Few developments sounded as open-endedly you can just do whatever thrilling as the cross-pollination of ideas surging through popular music in the mid-late ’90s. Hip-hop had not only begun to dominate pop, but had absorbed it to the point that it became one of the primary modes to engage with other genres — a prehistory of Clyde Stubblefield drum breaks and Bernie Worrell synths modulated into a futurist roots music that could underpin hardcore rap, smooth R&B, TRL-ready pop, and every permutation of techno and house that exploded into clubland during the decade.

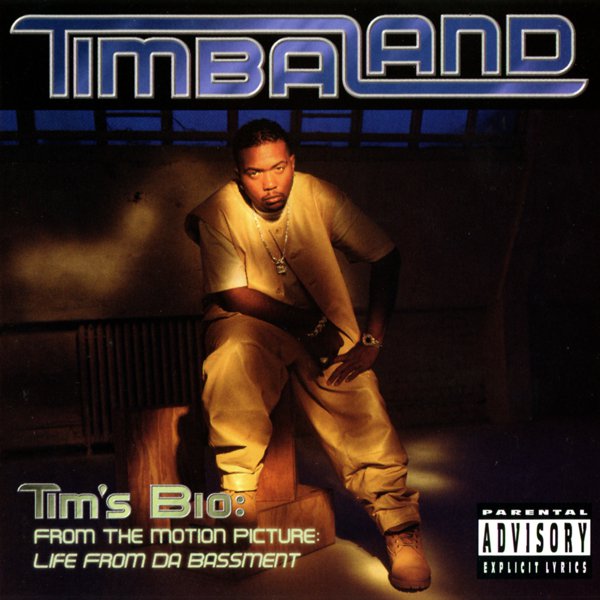

This made an artist like Timbaland inevitable, and yet sometimes inevitabilities can still shock the hell out of you. From the perspective of a quarter-century-plus after his first big production gigs, it still seems like an inexplicable fluke of popular culture that his music only sounds “of its time” due to association; next to even the most macrosonic Max Martin and Dr. Dre smashes he shared chart space with, his idiosyncrasies overwhelm any memories of what the era actually felt like. Tim’s sound was rooted in a malleable, often experimental-feeling sense of being able to get away with all kinds of supposedly-unwieldy notions of extramusical melodic accents — birds, crickets, babies — and outlandish synth tones that turned the developments of ’80s boogie funk and ’90s club jams into hilarious noise. The easy to hear / hard to replicate trick was to make the stuttering bounce of his unpredictable yet supremely catchy rhythms so undeniably propulsive that every additional element picked up along the way made it all sound both bigger and more capable of overpowering momentum, like some kind of musical Katamari. That approach led to one of the most omnipresent sounds of the mid-late ’90s, and it’d stay that way for at least another decade. But unlike many of his groove-minded precedents in R&B/dance/pop crossover — Giorgio Moroder, Chic, Jam/Lewis, Teddy Riley — Timbaland’s style never spawned obvious market-flooding imitators, despite its polygenre versatility. The only artist who ever really had a chance to foist mediocre Timbaland-type beats on us was late-career Timbaland.

