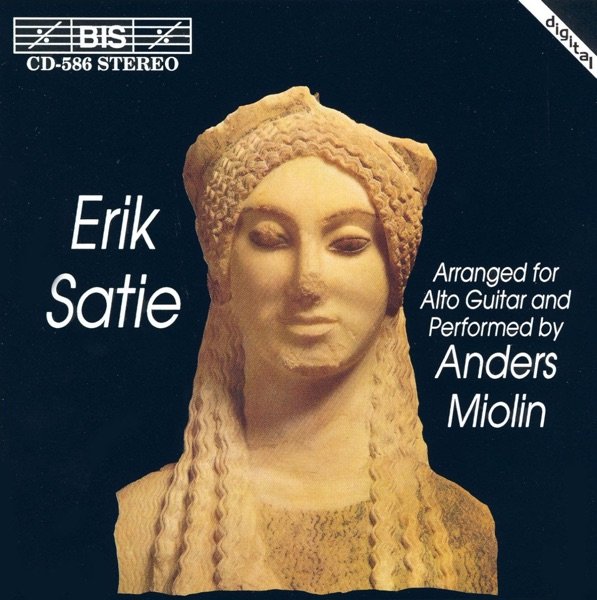

Today, Satie continues to be evaluated in different contexts and across every imaginable genre. Jazz greats like Mal Waldron have done Satie suites in a post-bop style, and even leftfield folk musicians have embraced the Velvet Gentleman. There are countless recordings of trained musicians tackling Satie with the utmost seriousness, but there are just as many weird and wild experiments. Here are twelve examples of musicians thinking about Satie outside the box.

![記憶の海 [The Other World of Erik Satie] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/記憶の海--The-Other-World-of-Erik-Satie-_600.jpg)