One of the oddest, and yet most exciting and musically fertile, stylistic fusions to occur in American popular music was Western swing – a blend of hot jazz, big band, old-time country, cowboy songs, and blues that emerged as a distinct genre in Texas and Oklahoma in the 1930s and came into full maturity over the course of the following decade.

Western swing has been largely overlooked in historical treatments of American popular music, in part because it’s still so hard to pigeonhole. The bands that played it dressed like cowboys but often had horn sections; they tended to be led by fiddlers, but their arrangements featured improvised solos that sounded a lot like big band jazz; they played traditional Appalachian old-time tunes that had their origins in the British Isles, but also Texas tunes that drew from German and Latin American melodic traditions. The music was White, but also Black; it was intensely American, but also more than a little bit Mexican. It was music deeply rooted in the rural Southwest, but refashioned to meet the demands of sophisticated urban audiences who wanted to dance to something that spoke to their country heritage while also packing a mighty sense of swing.

While regional bands like the East Texas Serenaders and Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel and his Hillbilly Boys were important innovators, Western swing really came into its own with the Light Crust Doughboys, a band that formed in Saginaw, Texas in 1931 and – amazingly – is still active as a working band today (with different members, obviously). The Doughboys were important not only as major contributors to the music’s early development, but also as the launching pad for the careers of two other vitally important figures in Western swing: Milton Brown and the legendary Bob Wills, leader of the Texas Playboys. But during the music’s heyday, there were scores of bands that developed regional followings both in the core hotspots of north Texas and Oklahoma and in outlying areas of Arkansas and as far east as Louisiana. Some of the first recorded uses of electrically amplified steel and six-string guitars were on Western swing recordings – an innovation made necessary by the large, crowded, and noisy dancehalls in which these early bands played.

Most of the early Western swing bands focused on live performance, and many made few if any formal recordings. Groups like Jimmy Revard’s Oklahoma Playboys, Adolph Hofner’s Texans, Bill Boyd & His Cowboy Ramblers, and the Tune Wranglers may have drawn big crowds in their prime, but virtually all of their work is now essentially lost to history – though some of it can still be found on labor-of-love compilations put together by diehard Western swing fans who have trawled patiently through collections of old 78 rpm shellac records to find obscure Western swing gems.

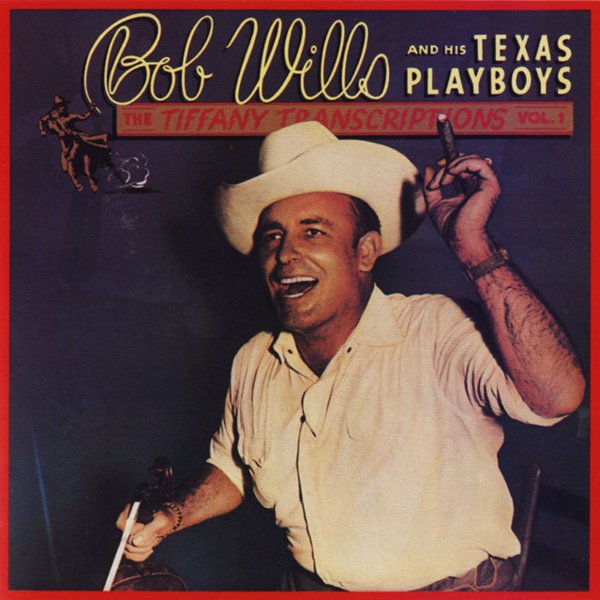

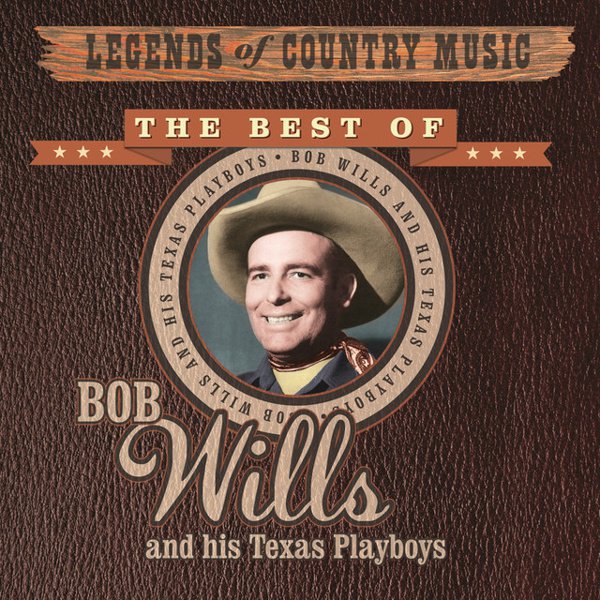

Today, Bob Wills remains the most recognizable name in Western swing – but that’s primarily because the career of Milton Brown and his band the Musical Brownies, who were for a time the more popular group, was cut tragically short by his death in a car accident in 1936. (Wills would later twice marry and twice divorce Brown’s widow.) During the ensuing years, Wills and his Texas Playboys went on to become international stars and the most popular exponents of Western swing. The combination of Wills’ virtuosic fiddling, the jazzy tightness of the Playboys’ horn section, and his playful call-and-response vocalisms alongside singer Tommy Duncan (punctuated by Wills’ signature falsetto “aa-haaaaaaaa”s) basically came to define the sound of classic, midcentury Western swing. Wills was a natural performer, an enormous stage presence who had done minstrel shows and musical comedy earlier in his career while supporting himself primarily as a barber. An irrepressible talker onstage, he developed a signature approach to performance that included not only between-song patter but also commentary during songs – often in the form of wordless vocalese, though he was also more than willing to interrupt and talk over his singers, pitching in vocal harmonies from time to time as well.