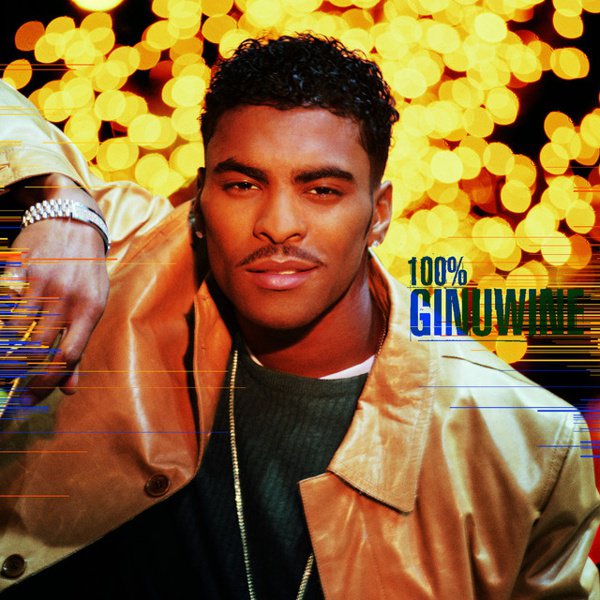

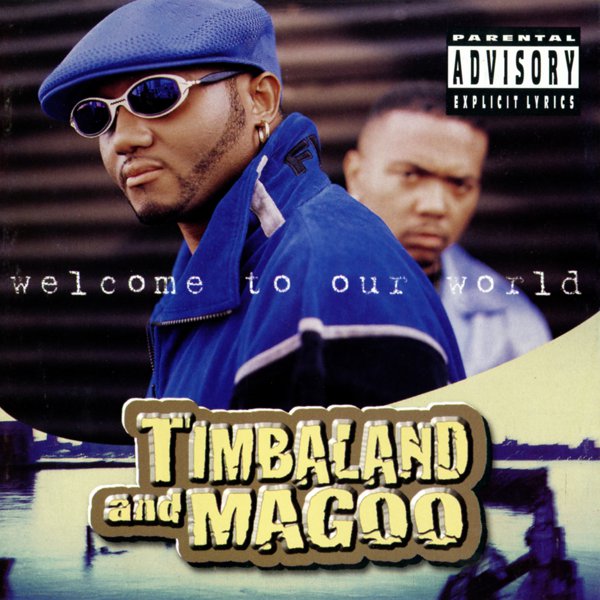

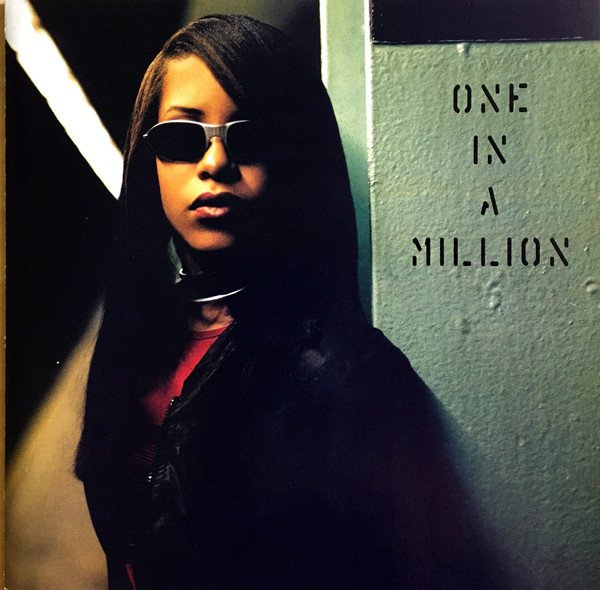

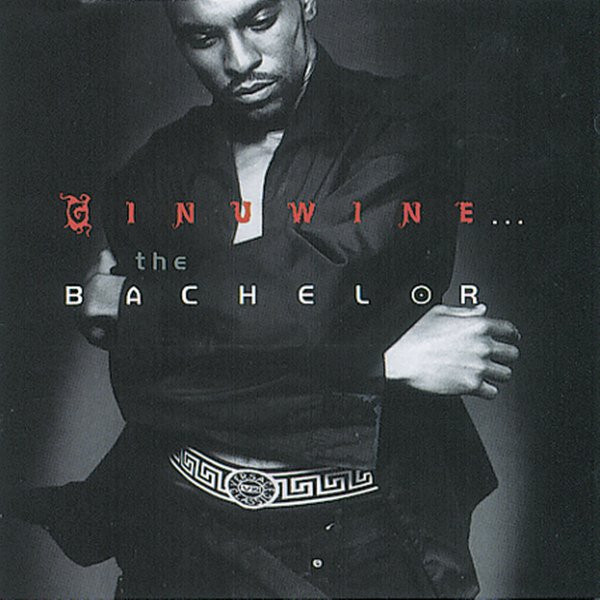

Like fellow Virginian era-defining producer Pharrell Williams — who was not only a teen-years musical collaborator, but his actual cousin — Timothy Mosley started out learning the rules of chart-busting R&B alongside an established mentor before he could rewrite them. After teaming up with a rapper/singer named Missy Elliott and making a few beats for her nascent R&B group Sista, he found himself part of a braintrust that Jodeci hitmaker DeVante Swing nurtured towards stardom. Tim’s early connects gave him a bit of leeway to learn and experiment under the aegis of a megahit crossover act, and his first breakthrough with Jodeci on Diary of a Mad Band deep cut “In the Meanwhile” reveals the then-21 Tim already deeply conversant in the kind of bass-heavy g-funk inflections that became a crucial transitional sound for R&B when new jack swing’s critical mass started to recede. And by the time Jodeci went on hiatus after The Show, the After Party, the Hotel in ’96, Tim and Missy had built up enough of a rep to weather it, relying on peers like Ginuwine and rising stars like Aaliyah who were eager to click with some of their more adventurous ideas. Since some of those more adventurous ideas — “Pony” and “If Your Girl Only Knew,” respectively — made high-number waves on the trans-Atlantic pop charts at the same time they perched atop the R&B singles ranks, that went a long way towards giving Tim, Missy and their clique enough clout to start really upending the conventional wisdom.

