San Francisco in the ’60s, New York in the ’70s, Detroit and D.C. in the ’80s — if any other recent American music scene deserves to be mentioned in that storied company, it’s Chicago in the 1990s. It’s hard to think of another time and place where such a fertile musical subculture flourished, in which so many different personalities and aesthetics swirled together in such a natural and uncalculated way. What produced this climate was a rare convergence of talent: jazz trailblazers, rock radicals and genre-transcending conceptualists, all colliding and commingling, sharpening existing sounds and birthing entirely new ones.

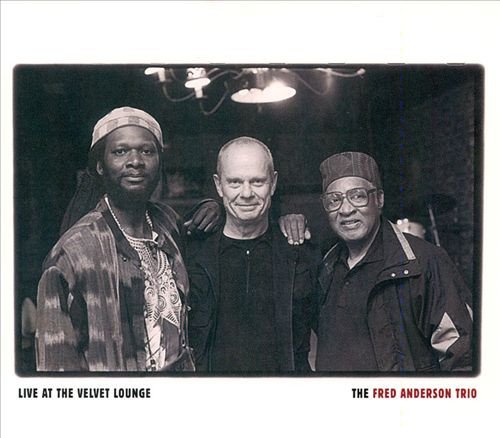

The story of Chicago in the ’90s — or, more broadly, the tradition of a radical Midwestern musical underground, period — starts with the AACM. The Black avant-garde centered around that collective, the Association of the Advancement of Creative Musicians, which had helped put Chicago on the map in the mid-’60s as a jazz and experimental-music hotbed, still held firm in town a quarter century on, bolstered by longtime members including Kahil El’Zabar and Edward Wilkerson Jr. and still-vital hometown hero Fred Anderson.

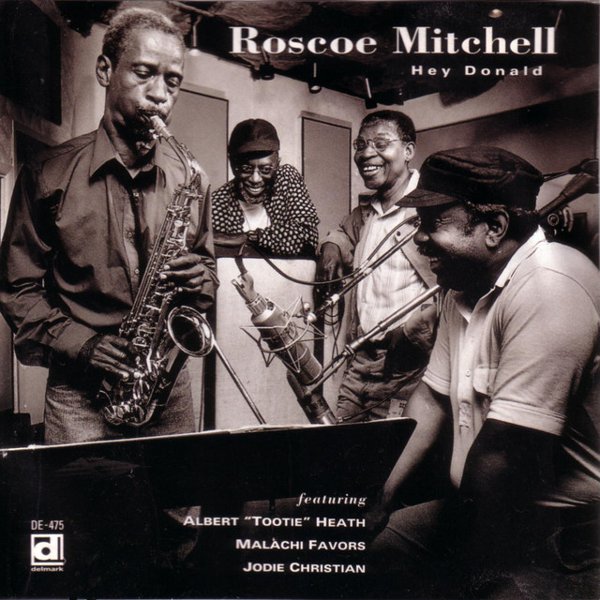

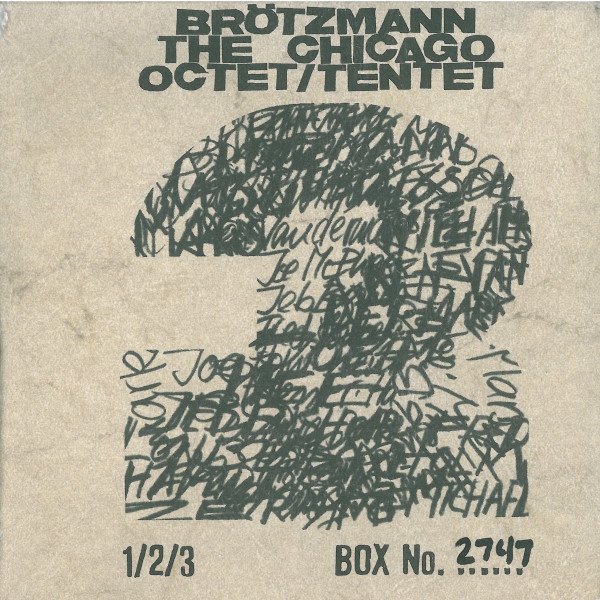

Meanwhile, a new jazz wave was taking hold, spearheaded by figures like Ken Vandermark, Mars Williams and the Chicago Underground union of Rob Mazurek and Chad Taylor, as well as the influential writer, producer and curator John Corbett, who began bringing key European musicians like Peter Brötzmann and Peter Kowald to town, fostering new collaborations and projects such as Brötzmann’s mighty Chicago Tentet.

At the same time, the local post-hardcore underground was booming, spurred on by the indefatigable Steve Albini, who was busy documenting the brilliance of raucous local punk-descended outfits like the Jesus Lizard while also launching his own essential new power trio, Shellac. Elsewhere in the scene, eccentric visionaries such as Jim O’Rourke and Thymme Jones were pushing the boundaries of song form and avant-garde sound assemblage in Gastr del Sol and Cheer-Accident, respectively, while U.S. Maple were cultivating a bizarre new musical language that seemed to stand apart from even the most peculiar guitar-bass-drums-vocals experiments of the past.

Another crew of post-hardcore veterans, including Bastro’s John McEntire and Slint’s Dave Pajo, were busy mining various musical zones, from dub to krautrock, and concocting a new hybrid sound that would come to be known as post-rock, yielding beloved projects including Tortoise and the Sea and Cake.

Crucially, none of these aforementioned scenes was walled off from the other, as avant-jazzers like Jeb Bishop could be found guesting on albums by Cheer-Accident and Gastr del Sol, Ken Vandermark could be heard jamming with Jesus Lizard guitarist Duane Denison in DK3, and older Chicago jazz heroes like Anderson could frequently be spotted onstage alongside their younger counterparts. And fortunately, vital labels including Thrill Jockey, Delmark, Touch and Go, Drag City, Skin Graft and Okka Disk were there to document it all.

This rundown only scratches the surface of a remarkable creative outpouring that’s still resonating today through the continued vitality of artists from this sprawling scene including O’Rourke, Vandermark, El’Zabar, Jones, guitarist Jeff Parker (a member of Tortoise and Isotope 217 and a frequent Chicago Underground collaborator) and even the newly resurgent Jesus Lizard. So step into our Windy City time machine, and make sure to bundle up.