Wills was more than just a talented and charismatic showman, though. He was a tremendously gifted bandleader, and his success enabled him to attract major talent, most notably including singer Duncan, fiddler and electric mandolinist Tiny Moore, and steel guitarist Leon McAuliffe. And he was an excellent composer as well: his original tunes “San Antonio Rose” and “Faded Love” are now American jazz-country standards – while “Steel Guitar Rag,” an instrumental written by McAuliffe during his time with the Texas Playboys, is another.

Western swing hit hard times during World War II, when a 30% federal excise tax was levied on music venues (characterized as “cabarets”) that both served food and drink and allowed dancing. Some such venues tried to get around the tax by limiting its programming to performers who lip-synched and mimed along to prerecorded music; others featured live instrumental performances but did not permit their patrons to dance to them. This new era of nightlife regulation helped to hasten the evolution of jazz from dance music to concert music, ushering in the development of bebop (highly virtuosic, uptempo, small-group jazz intended for listening and virtually impossible to dance to) and leading quickly to the demise of big-band music generally. Western swing, which by this point had evolved into essentially a big-band genre, was collateral damage – although for another decade or so it continued to be popular as recorded music.

Western swing has never really died, however. Since World War II, Western swing has maintained a solid, if commercially modest, niche position in the musical marketplace. In the mid-1950s (after the cabaret tax was lifted), artists like Spade Cooley could still command large crowds, and the music’s enduring influence can be felt in the development of rockabilly music in the 1950s and in the Bakersfield Sound that emerged in Southern California not much later. In fact, Western swing was a formative influence on rock’n’roll generally: guitarist and bandleader Bill Haley, whose groundbreaking 1954 single “Rock Around the Clock” was one of the first commercially successful rock’n’roll recordings, actually got his start as a yodeling cowboy singer – and the band that came to be called Bill Haley & His Comets was originally called Bill Haley’s Four Aces of Western Swing.

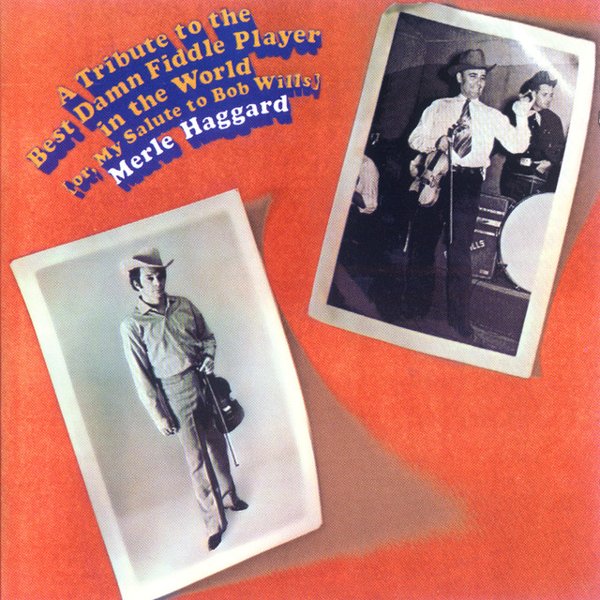

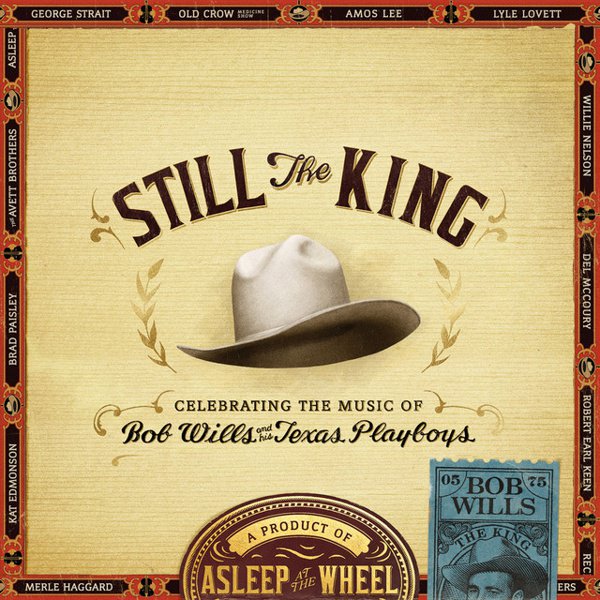

Country music made since the 1960s often contains strong hints of Western swing – you can hear it in the work of artists like Wynn Stewart, Dwight Yoakam and, especially, Merle Haggard (who recorded an album of Bob Wills covers titled A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddler in the World). Today you hear it in the music of California rockabilly artists like Big Sandy and his Fly-Rite Boys and of the minimalist, drumless trio the Hot Club of Cowtown. And most of all, you’ll hear it in the work of revivalists Asleep at the Wheel, who have been playing unashamedly straight-ahead, traditional Western swing (with significant commercial success) since 1970, as well as the similarly oriented (and more assertively named) Western Swing Authority. As recently as 2024, the town of Tehachapi, California hosted a festival dubbed the Western Swing Out, one that featured no fewer than 18 bands working in Western swing and adjacent styles. It’s a safe bet that Western swing is here to stay, though it seems unlikely ever to fully regain its prewar preeminence.