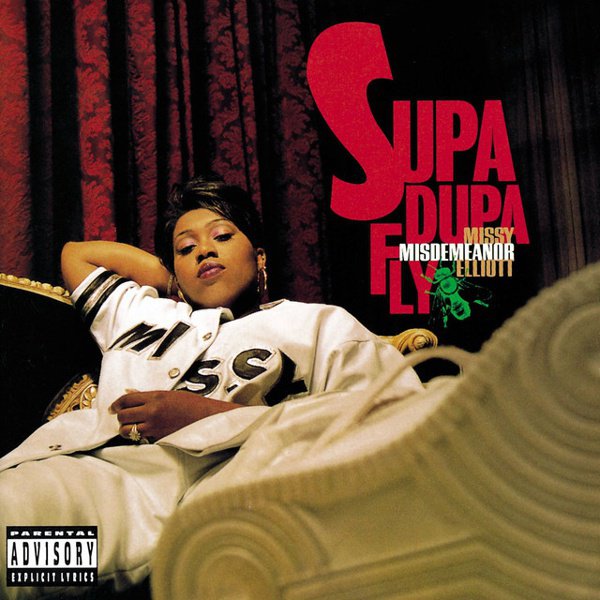

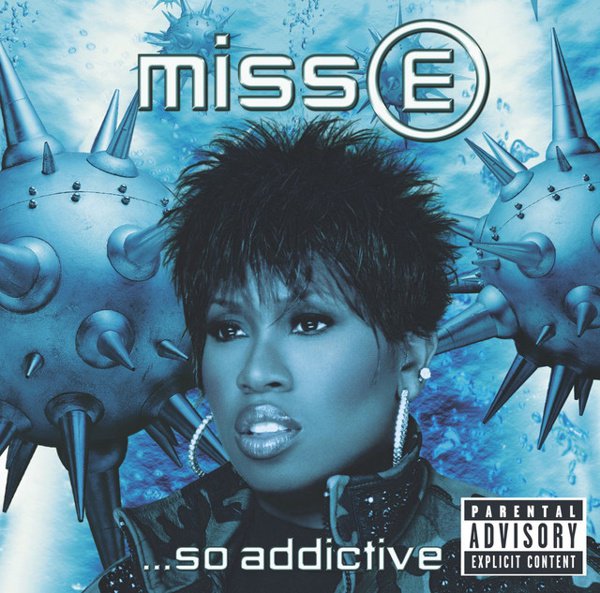

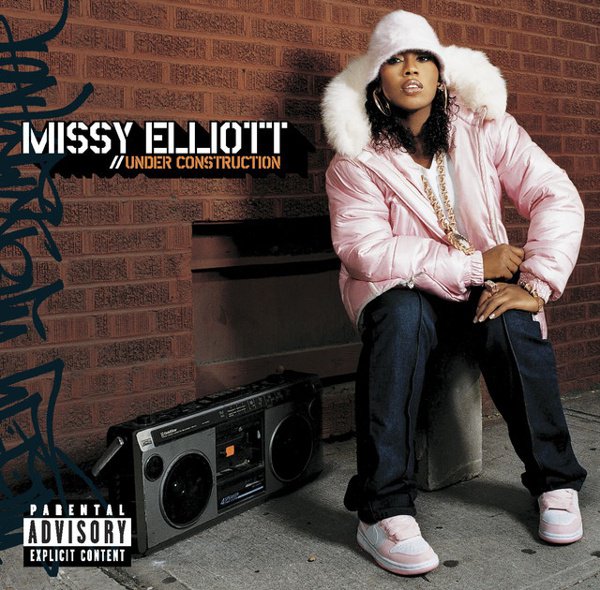

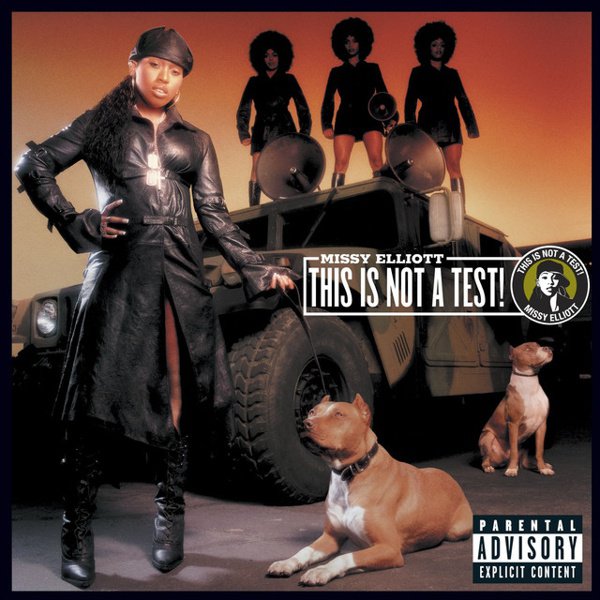

Most crucially, and a couple years or so ahead of his cousin Pharrell’s first big hits with the Neptunes, the conventional wisdom he challenged the most was the idea that hip-hop and R&B required disparate production styles. Granted, the South was already starting to prove you could make hip-hop without relying so heavily (or even all that much) on sampling, thanks in part to Organized Noize’s mid-’90s work with OutKast and Goodie Mob. And a couple years before that, Sean “Puffy” Combs executive-produced the debut album, What’s the 411?, that put Mary J. Blige in the position of embodying a hip-hop-driven strain of R&B. But Timbaland’s revelation — simple enough that it’s almost painfully obvious now — is that it’s all funk one way or another, and as long as you can get heads nodding and hips moving, everything else is up to the vocalist. Fatefully enough, when that vocalist was someone like Missy Elliott — equally conversant as a singer and a rapper, and deeply enthusiastic over the potential to hybridize those forms — it led to watersheds like debut Supa Dupa Fly and the four Timbaland-produced Missy albums which followed, which continually warped every traditionalist preconception of genrebound identity in ways that feel like a given now.

But Tim built from that already iconoclastic position to dig deeper: if you could erase the borders between hip-hop and R&B production, why not explore what they’re doing in the other clubs — including the ones that were bumping electronic dance music? If Timbaland wasn’t the first mainstream R&B/hip-hop hitmaker to really tap into the potential of techno, IDM, drum’n’bass, and the countless microgenres contained therein, he was at least the highest-profile one to treat that influence with an open mind and translate that into a major vibe shift. In the spirit of Hendrix psychedelicizing the blues and Stevie finding the soul in synthesizers, Tim made the idea of post-rave dance music sound like an influence that was both left-field and utterly integral. He’d dole that idea out sporadically across a few unlikely singles for a while, and while it might be a stretch to put ’98 joints like Jay-Z’s “Nigga What, Nigga Who (Originator 99)” or Aaliyah’s “Are You That Somebody” in the same stylistic ballpark as Aphex Twin or Roni Size, those uptempo rhythms’ controlled freneticism at least made it a lot easier to imagine a DJ set with close-proximity room for all of it. (Hell, Nicole Wray’s Tim-produced “Make It Hot” got sampled by the Chemical Brothers for “Music:Response” a year later — game recognize knob-twiddling game.) And once he expanded his horizons even further into international music — including the MENA and Indian sounds that Jay-Z’s “Big Pimpin’” and Missy Elliott’s “Get Ur Freak On” turned into global-village club jams — it was just further confirmation that hip-hop and R&B had become the renewed vanguard of pop-music creativity now that rock had hit its post-alternative creative doldrums.

A decade-plus after the ’96/’97 breakthrough that brought him to the upper echelon of superstar producers, Tim could have the ear of anyone he wanted or ever dreamed of working with. But somewhere along the line he lost the plot, overextending himself on eclectic pan-industry all-star hubris-displays like 2007’s Timbaland Presents Shock Value and ambitious but thin-stretched bids for further crossovers that ranged from diminishing returns (Nelly Furtado’s gem-laced yet deeply uneven Loose) to surprising letdowns (his character-deficient tracks for Björk’s Volta) to outright disasters (Chris Cornell’s omnidirectionally alienating pop-rock flail Scream). He’s been up-and-down ever since, and even if some of his later work has its moments, it’s arguable that he started to go astray with his late 2000s attempts to conquer pop on pop’s terms when he’d already done so on his. Maybe you can only sound like the future of everything for so long before you just want to bask in the relative knowability of the present moment.

Like many of his contemporaries, Timbaland’s identity was parceled out freely through singles and remixes, many of which capture his sensibility just as well as if not better than his album-length work does. (This playlist seems exhaustive — and at some points, exhausting — but every time you scroll, there’s a bunch of “oh, that one was a banger” revelations and reminders waiting for you.) And just like with the Neptunes, looking primarily at Timbaland through the majority-produced albums he did without fully accounting for his work outside them leaves the big picture incomplete while simultaneously illuminating how much inspiration and creativity his core group of collaborators instilled. That’s why this guide focuses on the handful of artists you could consider part of his inner circle. The one way that Timbaland’s music can really make you feel more nostalgic than future-shocked is by making you yearn for the sort of collective-effort unity that sprang from the core of artists he worked with from the ’90s onward — before we lost Aaliyah and Static Major, before Ginuwine strayed from the fold, before Missy went from regular welcome presence to behind-the-scenes hiatus. We had something special here — but fortunately, we can revisit it without feeling like we’re wallowing in an outdated aesthetic.